Games are increasingly recognized by educators as a way to get kids excited about learning. While the stereotype of a “gamer” may evoke the image of a high school boy holed up in a dark room playing on a console, in reality 62 percent of gamers play with other people either in person or online, and 47 percent of all gamers are girls.

Game developers and academics who have been studying the elements that go into making games more attractive to girls found that those very same qualities are also important components of learning. For instance, girls are more drawn to games that require problem solving in context, that are collaborative (played through social media) and that produce what's perceived to be a social good. They also like games that simulate the real word and are particularly drawn to “transmedia” content that draws on characters from books, movies, or toys.

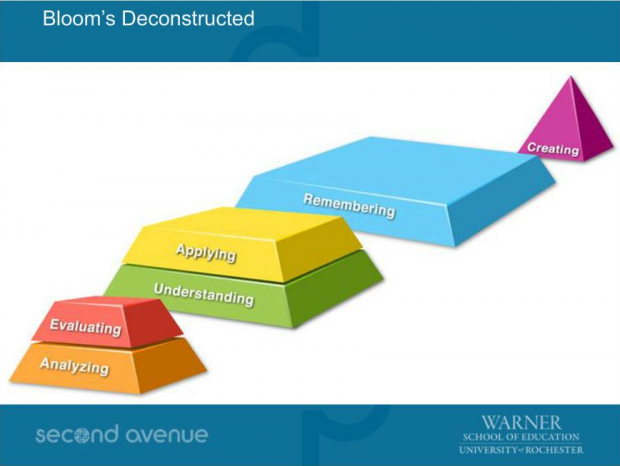

“Something we’ve seen as a tremendous motivator for girls to learn about math and science is that they need to see the connection from the classroom out into the real world,” said Victoria Van Voorhis, the founder of Second Avenue Learning in a recent webinar. Her company has received funding from the National Science Foundation to study how to reach girls through gaming with the help of the Rochester Institute of Technology. They tested a physical science game called “Martha Madison’s Marvelous Machines” with middle school girls in urban, suburban, and rural environments to gauge whether playing the game would increase their interest in science, technology, engineering and math (STEM), whether it appealed to them and if it could improve their understanding of fundamental mechanical devices.

[RELATED READING: What's the Secret Sauce to a Great Educational Game?]

“When we asked them about springs and levers, they had no understanding of why they were important in the real world,” Van Voorhis said. “But when we were able to situate those kinds of tools in a real-world context, where they were solving a problem that was directed towards social good, we saw the engagement numbers pop.” girls were talking about physics or game play 76 percent of the time and were only off topic 5 percent of the time.