What can we learn about economics, war or politics from a mollusk shell? Quite a lot, according to Geerat Vermeij. The UC Davis evolutionary biologist studies mollusk shells, and he uses what he learns to make insights on everything from the dangers of capitalism to the evolution of law.

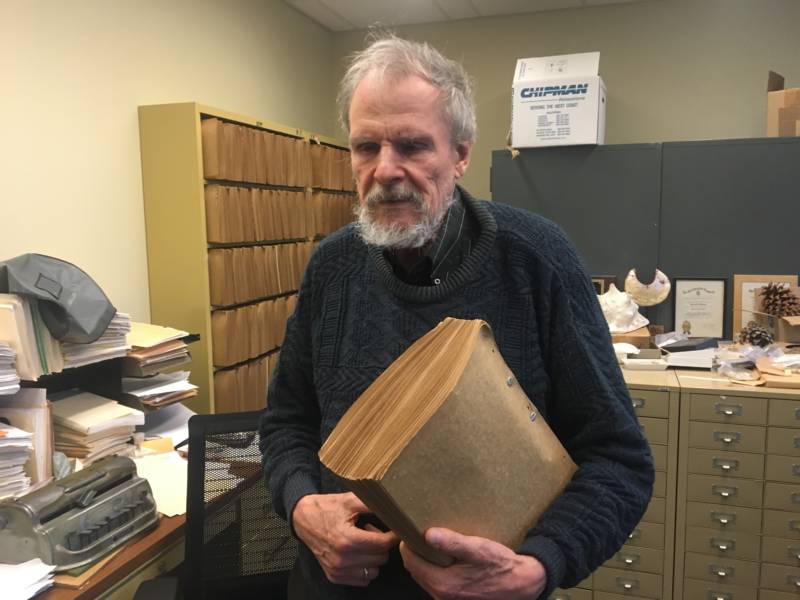

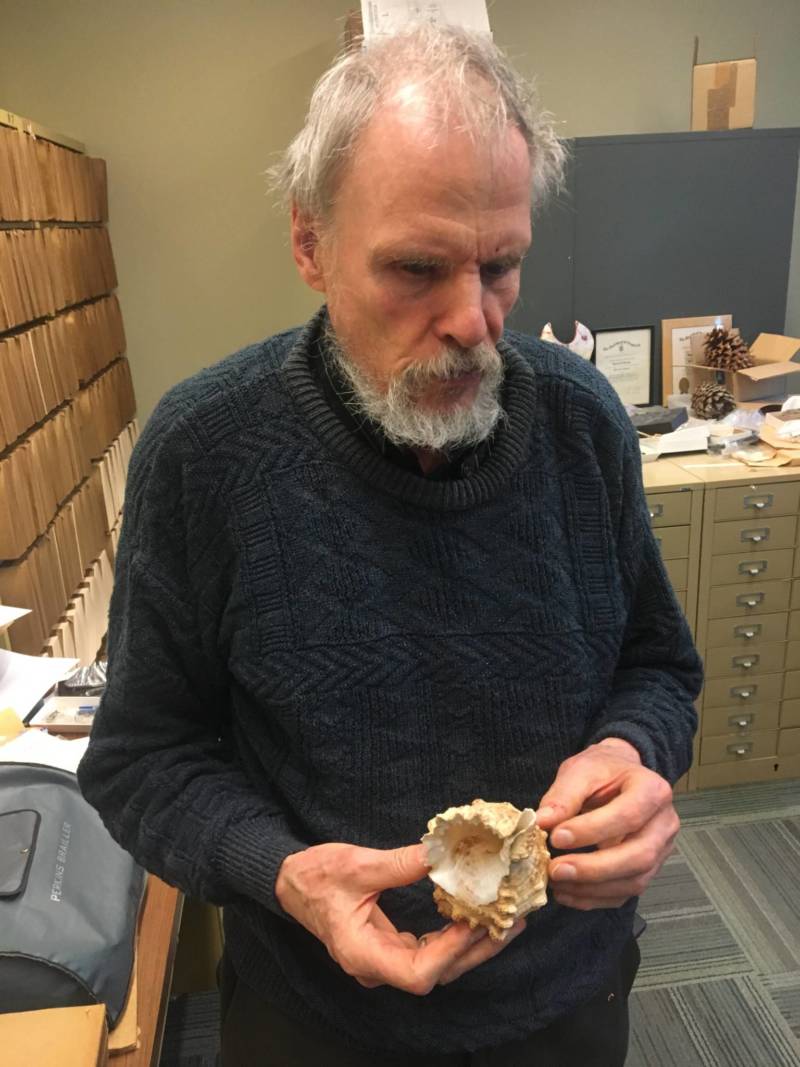

Vermeij has been blind since he was 3-years old. To observe a shell, he takes it in his hands and feels the entire structure. He takes in every detail — the thickness of shell, number of spines, dimension of the spiral, any of the myriad grooves, teeth and crenelations on its surface.

"Shells are all beautiful in their own way," Vermeij says. "But I look beyond their beauty and at what they’re trying to tell me."

Each detail on a shell holds a secret. A small nick can show where a crab attacked. Growth lines tell how fast it grew. The spiral structure lets you feel how the creature burrowed into sand. Through touch alone, Vermeij can identify a shell, place it in time, and in some cases, determine if it is an entirely new species.

Mollusks have been around for over 500 million years. Each shell helps Vermeij better understand how they evolved — the battles between predators and prey, adaptations and the struggle for survival. That evolutionary history provides insight on human history. For example, Vermeij has found that for mollusks, periods of population expansion — kind of like one that humans are going through right now — only last a short time.

Over the years he has amassed a collection of thousands of shells, which he keeps on hand at his UC Davis office. He’s written over 200 articles and books, including "The Evolutionary World: How Adaptation Explains Everything From Seashells to Civilization." His theories all stem from the intricate details of shells. He spends hours categorizing them all.

"The more I look at shells, the more I see that I haven’t seen before," Vermeij says. "Thinking about big subjects is beautiful. My life is filled with beauty."

This story comes to us from Chris Hoff and Sam Harnett of The World According to Sound podcast. They’re partnering with the LightHouse for the Blind and Visually Impaired in San Francisco to help us reimagine California in the rich way blind people experience it every day. The project has additional support from California Humanities.