Last week I found $40 in an ATM, the gift of a forgetful person with over $7,000 in their bank account. Despite myself, I felt compelled to return it, though I sort of felt like I could use it more than them. The bank manager and security guard were aghast and confused, before finally declaring me the kindest person ever, with good karma coming my way, and a future payday of even greater magnitude from God himself. It made me want to do unexpectedly nice things more often. But more than that, it got me thinking about money and what it means. I pictured panning for gold in rivers and bartering with cows. I pictured our current little pieces of blue plastic that let us spend more than we even have. How bizarre it all is!

Money shapes our every perception. It ends our marriages, determines our happiness, populates our pop and hip-hop songs, confuses our desires and weighs us down in both its lack and excess. After returning the $40, I was slightly surprised to find that not having it made me somehow grateful, actually lighter. I thought of Walt Whitman’s lines, “despise riches…devote your labor and income to others…dismiss whatever insults your own soul.” It sort of felt like I'd done that for a moment and the feeling made me want to do it more.

Money is somehow both an abstraction and a tangible object. From gold to cowrie shells, to deerskin leather with colorful borders, money is an idea to which humans attach value. Coins with numbers and presidential profiles pressed in relief onto metal, paper with pyramids drawn in green, money is a political, private, convoluted entity. For something we aren’t supposed to discuss if we're being polite, we’re talking about money constantly; in poetry, in hip-hop, on reality television, in the news, in psychology, in advertising, in art, in our relationships…and what is it we’re really saying? Is it possible to decode?

In Miranda July’s first piece from her We Think Alone project, the celebrity emails all reference money. My favorite is the writer Sheila Heti’s letter, which discusses the specific amount in her bank account (a charming rejection of a social no-no) as well as her lack of skill with money and plan to pitch articles to women’s magazines for extra income. Meanwhile, she’s a successful author with multiple books, still scheming and scraping by this way. Henry Miller’s essay "Money and How it Gets That Way" inspired this article and responds to a question from Ezra Pound asking Miller if he ever thinks about money. He did apparently (and writes intriguingly and often about borrowing and lending it). His essay is a meditation on the strange, un-pin-down-able nature of money. Page after slightly-confusing page, discusses ancient histories, tautologies, and “the mystic presence” of gold. I love his essay because it treats money like the oddity it is, something to be scrutinized in a microcosmic, bemused, surrealistic fashion, rather than viewing it as the commonplace phenomenon we usually do.

Recently, one of my high school students, in response to a writing prompt, simply wrote, “I heart $.” “Why?” I asked, not yet getting into the issue of a heart and dollar sign substituting for actual words. She wasn’t sure. She thought she wanted the things the $ would get her, but struggled to even list what those things were. More often than not, my students say they want to be rich before they say what it is they want to do exactly in order to get that way. It's an interesting, disturbing assumption that after riches comes everything else one might want or need, yet I obviously understand why they feel that way, and sometimes agree. Granted, we need money to live. Often more of it than we can seem to earn or keep. There are, of course, the larger issues of our current collective financial conditions; the social and political realities of capitalism, the devastation of poverty, the recent hoopla over the 1%, the infuriating banking systems and distribution of wealth. But that's overwhelming. When I consider all of this, I want to go very small, very micro. In going to the deeply personal, I can begin to think about these ideas at all.

