“That’s part of the magic here,” Chellam says. “We’re not going to order from anybody. We’re going to order from computers.”

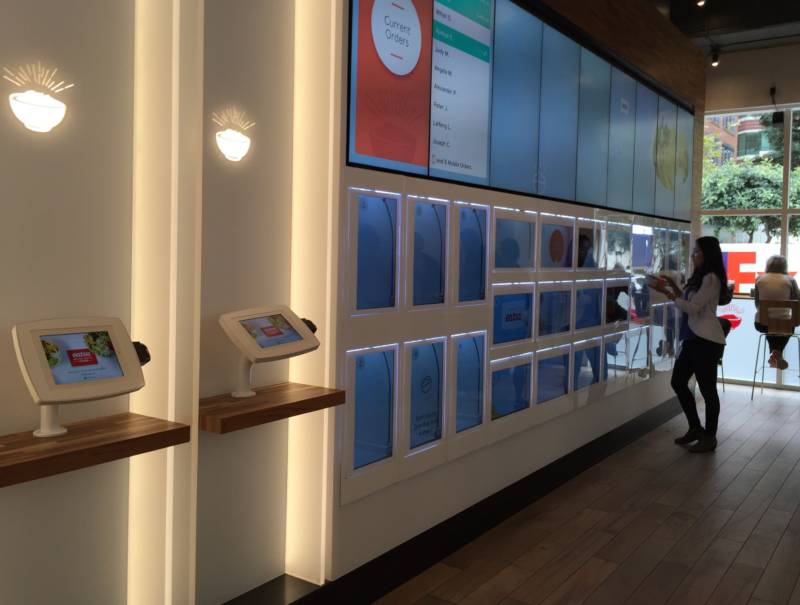

Chellam and I walk up to one of the iPads mounted on the wall. The first step is to swipe your credit card, which Chellam does.

“Now what are we going to eat?” Chellam asks after his credit card is accepted.

Eatsa’s thing is quinoa bowls, and you can see photos of its offerings on the screen. I go for the burrito quinoa bowl and Chellam orders the kale.

“Yeah, I’m in San Francisco. I feel like I need to do with kale,” he says. “But oh, I don’t want that cheese.”

A couple of clicks later and we’re done. The process is pretty simple and intuitive if you know your way around an iPad. When our food is ready, it appears in one of the cubbyholes lining a wall of the restaurant. Each cubby has a translucent blue cover, and when your name appears on it, that means your order is up. Our food pops up in cubbyhole No. 3.

There are about 15 to 20 customers in here the day I visit, mostly young tech workers from the neighborhood. I see just one eatsa employee in the restaurant.

“I have this gut sense from having been in the valley for a while now that there will be a coming wave of automation that will get rid of a lot of jobs,” Chellam says, back at his office in downtown San Francisco.

It's unclear whether technology will eventually reduce the total number of jobs in the country. While technological advances make some jobs obsolete, the past has shown that tech has also created new opportunities.

But advancements in artificial intelligence are intensifying this debate. In Silicon Valley, there are lots of experiments in automation. There's the robot at Lowe’s home improvement store in Sunnyvale that checks inventory. There’s the “robot butler” working at a hotel in Cupertino. And then there’s Uber, which is experimenting with driverless taxis and trucking.

“And that affects 3.5 million truck drivers, another 5 million people who service the truck-driving industry, and then all the towns and services that support trucking routes,” Chellam says. “And that’s just one example of automation.”

Chellam says software is eating white-collar jobs, too, and everyone from bookkeepers to doctors and lawyers will be affected.

Chellam criticizes politicians for not talking about this automated future. At best, he says, they talk about “retraining,” which doesn’t address the scope of the problem.

“Take the truck driver example,” he says. “What are you going to retrain 3.5 million people to do in a short enough period of time when whatever you’ve retrained them to do isn’t automated itself?”

A future in which technology eliminates human jobs is raising an alarm among some experts. But Chellam is part of a small cohort of tech entrepreneurs in the valley who think there could be a solution: The government could give people “cash” to help pay for those basic needs.

“It seems like we need to do something to lessen the blow, and I think basic income could be a good solution,” Chellam says.

Silicon Valley’s interest in the universal basic income is one part guilt and one part optimism, says Natalie Foster, a fellow at the Institute for the Future, a nonprofit research organization in downtown Palo Alto.

“This is a community that likes big moonshot ideas,” Foster says.

Some technologists suggest setting the basic income at $10,000 a year. Others have proposed raising carbon emission taxes to pay for it. Foster says there hasn’t been enough research on basic income to have serious policy discussions. She says that right now tech workers are in the “inquiry and research phase.”

They’re holding meetups and hosting panels asking what would it mean to give people money they didn’t work for, Foster says.

In Oakland, they’re about to find out. Y Combinator is funding a research project on basic income, where it will pay 100 people enough money for food and shelter -- no strings attached.

The prestigious tech accelerator helped launch companies like Airbnb and Reddit.

Y Combinator declined requests for an interview, but in a blog post its president, Sam Altman, stated that at some point in the future, as technology continues to eliminate traditional jobs, some version of basic income will be rolled out nationally.

The debate about whether machines are taking our jobs is beside the point, says Chris Hughes. He’s a co-founder of Facebook and active in the basic income movement. He says the reality is that work has already changed.

“You know 40 percent of jobs are now contingent, meaning they’re part-time, independent contractors, Uber drivers,” he says.

And he says that shift has left middle-class Americans economically insecure. In May, the Federal Reserve released a study that said 46 percent of Americans surveyed didn’t have enough cash to cover a $400 emergency expense. That feeling of insecurity is evident in this tumultuous presidential election.

“I think there is a sense that our economy is broken,” Hughes says. “Rather than try to restructure our economy so it looks like the 1950s, I think we have to be honest with ourselves.”

Hughes says that means basic income isn’t an idea for the distant future but one we need to consider today.