Unlike many teachers who choose to work in schools because they were good students themselves, Michelle Carlson understands what it’s like to hate school. As a kid she couldn’t see the point of any of the material she was supposed to learn, and working for good grades without a clear reason wasn’t enough to motivate her. She did eventually graduate high school and went to college because her parents told her it was an important way to gain financial independence. She and her sister had to pay their own way, working at coffee shops and carpooling 40 miles each way to school at Chico State.

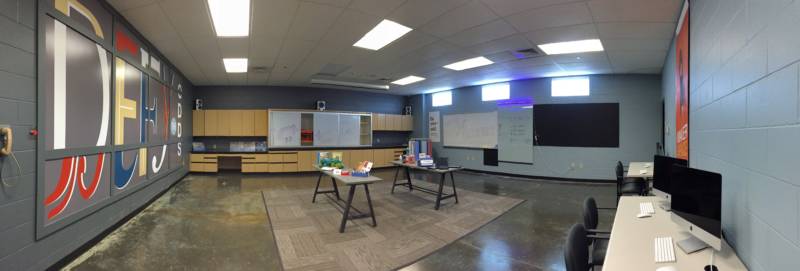

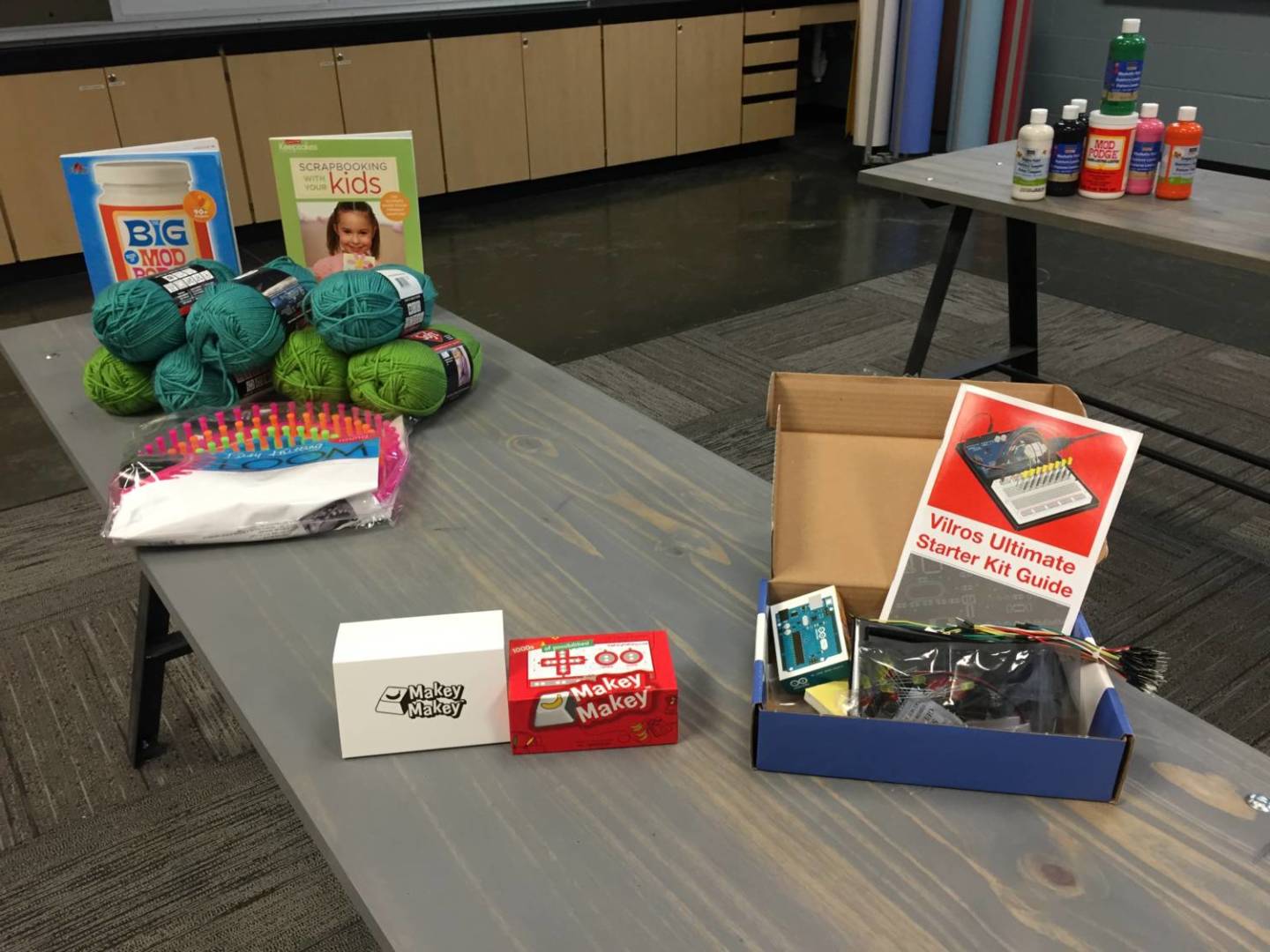

When she graduated, Carlson started a business, but eventually decided she wanted to help make school different for kids in the next generation. She started working at the Tehama County Office of Education and in her spare time created a makerspace in the office. Teachers can bring their classes into the makerspace and its success has sparked some schools to create their own. Older students can also sign up to become Makerspace Ambassadors, where they spend half their time working on passion projects and half their time creating useful things like promotional posters for local businesses and nonprofit organizations.

All kinds of students signed up for the Ambassador program -- some were good students looking to add something to their college applications, while others struggled in traditional school and were looking for somewhere to be themselves. Most didn’t expect much out of the makerspace when they started, but soon found that having the freedom to pursue whatever they wanted with support to learn new skills was incredibly exciting.

Good students who felt like they were charging down a prescribed path because that’s what was expected of them found a sense of purpose and passion for new skills. And students who felt like failures began to see qualities in themselves they’d never recognized before. One such student, Ericka, never felt good enough, but her involvement in the makerspace gave her confidence to apply to college. Now she’s majoring in computer science and getting a credential to teach English language learners.

One day some incarcerated youth from the Tehama Juvenile Detention Facility were released to spend time in the makerspace. That group of students created a suicide prevention video on their own that afternoon with only minimal explanation of how the recording and editing tools work. They ended up winning an award for the video and county Probation Chief Richard Muench approached Carlson, who has since started her own company helping schools and organizations start makerspaces, about building a makerspace inside the walls of juvenile hall.