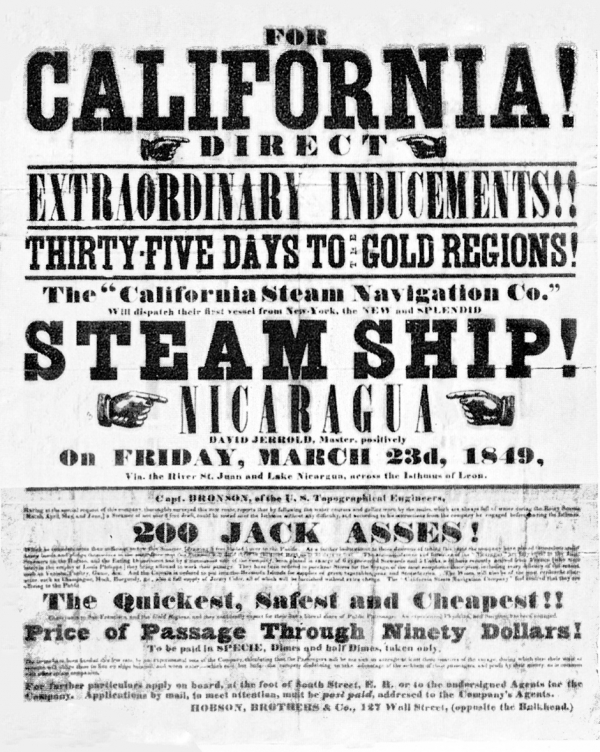

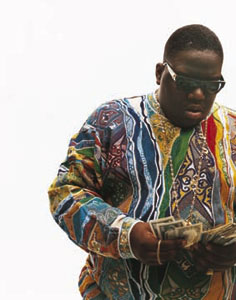

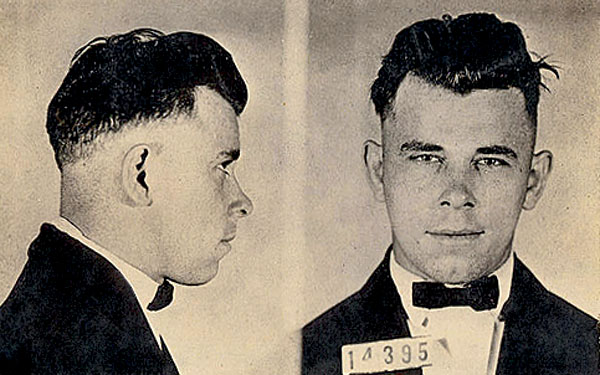

I’m curious about the individual, private world of money and how it's then represented and discussed in our popular culture. What of those quiet, concealed moments that form our relationship with money? We grew up watching our parents save, spend, or struggle, pass down wisdom or lack thereof, in overt and subconscious ways. But then what happens as media reflects and distorts these notions of money back at us? We're riveted by rich people and celebrities, by royalty and luxury. We have the old school gems of Pretty Woman and Trading Places. The current horrors of the Kardashians and Real Housewives, the impossible wealth of Gossip Girl, and even ostensibly well-meaning shows like Separated At Birth depict class in incredibly problematic ways where the comforts of being rich look appealing beyond all else. There's Kate Middleton, whose outfits (along with their price tags) and baby we can't get enough of. Girls who are famous simply for being rich or the children of the rich. There's our mythological attraction to the outlaw bank robber, to John Dillinger and Bonnie and Clyde. We're never sorry the bank got robbed. There's Pretty in Pink (and a zillion other wrong side of the tracks/right side of the tracks love stories). Frank O’Hara. Biggie. Madonna. Wordsworth who says, “The world is too much with us; late and soon/ Getting and spending, we lay waste our powers.” Rihanna who says, "All I see is dollar signs/Ohh/Money on my mind." This constant and conflicting narrative intrigues, yet seems to pose more questions than it answers, offers far more concerns than comforts.

Money can’t buy happiness, we’re told, and yet so often it seems that it might. Studies have been done that find those who make over $50,000 a year actually are happier, a statistic that isn’t really surprising. Often it's precisely a lack of money that's the cause of myriad unhappinesses and suffering. Money, in certain terms, is obviously a quantitative measurement of success and stability, one it's OK and even important to seek. “What other measurements of success are there?” someone asked me recently. We were discussing the qualitative virtues of a "starving artist" life, one full of Kickstarter campaigns, no health insurance and freelance writing jobs. We discussed the ephemera of creativity, inspiration, connection, goals that don't necessarily have monetary outcomes attached. After all, famous writers still have teaching jobs. More than one local musician works at Tartine. People who write successful screenplays need help from their friends to get to Cannes. These aren't sad stories by any means, yet they complicate our ideas of what success or money even really means. I was in Reno recently, watching as people gambled away what could only be millions of dollars around me. There were those having fun, irreverent, dressed in gold and sequins, laughing. There were those leaned over the tables with intention. Some people were winning money, others losing it. Regardless, the clinks and clanks of the machines suggested winnings were pouring in. In the grand scheme of things, they weren't. Henry Miller ends his essay with the simple thought that those with cash on hand in the end will be the best off, and he's right, but he's also being scathing. Money has no life of its own except as money, he writes. It's an uneasy thing, our private battles and ideas of money, and they manifest everywhere in the strangest ways. It stands to reason we're obsessed. There's no easy conclusion and there's little to comfort ourselves with.