Between 1848 and 1852, San Francisco exploded from a town of just over 800 people to a port city of about 35,000 people. Among those who flocked to the city, which served as immigrants' main gateway to newly discovered gold fields in the Sierra Nevada foothills, were illustrators, photographers and mapmakers, who documented the city's shockingly quick rise.

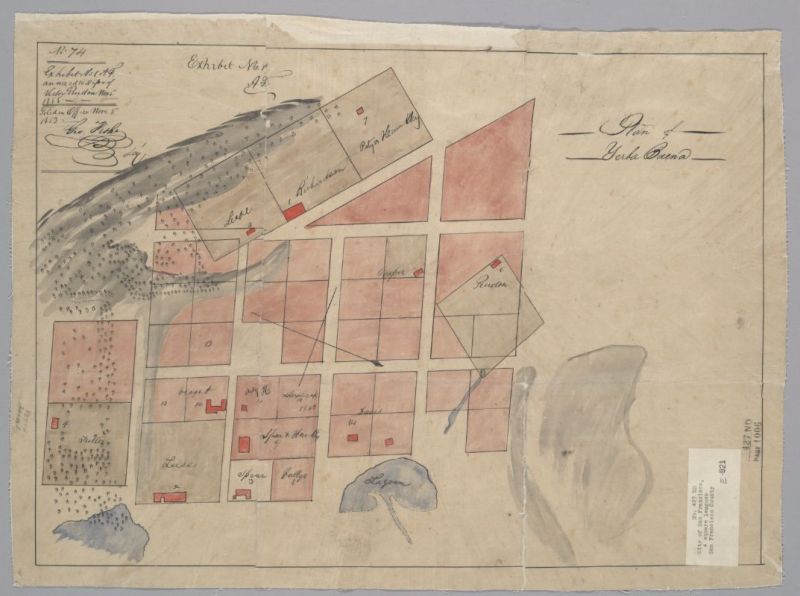

Above: Jean Jacques Vioget, a French-born ship's captain who arrived on San Francisco Bay in 1837, was among the first to settle in the village of Yerba Buena. In 1839, Mexican officials hired Vioget to survey and map the settlement. The area he laid out is roughly bounded by today's Pacific Avenue to the north, Washington Street to the south, Grant Avenue to the west and Montgomery Street to the east. The map is oriented with west at the top; the bay would be below the map's bottom border.

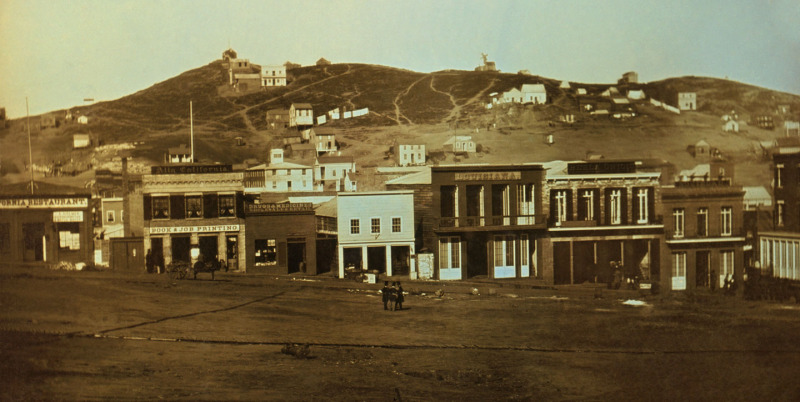

Above: San Francisco's Portsmouth Square, also known as the Plaza, seen in a daguerrotype dated 1851. The view is toward the west, with the pictured buildings along Dupont Street (now Grant Avenue) and the heights later dubbed Nob Hill. The image was credited to a dentist named S.C. McIntyre. (Wikimedia Commons/Library of Congress)

