Encouraging this acceleration of digital chunky content, in large part, is the Open Educational Resources (OER) movement.

OER, though definitions vary, is at its heart digital instructional content that's designed to be mixed, modified and shared. In other words, a teacher can pick and choose learning elements he or she needs for a lesson from a variety of sources, make changes, use those lessons in class, and theoretically then distribute either the individual pieces or the completed combination to other educators for their use.

OER, though definitions vary, is at its heart digital instructional content that's designed to be mixed, modified and shared. In other words, a teacher can pick and choose learning elements he or she needs for a lesson from a variety of sources, make changes, use those lessons in class, and theoretically then distribute either the individual pieces or the completed combination to other educators for their use.

It’s like creating your own music playlist by choosing tracks from various artists and sequencing them any way you want.

Overall, four core factors have come together to fuel the rise of digital content, including OER pieces, across the educational landscape, from kindergarten to college:

PRICE. Ask any educator the appeal of OER you'll likely to hear, “It’s free content.” While that may not always be true (there is OER available to institutions by subscription through the delightfully named HippoCampus, for example), and not all digital content is OER (just ask any education industry company), perceptions do matter. And the perception that a lot of quality content is available for only the cost of labor has led a lot of school districts and teachers to try it during difficult budget times.

AVAILABILITY. Spurred by entrepreneurs and fueled by funding from, among others, the Gates and Hewlett Foundations (as well as the continued efforts of long-time educational publishers and ed-tech companies), there's simply a lot more digital content on the web than there used to be, for example Khan Academy videos and materials from NASA. But significantly more has been developed by existing educational powerhouses, start-ups and educators themselves. Anything digital, and granular enough, works.

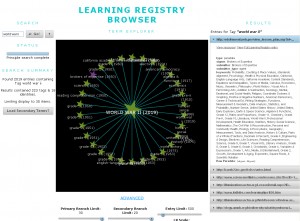

DISCOVERABILITY. A big challenge has simply been finding what online materials exist on the web beyond known repositories such as Curriki. Two very prominent, and public, initiatives are tackling this.

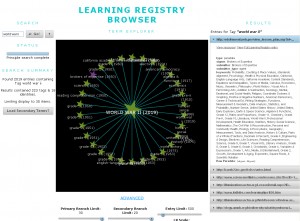

Last November, the U.S. Departments of Education and Defense launched the beta of the Learning Registry, which is basically a directory of kindergarten-through-adult digital education resources from a wide variety of government, state, district and private sources. What makes the Registry unique is that any provider can register content (the National Archives, Smithsonian and PBS were among the early participants), and any educator can quickly find lessons plans and content specific to his or her unique needs based on subject, grade level or other criteria. And the Learning Registry doesn’t just reside at one address on the web; it’s more of a embeddable, distributed index that can be browsed from many websites.

Last November, the U.S. Departments of Education and Defense launched the beta of the Learning Registry, which is basically a directory of kindergarten-through-adult digital education resources from a wide variety of government, state, district and private sources. What makes the Registry unique is that any provider can register content (the National Archives, Smithsonian and PBS were among the early participants), and any educator can quickly find lessons plans and content specific to his or her unique needs based on subject, grade level or other criteria. And the Learning Registry doesn’t just reside at one address on the web; it’s more of a embeddable, distributed index that can be browsed from many websites.

A second, related effort is the Learning Resource Metadata Initiative. Steered by the Association of Educational Publishers and Creative Commons, LRMI is a fast-tracked project, launched just last June, to make it easier to find educational resources via major search engines such as Google, Bing, and Yahoo. At its core, this is about consistently tagging digital educational content – no matter who creates it – with metadata that search engines understand.

Taken together, the hope is that LRMI and the Learning Registry will go a long way toward solving the problem of highlighting appropriate educational chunks.

FLEXIBILITY. A large part of the appeal of digital chunked content is its flexibility. Pluto’s planetary status in flux? Swap out chunks without wiping out the lesson or course (but keep the old one, just in case the astronomical protests are successful). And flexibility goes beyond delivery via pixel.

FLEXIBILITY. A large part of the appeal of digital chunked content is its flexibility. Pluto’s planetary status in flux? Swap out chunks without wiping out the lesson or course (but keep the old one, just in case the astronomical protests are successful). And flexibility goes beyond delivery via pixel.

Utah, for example, has the Utah Open Textbook high school science curriculum. Created from OER content, the course textbooks are then printed and distributed. But the cost is $5.35 per book, versus about $80 for a traditional science textbook, prompting the project’s David Wiley to note at this year’s SXSWedu conference that these become books kids mark up and keep, rather than having to turn in at the end of the year.

In higher education, AcademicPub allows digital textbooks to be created with a mix of copyrighted (paid) and open (free) content. The automated process leads to a custom electronic or paper book – essentially, a digital course pack. And there are several other examples.

But the increased use of chunked digital content, especially OER, is not without pitfalls. The overused phrase, “free like a puppy, not free like a beer,” applies to any effort that replaces publisher cost with teacher labor to find, assemble and maintain content (even if, once assembled ,content is shared). And if the materials aren’t printed, every student has to have access to a hardware device that properly displays the content.