“Are not our generations the crucial ones? For we have changed the world. Are not our heightened times the important ones?...Are we not especially significant because our century is?...No, we are not and it is not. These times of ours are ordinary times...Who can bear to hear this, or who will consider it?"

The really interesting part is when we have lived long enough to bear hearing it, to consider it, to see just the tiniest flicker of the larger context, alongside the blinding subjectivity of our daily existence. We can begin to see that our lives, the surrounding cultures and subcultures that build, inspire, and support those lives are beautiful, essential, unknowable and fleeting. Somewhere in the mix comes this attempt to look back, to orient ourselves. Where are we? This strange year, this singular present moment, this contemporary time that occasionally seems so unfamiliar, so futuristic. And where were we before? This is not nostalgia, this is the most profound navigation, an attempt at narrative.

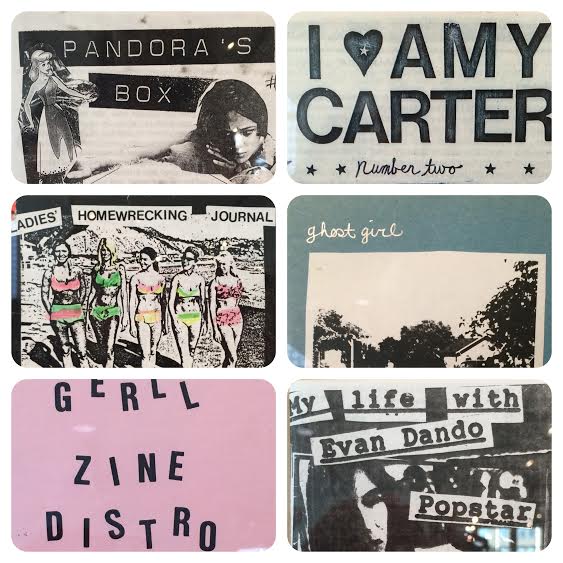

Last weekend, I saw ALIEN SHE at Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, an exhibit that examines the lasting impact of Riot Grrrl through archival ephemera, as well as a collection of contemporary works by artists who draw their influence from Riot Grrrl. What an intimate and unmoored feeling it is, at age 35, to see the counter-culture of my youth, these early ingredients of my very self on display with placards offering up dates and explanations. Aside from not being able to touch anything, the museum might well have been my high school bedroom. And, in many ways, Riot Grrrl was about our high school bedrooms, the stories written there, the music born there, the sensations of being a girl felt there, the tangible creative results that manifested.

As a teenager, I wrote BITCH on my stomach and went to a party wearing a beret and ripped up stockings. I can't imagine I fully understood the complex combinations of powerful and sexy this outfit inspired in me or why that mattered. But I marvel now at how lucky I was to have the images and language of this particular type of feminism available to me. That snarl and cuteness were ways we could be, an invitation to inhabit contradiction. "Dude, babe, sir," my sister and I joked, mimicking Kathleen Hanna's hilarious and deadpan railing against sexism in the music world on Mike Watt's Ball-Hog or Tugboat album. It would be a long time before I'd hear the phrase third wave feminism or even begin to comprehend why, as an adult woman, I'd wear fuchsia stockings to work and keep my last name when I got married.

With a spate of films, books, archives, documentaries and exhibits, Riot Grrrl is getting examined and celebrated. Something so visceral cannot yet be a documentary-tidy closed case, right? The past still reverberates, is still relevant. Riot Grrrl politics still have a place; evolved or updated, but still...connected. Watching The Punk Singer, I nearly cried when Kathleen Hanna says she doesn't care if people believe feminism is still important or not, because she knows it is. 'Girls to the front,' was her rallying cry at the rowdy shows Bikini Kill used to play. She no longer says this because girls are at the front. Yet, too, as Sarah Marcus, author of Girls to the Front, says in the New York Times, “people are flocking to these reminiscences because there remains a tremendous hunger.”

Perhaps hunger is a better word than nostalgia. We seek to understand something while it's happening, and again when we believe it's over, more confident in our abilities to take stock. Yet a different sort of complexity is born when we attempt to weigh the retrospective. Looking back is so evocative, muddled with confusion, recognition, some stirring, some realization of how small we are even in our most important moments.

Still, the moments matter because they matter to us. The larger cultural realities help us with our autobiographies, and so are sometimes too difficult to stay objective about, and why should we? Like anthropologists, we might pick up and turn over the reasons for who we are. I wandered the Riot Grrrl exhibit, the fragments of it like a memory in 3D, vivid and fractured, sweet and illuminating to recall, but also not entirely finished or clear.