The Family Business: A Tale of Internment and Persistence

The Family Business: A Tale of Internment and Persistence

M

aya Shiroyama and her husband drive down Interstate 880 in their dark gray Prius. They're on their way to San Jose. Usually the roads are flooded with traffic, but on this day it is clear.

They pull up to a ranch-style tract home and park in front. As they walk up the driveway, an older man eagerly swings the front door open.

“Hi, I’m Maya,” she says. "Nice to meet you!"

The older man reaches out his hand toward her, “Hi, I’m Tom.”

Tom Kitazawa is 87 years old and the last surviving son of the founder of Kitazawa Seed Co., a business that opened its doors 100 years ago.

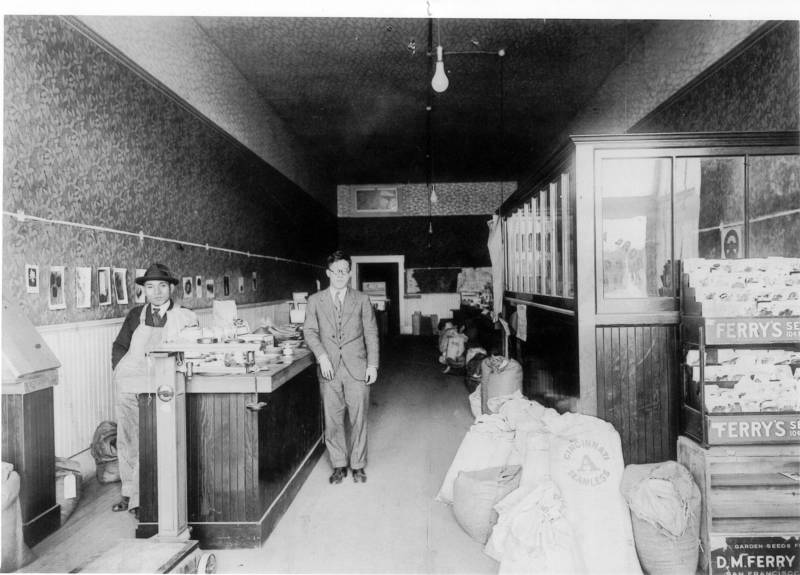

Tom’s father, Gijiu, was a Japanese immigrant who sold vegetable seeds to Japanese-Americans hungry for the taste of home -- favorites like Japanese eggplant, shiso leaves and daikon.

But the seed company almost went under several times. First, the Kitazawas were locked up in an internment camp during World War II. Gijiu had to rebuild the business from the ground up after the war ended.

Then decades later, another Japanese-American family -- Maya and her husband -- saved the business. But the two families never had a chance to sit down and share stories of how the company tied them together.

B

efore World War II, two-thirds of Japanese-Americans worked in agriculture and related businesses like wholesaling, transporting and selling of food. The war would change all that.

In February 1942, two months after Japan bombed Pearl Harbor, President Franklin D. Roosevelt ordered the forced relocation of more than 100,000 Japanese-Americans.

Tom, then a young boy, remembers leaving San Jose for the camps. His dad had to sell all his seed stock because the family didn’t know when or if they were coming back.

“People had to get rid of everything in their homes. Because they could only take what they could carry," Tom tells Maya.

He looks down for a moment as he reflects on the journey to Heart Mountain, a camp in Wyoming.

“You know we were all being brought to the railroad tracks. Not to the railroad station, but the railroad tracks,” he says.

Then the family was shoved into a boxcar and rode in it for several days to get to the internment camp.

After Heart Mountain, the Kitazawas eventually found their way back to San Jose. Gijiu, Tom’s dad, tirelessly worked to reopen the business.

“He immediately started doing those kinds of things that he felt needed to be done so far as reviving the seed business," Tom says. "He made contacts with the seed companies and his suppliers,”

M

aya was born about a decade after the war and grew up outside Fresno, where both sets of her grandparents had farms. Her grandparents were sent to internment camps, too, but returned and resumed farming.

“Both families were fortunate to go back to it," she tells Tom. "Their neighbors took care of it. So Kitazawa is how I learned how to garden.”

But she didn't know that the seeds she planted would one day connect her family with Tom’s.

That didn't happen until 1999, when Maya's father told her that he hadn’t received his regular delivery of Kitazawa seeds. He asked her to drive from her home in Oakland to San Jose to find out why. The seeds hadn't been shipped, she discovered, because the business was struggling.

Tom’s father died in 1963. The business was passed through the hands of various family members and eventually ended up being run by Tom’s sister, Helen. But Helen's husband had died, and she was having trouble running it without him. (Tom had a full-time career as a computer programmer and wasn’t interested in taking over the seed company.)

“I asked her about what would happen to the business, and she says, 'Well, we’re going to close the doors.'” Maya tells Tom. “I told her that’s a huge shame because Kitazawa Seed Co. is just a huge part of Japanese-American history.”

She bought the company in 2000 and moved it to Oakland. Kitazawa now has an online store and offers seeds for hundreds of varieties of vegetables from Japan and other parts of Asia.

While Kitazawa Seed Co. has been modernized, some things have stayed the same -- like the seed packets, which are small manila envelopes with green ink.

Tom tells Maya that he remembers having to scoop seeds into the seed packets with a metal spoon. She laughs and turns to him and says, “Tom, it hasn't changed much today!”

Maya and Tom soon realize they have been talking for more than two hours. They're hungry. They talk about getting lunch in San Jose's Japantown.

But before they get up to leave, Tom looks down and begins to slowly speak.

"There were so many Japanese families that had to go through a very similar kind of thing," he says. "Regardless of the hardships, we were very lucky."

Then he reminds Maya that he’d love a seed catalog to give his grandchildren -- so they, too, will know their own history and pass it along to future generations.