Factors in and outside the school affect results, she said, including students’ chronic absences, which were among the highest in California since the pandemic. The number of tutors within a school, how they were deployed, the size of tutoring groups and scheduling are also among the many variables.

Another factor is the uneven support of teachers and principals, Jochim said. Among tutors responding to a survey, only half reported daily communication with classroom teachers, and fewer said they were in regular communication with school staff leading the literacy work.

“There are gaps; this is where greater attention to quality and fidelity in tutoring is important,” Jochim said.

Lakisha Young, founder and CEO of The Oakland REACH, noted that her group has helped the district increase the number of tutors available. “But if we don’t work on these other conditions to bring everything into alignment, then it’s going to make the work harder,” she said.

Jochim said that the center will spend the last year of a two-year grant collecting more data to determine how school differences affect outcomes. She said the most instructive lesson from the pilot is that having more adults in the classroom allows for differentiation of instruction.

“For so long in this country, we have assumed that a single teacher working alone in their classroom could sufficiently differentiate instruction for kids in literacy and math,” she said. But that’s difficult, she added, in a kindergarten class where some students are reading for comprehension while others struggle to decode one-syllable words.

Jochim said there is “no question that this project is the right approach.”

“Differentiation of instructions is the ticket to better outcomes — if we can figure out the specifics,” she said.

Susanna Loeb, a Stanford education researcher and authority on tutoring, is also bullish about the approach. The Oakland REACH’s partnership with the district and FluentSeeds matters, she said, because it treats tutoring as “part of a broader and coherent approach to improving literacy, not simply an ‘add-on’ program.”

“I’m excited,” Loeb added, about “what this systemic approach can offer for communities across the country.”

The level of pay may also determine if the tutoring initiative succeeds. The district pays tutors $16 to $18 per hour, plus benefits, which Young had to lobby the district for. Tutors who responded to the survey cited low pay as the biggest disincentive to the job, and it is likely a factor in why only five of the 11 tutors placed last spring returned to the job this fall.

Young acknowledged that pay appears to be the biggest obstacle to sustainability, and she is exploring other options to fill the income gap, such as a retention bonus.

The Oakland REACH incubated the concept of community-trained tutors in the COVID-19 summer of 2020. Parents frustrated by the failures of remote learning had cited reading instruction as their top need, so Young hired the first group of tutors. Buoyed by their success, she began working closely with the district to prioritize early-grade reading tutoring.

Young’s group recruited the first cadre of 16 “literacy liberators” by handing out fliers on school grounds and going door-to-door in the fall of 2022 and partnered with FluentSeeds to train them in early 2023. Many recruits had to be convinced they could do the job; the minimum requirement was a high-school degree.

According to the report, the first recruits included a young man who had seen family members struggle with reading comprehension and a retired teacher who “expressed alarm” that he had mistaught young readers and wanted to make amends through the science of reading — instruction grounded in structured literacy and evidence-based practices.

Oakland Unified hired 11 of them to fill tutoring vacancies and placed them in the classrooms last spring.

“Six months into the school year, Oakland had still not filled tutor positions in schools that served the most marginalized students. Oakland REACH was really critical to filling the gaps and ensuring the kids who most need this help are able to get it,” Jochim said.

A second cohort of 20 tutors began work in the fall of 2023.

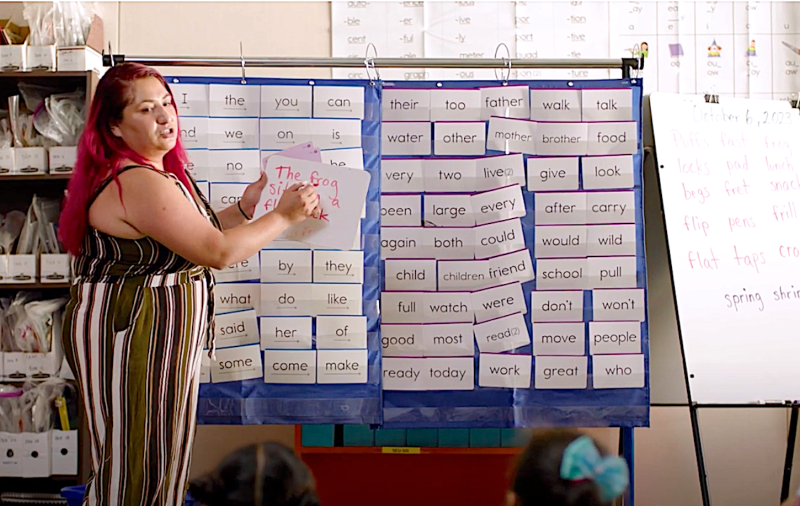

FluentSeeds gives all of Oakland’s K–2 literacy tutors a four-day course in SIPPS — Systematic Instruction in Phonological Awareness, Phonics, and Sight Words — the district’s early-stage intervention program. The subset of tutors that The Oakland REACH recruited for “literacy liberator fellowships” took an additional set of eight two-hour sessions that provided background in the science of reading and focused on building student mindsets and tutors’ roles as leaders and advocates.

“We bring in a social-emotional component of what it means to be a teacher in Oakland teaching students that are behind, and how does that make them feel?” said Emily Grunt, program director for FluentSeeds, who has led the Oakland training.

One tutor characterized the fellowship as “life-changing.”

Interest in the program appears to be spreading: The Oakland Reach’s recent conference on the tutoring model attracted representatives from 14 nonprofits nationwide, and another conference is planned for the spring.

The group also created a readiness assessment to determine if other organizations have the leadership capacity and organizational strength to take on the work effectively.