She decided to call a lender whose advertisements she'd heard on the radio and apply for a $1,000 loan. The company's representative told Davis that she qualified for more than double that amount.

"I was like 'wow!' I was excited, so I went for it," said Davis, adding that the extra funds would be handy to catch up on utility bills and rent. She clicked through the contract online, with the representative speaking with her via phone.

Later, Davis realized her $2,600 loan had an annual interest rate of 200 percent. If she completed the four-year repayment plan, she would have paid about $20,000.

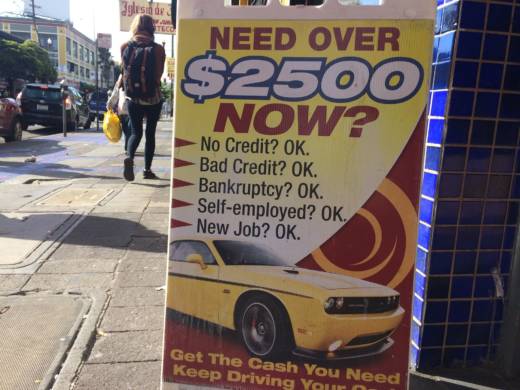

California limits interest rates for consumer loans under $2,500. But larger loans, like the one that Davis got, have no such limits.

Assemblyman Ash Kalra (D-San Jose) wants to put interest rate restrictions on bigger loans as well. His AB 1109 would limit the annual interest rate to 24 percent on loans between $2,500 and $10,000.

Kalra said the intent of his bill is to protect low-income families who end up getting this type of financing to cover an immediate expense, like car repairs or hospital bills.

"Families are already going through crisis when they come forward asking for these loans," said Kalra, a former City Council member who pushed for greater regulation of payday lenders in San Jose.

"We should not allow for an additional crisis to be placed upon these families by putting them on a downward spiral of debt," he said.

In 2014, when Davis signed up for her loan, non-bank companies provided more than 250,000 loans to consumers with interest rates of 100 percent or higher, according to figures by the California Department of Business Oversight. That number jumped to nearly 330,000 in 2015.

The California Financial Service Providers Association, which represents businesses that offer consumer loans and check cashing, argues that their industry provides important access to credit.

"We believe all California consumers, particularly those in underbanked communities or stuck in a credit gap, should have maximum flexibility to make their own choices and enjoy access to a broad and responsible range of financial services," Thomas Leonard, executive director of the California Financial Service Providers Association, wrote in a statement.

The association does not represent LoanMe Inc., the Southern California-based company that originated Connie Davis' loan.

LoanMe representatives did not return phone calls and emails requesting comment. But non-bank lenders have argued that flexible interest rates are necessary because borrowers' credit ratings are low and default rates are high.

"Arbitrary interest rate caps like the one proposed harm those who already have the hardest time accessing credit," said Lisa McGreevy, president of the Online Lenders Alliance, a national trade association.

Juliana Fredman, an attorney at Bay Area Legal Aid, represents low-income consumers on debt collection cases. She said typically her clients, like Davis, don't fully understand the terms of the loans they signed up for and can't keep up with payments.

"There’s a lot of stress and a lot of shame, and also concrete issues around credit which can impact housing and their ability to get loans at a more reasonable rate," said Fredman, a professor at UC Hastings School of Law.

For Connie Davis, the experience has been so embarrassing she hasn't discussed it with family and friends.

"I was blindsided," said Davis, whose credit score took a further hit after she was unable to pay her rent and keep up with the loan's monthly payments of over $400. "If I knew upfront that I would be paying a total of $20,000, I wouldn’t have signed that paper."

A class-action lawsuit against another lender, CashCall Inc., is currently making its way through the U.S. 9th Circuit Court of Appeals in San Francisco. The plaintiffs allege that CashCall's loans of $2,600, with interest rates between 96 percent to 135 percent, are "unconscionable," said Steven Tindall, one of the attorneys in the case.