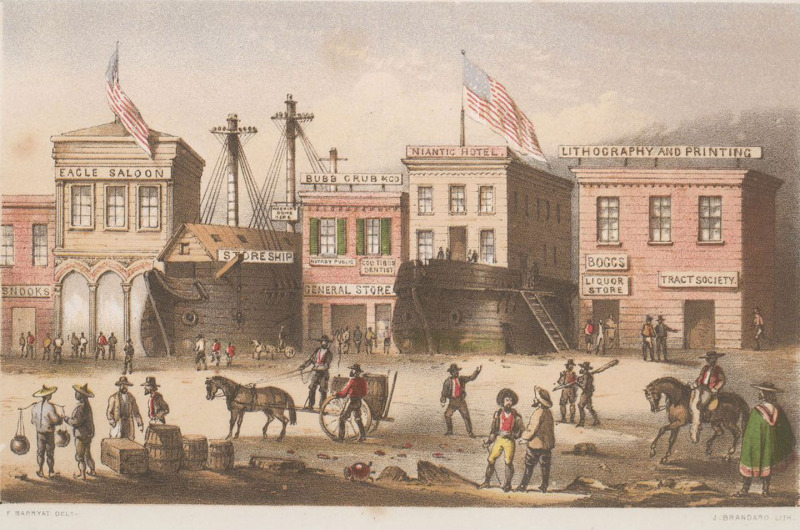

Above: Hundreds of ships arrived in San Francisco during the Gold Rush, and many were abandoned as crews deserted to go to the gold fields. Some of the ships, like the whaling ship Niantic, were hauled ashore and incorporated into the city's earliest waterfront neighborhoods. The Niantic, shown here in a lithograph by wandering memoirist Frank Marryat, was pressed into service as a hotel near the corner of Clay and Sansome streets. The ship/hotel was destroyed during a fire that swept much of downtown in May 1851. (See: Niantic: Buried Gold Rush Ship.)

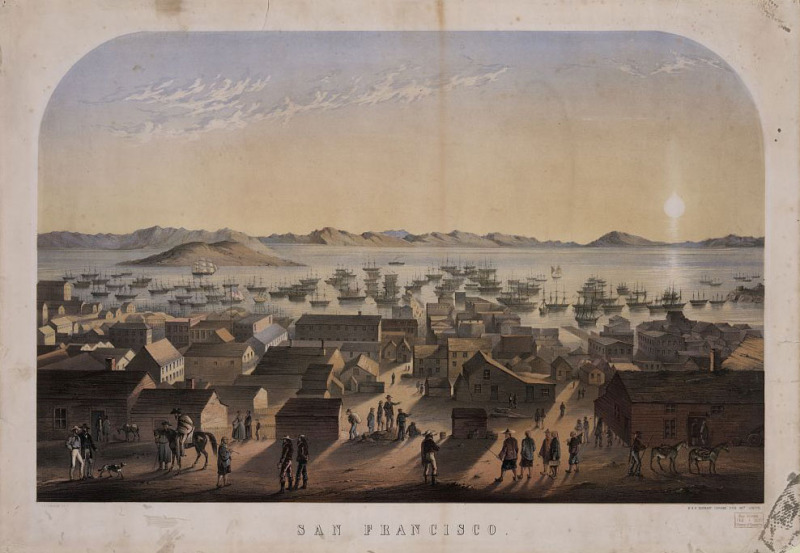

Above: A Frank Marryat view of San Francisco looking east across the city toward the bay. Yerba Buena Island is pictured at the left, with Mount Diablo visible in the distance at center.

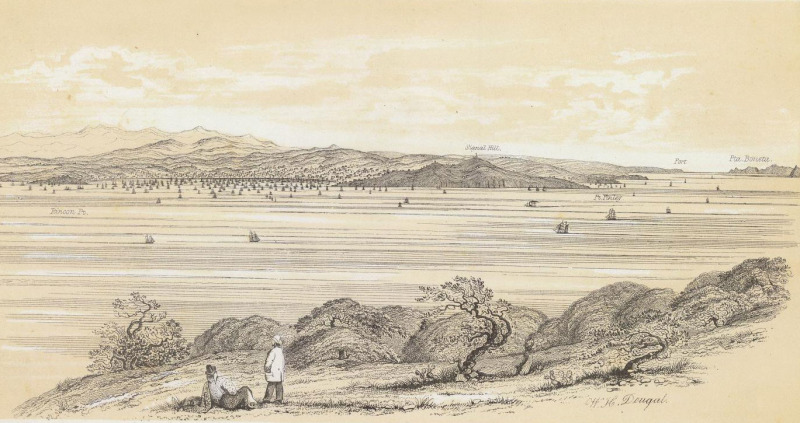

Above: And here's what the rapidly growing city looked like from the shore of Yerba Buena Island in 1852.

