In recent weeks, Floyd has taken huge steps to improve from what was a disastrous first semester of high school, when Floyd would skip school for days or even weeks at a time. His grades last semester were even worse.

Still, Floyd -- who says he's hoped to attend college since he was 8 years old -- knows his current grades aren't guaranteed to get him there. At University of California or California State University campuses, students need at least C's to qualify for admission.

And University of Oregon education professor David Conley, who has studied the transition from high school to college since the 1990s, says decent grades and regular attendance are only preliminary steps toward higher education. It's the next steps that are often the hardest for ninth graders, especially for low-income students or students of color. (Most students at Floyd's school receive free or reduced lunch; practically all are Asian or Latino.)

Conley says, in surveys, between 80 and 90 percent of entering ninth graders report hoping to achieve at least a bachelors degree.

By the time they graduate, students from middle- and upper-middle-class backgrounds tend to report even higher aspirations: "In other words, by the end of high school they don’t just want to go to college, they want to go to grad school," Conley says.

Low-income students and students from underrepresented minority groups report the opposite trend.

"Over the four years of high school, their aspirations go down. By the end of high school, they’re talking about maybe community college or just going to work or going into the military. So you’ve got this divergence of aspirations occurring over a four-year period."

The difference has to do with all the next steps Floyd will have to complete in order to get to college: figuring out why he wants to attend college and what he wants to study, finding the right school to attend, arranging financial aid and perhaps taking an entrance exam like the SAT or ACT.

But economically privileged students tend to have adult help and life experience necessary to tackle those challenges. Less-privileged students, Conley says, tend to get less help, leaving some discouraged or unsure of how to pay for college.

But Floyd says he's ready to do "what he's gotta do," as he puts it, to get his grades up and get to college.

"I've been tired of being in trouble -- getting bad grades and stuff like that," says Floyd. "It's like God just talked to me, touched me, or something -- just told me to go to school."

Football Helps With Focus

Floyd's college aspirations are rooted in one desire: to play professional football.

"Football's my life," he says. "It’s something I want to do for the rest of my life."

"He’s wanted to play football ever since he was a kid in elementary school," says John Maxey, Floyd's father.

Back in his early years, Floyd dreamed of donning pads for the University of Southern California. Now he dreams of playing for other schools with storied football programs: the University of Oregon or Clemson University, in South Carolina.

Floyd played on Locke's junior varsity football team last year, and hopes to make the varsity squad next year. "I think it focuses him," his father says.

On some level, Floyd has always known playing college football would require actually getting into college. But when he entered high school, daunted by harder classes, he decided to start "ditching" school.

"Right there, I was, like, forget school," Floyd says, explaining his thinking. "Forget college and stuff. Like, I can’t do this no more. I can’t be nobody that I’m not. I’m not that type of person. School’s just not for me."

Floyd says it wasn't just the difficulty of the courses that prompted him to miss so much school. People in his neighborhood, just west of the 110 Freeway from Watts, would cajole him into skipping school.

Meanwhile, John Maxey, who's 79 years old and retired, began to notice the absences piling up. Floyd offered his excuses, but John would get on his son's case about hanging out with people he felt would lead Floyd astray.

Finally, on a day Floyd was skipping class, his father saw Floyd walking down the street going to get something to eat.

"My dad saw me in his car," Floyd says, "and I was like, like, 'Dang, I really got caught.'"

"I told him to get his butt out of there and get to school," his father remembers.

Floyd says, in that moment, something clicked.

"I want my dad to be proud of me," he says. "I want to be like my sister and go to college."

From 'Focus List' to Turnaround

City Year's assessments had identified Floyd as a candidate for extra help months before he was ready to accept it.

Floyd's sporadic attendance, tendency to goof off in class and his academic performance in core subjects like reading and math landed him on what's known as the "focus list." That designation means that, while Floyd wasn't severely off-track during his first semester, he was still far enough behind in school that he required extra attention. (City Year believes students with high levels of need require the instruction of credentialed educators.)

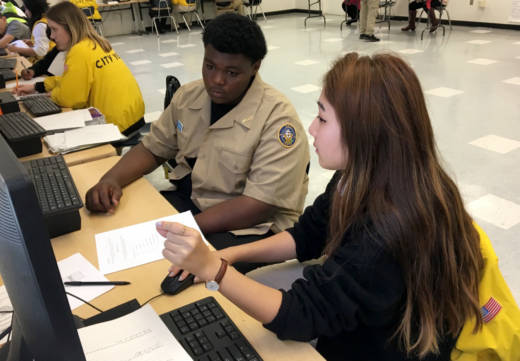

Eleanor Kim is one of 288 AmeriCorps members working in 28 L.A. schools through City Year. In the fall, mentors like Kim selected between eight and 12 "focus list" students with whom they'd work closely throughout the year. Across L.A. this year, City Year volunteers are helping more than 2,800 "focus list" students and interacting with more than 12,000 students in classrooms or after school programs.

Kim says Floyd's math teacher initially suggested she take him on as a mentee -- but like his teachers, Kim didn't see much of him during his first semester. Like Floyd's father, she too found him once on the sidewalks near the school at a time he should've been in class.

But Kim says she sees Floyd much more often -- not only in the literacy class where she works with him daily, but in City Year's after school tutoring program.

At their report card conference, Kim asks why Floyd is having such a hard time focusing in math.

"I always talk" with friends in the class, Floyd says -- an unhelpful distraction, he admits. "And then the work be hard, so I don’t got nothing to do but talk."

This was a main reason why Floyd began skipping school in the first place -- he folded when classes got hard. Eleanor pushes him to tough it out.

"You’re going to make a commitment to improve," Kim tells him.

But before she concludes, she adds some good news. Floyd may still have D's, but in several classes, his grade is so close to a C that he could likely improve by asking teachers about making up missing assignments or retaking tests he'd flunked.

"Those are so close to a C," Kim says, surveying his report card.

John Maxey says he still feels Floyd has a long way to go. If he had to grade his son's current effort to improve his performance in school, Maxey says he'd give Floyd a D. He's still concerned about the company Floyd keeps outside of school.

"If he doesn't change, he's not going to make it" to college, Maxey says.

Overall, Kim, a UCLA graduate who hopes to attend medical school next year, says she's impressed by Floyd's turnaround so far -- and has high hopes.

“In my mind, I’m convinced he’s going to graduate from high school," Kim says. "I want him to have that same kind of mentality and mindset.