The process by which initiatives become California law has remained mostly unchanged for more than a century, but it has not been completely sacrosanct. Some of the rules have evolved, and one big factor in the process changes every four years: the threshold for an initiative to actually get on the ballot. (But more on that in a moment.)

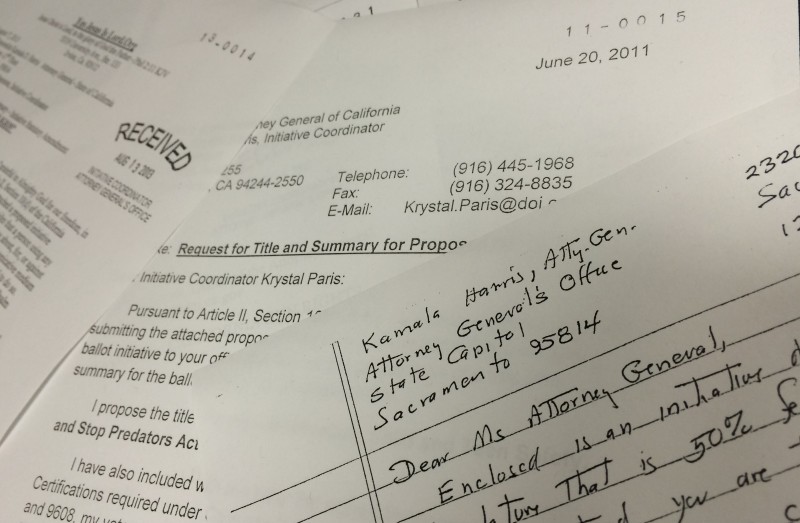

Still, politicians and citizen groups alike have generally hewed to the notion that the 1911 state constitutional amendment forbids too much tinkering. Which brings us to the growing outrage over an initiative submitted for consideration on Feb. 26 by a Huntington Beach attorney.

Simply put, his proposed law is shocking, laid out in just 43 words:

"The People of California wisely command, in the fear of God, that any person who willingly touches another person of the same gender for purposes of sexual gratification be put to death by bullets to the head or by any other convenient method."

Those words have become the subject of intense scrutiny, both in state and national media.

But the author of the self-proclaimed "Sodomite Suppression Act," Matt McLaughlin, has gone radio silent when reporters have tried to contact him for comment. Other than the fact that he's been a licensed attorney for 16 years and professed the impact of the Bible on his life in a 2004 newspaper story (about another unusual initiative he had written), McLaughlin is pretty much a mystery.

But the author of the self-proclaimed "Sodomite Suppression Act," Matt McLaughlin, has gone radio silent when reporters have tried to contact him for comment. Other than the fact that he's been a licensed attorney for 16 years and professed the impact of the Bible on his life in a 2004 newspaper story (about another unusual initiative he had written), McLaughlin is pretty much a mystery.

Even so, an intense effort is now underway to have him disbarred, while groups across the political spectrum have criticized or condemned his proposal. And as we discussed on last week's California Politics Podcast, there's certainly the potential that the more oxygen the story gets, the more brightly the flame burns on promoting an extremist point of view.

Change The System? If So, How?

But the better question may be whether there's anything that it should spark in the way of changes to California's initiative process. There have been nips and tucks made over the years, but the fundamentals have remained pretty constant: drafting the proposed law, even if it's in your own handwriting; handing over $200 to the state attorney general's office; and then gathering the signatures of voters.

It's not easy to clear that last hurdle. Since January 2012, there have been 105 proposed initiatives submitted for a formal title and summary, but only 16 that have made it to the ballot.

Though some have demanded otherwise when it comes to McLaughlin's anti-gay proposal, there's nothing in the law that gives state Attorney General Kamala Harris the power to block a measure she -- or anyone -- deems a mistake. If anything, the clamor over the years has been for a smaller, not larger, role by the attorney general. Critics have often lobbed accusations that the official titles and summaries drafted by attorneys general can be crafted to suit one political position or another.

There have been many other ideas, too, including more legislative power over initiatives. A 2014 law signed by Gov. Jerry Brown made a few notable changes (including a new public comment period that's the focus of calls for action by opponents of this initiative). But the long-standing maxim is that giving elected officials more power over the initiative process would conflict with the basic tenets of a system designed to be independent of elected officials.

Will The Anti-Gay Initiative Spark A Broader Effort?

But at least one observer says the furor over the anti-gay initiative should lead to an important change in state law.

"When you are taking away fundamental human rights -- as in the right to live -- it is appropriate to give our public officials a formal exception that they can invoke to block an initiative that violates fundamental human rights," wrote political journalist Joe Mathews in an online column on Monday. Mathews argued that even without such a change to the system, Attorney General Harris should test the existing legal boundaries by refusing to process this initiative.

No doubt there could be a political upside to such action (especially for someone running for statewide office in 2016); but others may worry about ensuing legal precedents that could impact other, less black-and-white, initiative proposals.

Others say the state could discourage frivolous proposals by hiking the $200 fee charged to file an initiative, though that could also enrage those who already feel as though the system favors influential interests over grass-roots groups.

The bottom line is that unusual -- often unworkable, illegal or downright odd -- initiatives are often submitted for review and circulation. A sampling of the more colorful ideas in recent years:

In case you missed it: None of these ever happened. In fact, none of the backers even submitted signatures from California voters.

Certainly, what sets these proposed laws apart from the current proposal is the idea of legalized, vigilante violence against one group of California men and women. But like other far-flung proposals, the real limitation is the support of other voters -- their signatures on an initiative petition.

While it's now easier than it's been in decades to qualify an initiative (fewer signatures and a slightly longer time to gather them), it's still a very high hurdle unless you've got a lot of money or a well-organized and large army of volunteers.

But the author of the self-proclaimed "Sodomite Suppression Act," Matt McLaughlin, has gone radio silent when reporters have tried to contact him for comment. Other than

But the author of the self-proclaimed "Sodomite Suppression Act," Matt McLaughlin, has gone radio silent when reporters have tried to contact him for comment. Other than