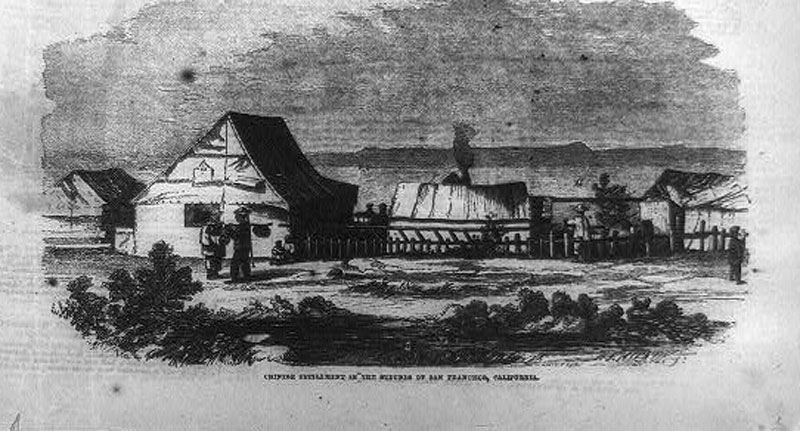

Above: This engraving, published in Frank Leslie's illustrated newspaper in June 1856, shows a Chinese settlement on the fringe of San Francisco. In 1852, about 20,000 Chinese immigrants registered at San Francisco customs houses -- most intending to travel inland to the gold fields. California imposed a Foreign Miners Tax that May; the levy of $3 a month was explicitly directed at Chinese miners. Violence increased soon after 200 Chinese miners were robbed and four murdered at Rich Gulch that year, according to the Daily Alta California.

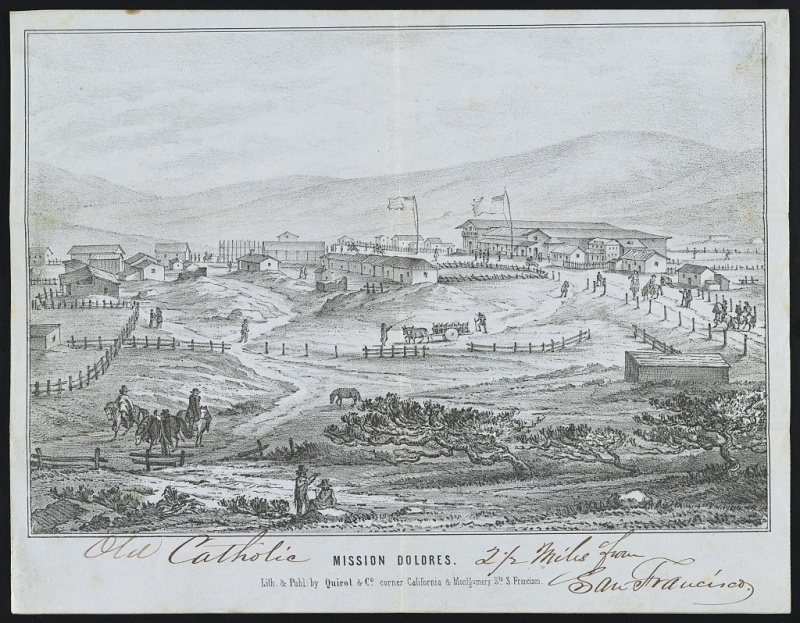

Above: An early 1850s image of Mission Dolores, which despite San Francisco's rapid growth still lay well beyond the city's borders.

