"They’re going to give him a general anesthesia, like people do every day for major operative procedures," Riggins tells me. "He just isn’t going to wake up. He is going to die in his sleep. So cruel and unusual punishment? Not really."

On my visit to death row late last year, Richard Hirschfield, the man who killed John Riggins and his girlfriend, told me he wasn't too concerned about getting an execution date.

"I’m not too concerned about it because I really don’t think that I’m going to be killed," Hirschfield said through the bars on his prison cell.

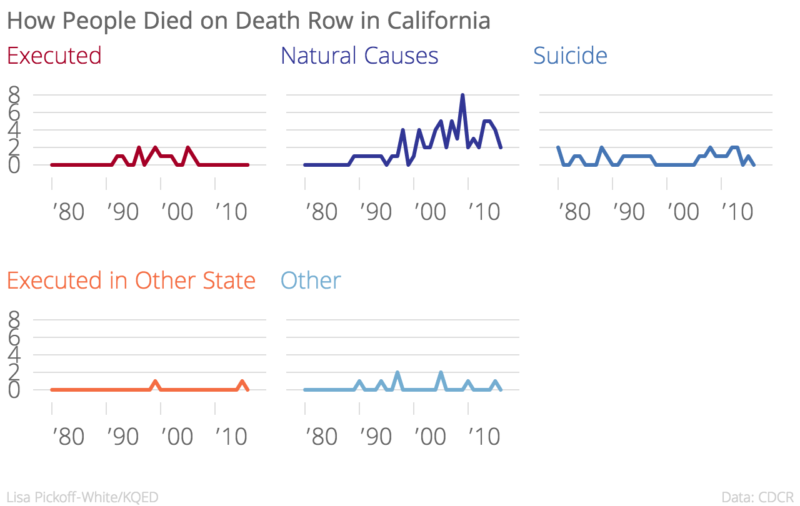

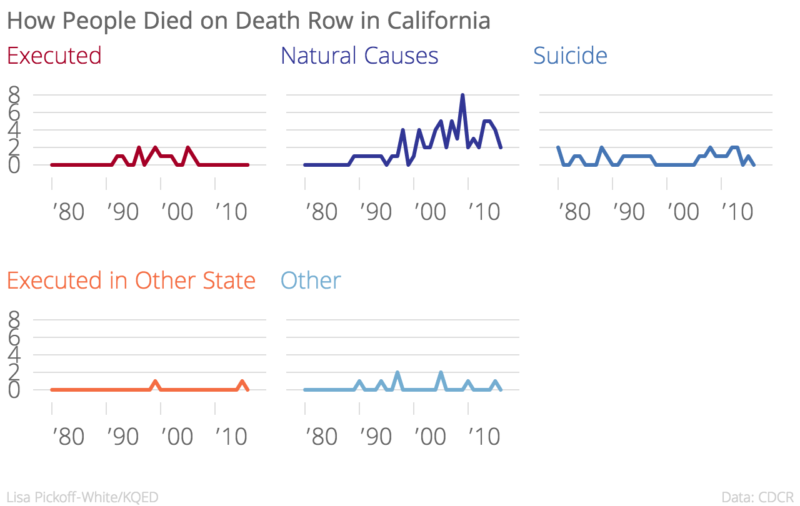

Hirschfield has good reason to think that. Since California reinstated the death penalty in 1978, nearly 900 death sentences have been handed down by juries. And yet the state has executed just 13 condemned inmates. The last was Clarence Ray Allen in January 2006. Later that year, federal Judge Jeremy Fogel suspended executions until the state revises the protocol it uses to put inmates to death. There hasn't been an execution since then.

Even before Fogel stopped executions, legal appeals for death row inmates dragged on for 20 years or more. With that in mind, backers of Proposition 66 are seeking to reduce the time between a death sentence being handed down and carried out.

Proposition 66 seeks to "mend, not end" the death penalty so that decades-long delays are eliminated.

It would do that by changing the procedures governing legal appeals, which are automatic in California. It would also require more attorneys to accept death penalty appeals cases and train them in how to handle those cases. And it would shorten the amount of time allowed for state appeals and require death row inmates to work while in prison and pay restitution to their victims.

"It's unconscionable that it should take 25 to 30 years, and that individuals are dying on death row of natural causes, when a jury has said that this (death) is an appropriate sentence for very rare circumstances," says Sacramento District Attorney Anne Marie Schubert. She thinks Proposition 66 will help deliver more timely justice to crime victims.

Of course not everyone agrees.

"That initiative is a false promise of expediting death sentences," says Santa Clara University Law School professor Ellen Kreitzberg. She supports Proposition 62, a competing measure to end the death penalty.

"The danger with Proposition 66," she says, "is it does limit and narrow the ability to present newly discovered evidence, which is how most of these innocence claims are presented in court."

She and other critics of Proposition 66 think speeding up the appeals process could lead to a catastrophic mistake in California -- like executing an innocent person.

The weak link in Proposition 66 might be funding it. The measure contains no language requiring the state Legislature to spend the money on training additional attorneys to handle death penalty appeals.

San Mateo District Attorney Steve Wagstaffe, president of the California District Attorneys Association, admits that getting Proposition 66 funded could be problematic, especially with a governor and state Legislature opposed to capital punishment.

"We recognize it’s going to have to rely on the Legislature implementing the will of the people" Wagstaffe says. "And if they do not, well, that is on them."

This story is part of our California Counts collaboration with four California public media organizations to cover the 2016 election. The partners include KPCC in Los Angeles, KQED in San Francisco, Capital Public Radio in Sacramento and KPBS in San Diego.