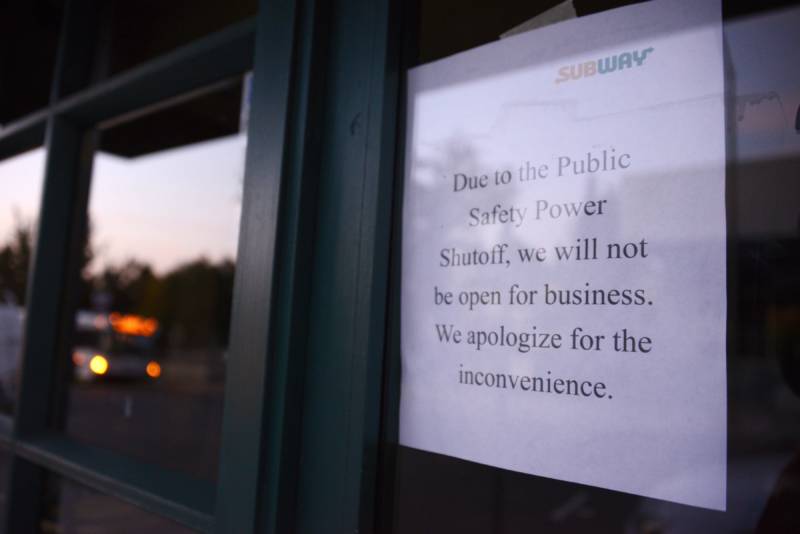

Earlier this week, PG&E made the controversial decision to cut off power to about 738,000 customers across California due to heightened fire risk. While the power was restored in the Bay Area on Saturday afternoon, there are still questions over why the widespread shutoffs were necessary, and if they'll happen again.

Our reporters participated in a Reddit AMA on Friday to try to answer some of those questions. Contributors were:

- Lisa Pickoff-White, KQED News data reporter who’s been tracking PG&E’s affairs

- Lauren Sommer, KQED Science reporter covering climate change, water and energy.

- Danielle Venton, KQED Science editor and reporter covering wildfires, astronomy, and physics

- Jeremy Siegel, KQED News reporter and weekend afternoon news anchor/editor covering the Camp Fire

Below are some highlights from the AMA, which have been edited and condensed for length and clarity.

Who Made the Decision to Shut Off Power?

Lisa Pickoff-White: The short answer is that the utilities (i.e. PG&E) make the decision to shut off the power and then those decisions are assessed later.

There is a process and oversight. Forty eight to 72 hours before utilities shut off the power, they are supposed to notify firefighters and other emergency responders, including Cal Fire, Cal OES and local groups. If they’re planning on turning off transmission lines, the lines that carry high voltage electricity from plants to substations, they also have to notify Cal ISO.

Then, after the fact, utilities have to file reports about the shutoffs with their regulator, the California Public Utilities Commission. You can see one of those reports here.

What Actions Will Local and State Governments Take to Prevent the Shutoffs From Becoming More Frequent?

Jeremy Siegel: It remains to be seen what they’ll actually do, but there’s definitely talk among legislators that something must be done to prevent this from becoming the new normal. We’ve been talking to state lawmakers who say this will be a big subject of conversation when the legislature reconvenes.

In a press conference on Thursday, Gov. Gavin Newsom was asked about this, and he said something along the lines of: even if PG&E became publicly owned, that’s not going to fix everything.

That's because, according to Newsom, their infrastructure is old, it’s got problems, it needs to be fixed. And that’s gonna take a lot of time and a lot of money.

So even if California were to take control of the utility, it’s not like they could snap their fingers and get rid of this problem. Regardless of who is in charge, it could take a long time to find a less disruptive, permanent solution.

What Would it Take to Get California's Infrastructure to a State Where Shutoffs Aren't Necessary?

Danielle Venton: PG&E hasn’t put out any projections of how much money it would take to harden their grid from these strong winds that we see every few years. We do know that burying lines is expensive — millions of dollars per mile.

Our colleague Kevin Stark addressed this somewhat in the FAQ we did earlier this week:

"For new construction, PG&E places most power lines underground, so its main issue is dealing with 81,000 miles of existing overhead lines.

That’s no small feat. A little back-of-the-envelope math: Strung together, the lines would extend from San Francisco to Buenos Aires and back about four times. Burying lines is very expensive. On its website, PG&E estimates it would cost $3 million per mile to put its lines underground. So $3 million x 81,000 miles = $243 billion, which is more than California’s entire 2019 budget. One report suggests that burying lines in urban places can be even more expensive — up to $5 million a mile.

Still, consumer safety advocates argue that leaders in Sacramento should require the utility to bury lines in heavily populated, high-risk fire areas." — Kevin Stark

What's the Craziest Thing You've Found While Covering This Whole Thing?

Lauren Sommer: Okay, this may not be “crazy,” but I spoke to a U.C. Berkeley researcher who has 500 caterpillars in his living room because of the blackouts.

The campus lost power this week, so many researchers took their specimens home since they weren’t sure they would have emergency power. Another researcher took home 10,000 tiny swimming crustaceans in aquariums that need power. They also trucked 17 freezers of specimens across the bay to UCSF to help preserve them.

Our reporters answered many more of your questions, you can read them all here. Looking for more answers? Check out our full coverage of the public safety power shutoffs here.