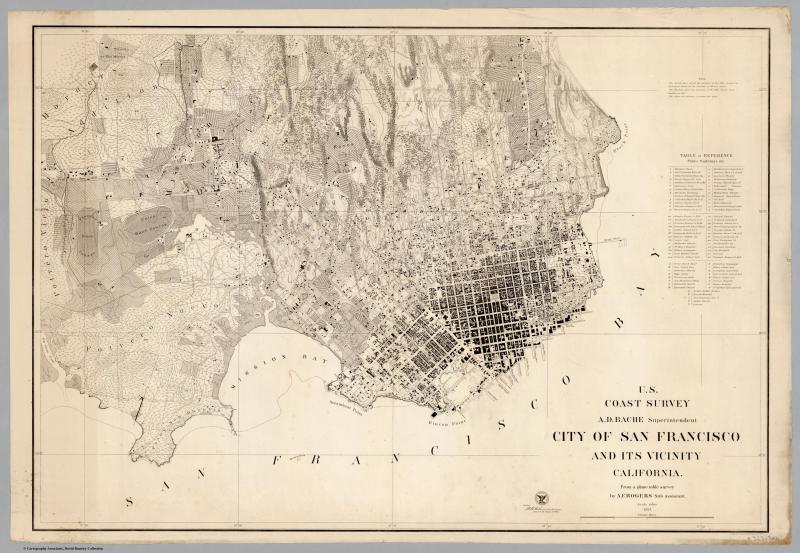

Above: An 1857 map of San Francisco demonstrates the city's rapid growth.

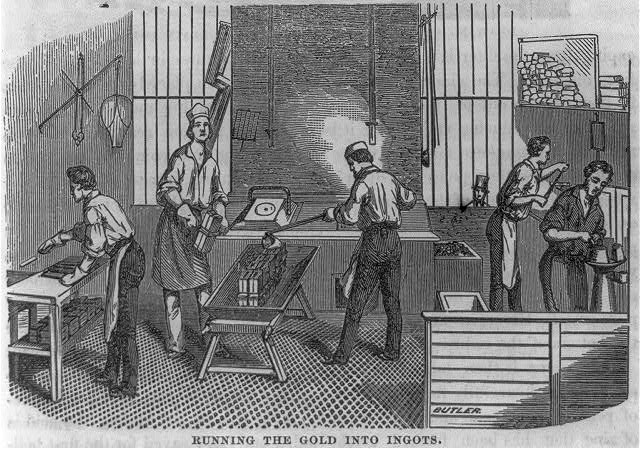

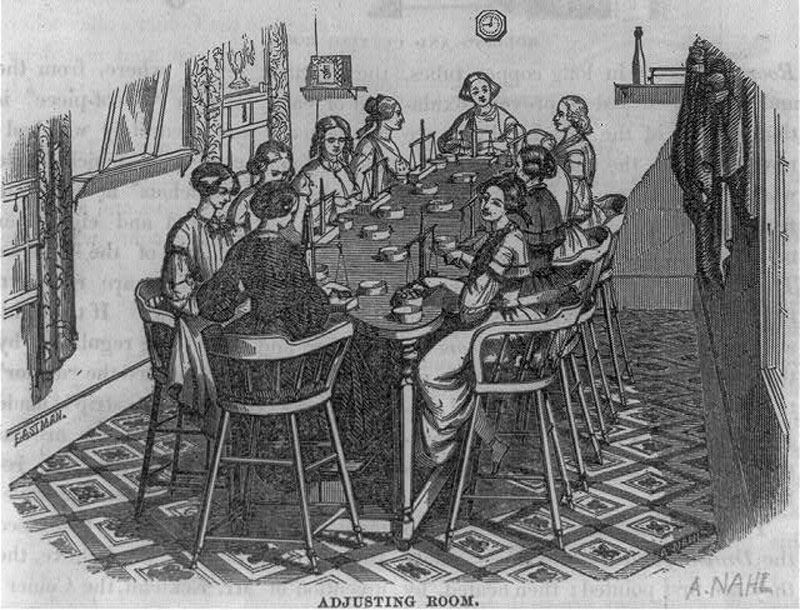

Above: This is one of several line engravings created by A. Nahl in 1856 showing workers at the San Francisco Mint, built just two years prior. Workers produced $4,084,207 worth of gold coins in 1854 alone, according to the U.S. Mint. The new mint quickly outgrew the small brick building and moved to new headquarters at Fifth and Mission streets -- today's "Old Mint" -- in 1874.

Above: Women worked at mints throughout the United States during the mid-1850s. By 1860, women at the Philadelphia Mint earned 11 cents an hour and often worked 10 hours a day. San Francisco's mint was originally a branch of the Philadelphia Mint.