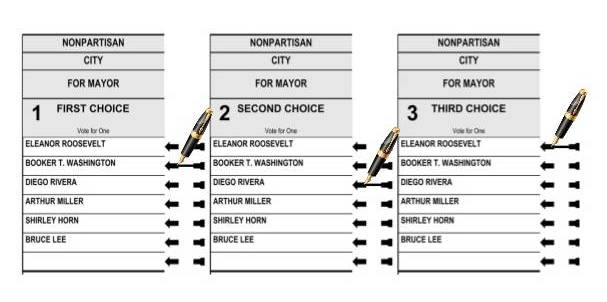

If any candidate receives more than 50 percent of first-choice votes, that candidate is automatically elected. Game over. But if no one receives a majority, a second round of counting proceeds. The candidate who received the least number of votes is eliminated (and if you voted for that candidate, your vote goes to your second choice pick). This process is repeated until one candidate has a clean majority.

In it's endorsement of the state's RCV measure, the League of Women Voters of Maine note that in nine of Maine's last 11 gubernatorial elections, the winner failed to receive a majority of votes. RCV, it concludes, is "the best way to ensure a majority vote in competitive, single-seat, multi-candidate elections."

Keep in mind that RCV is different from California's top-two primary system, in which all candidates are listed on the same ballot and the top two vote-getters, regardless of party affiliations, advance to the general election.

Round 1: The Sesame Street Power Grab

So just for kicks (and because puppets are more fun than politicians), let’s pretend we’re observing a heated street council race on "Sesame Street." There are four candidates running, and a total of 24 neighborhood voters casting ballots.

Cookie Monster (the clear front-runner, of course, well-loved for his oratorical gifts and promises of free pastries to the electorate) gets 10 first-place votes.

Oscar the Grouch gets eight first-place votes (with strong support from the waste management industry and a large contingent of the generally disgruntled).

Big Bird gets four first-place votes (from aviary supporters). And poor, impetuous Grover gets only two first-place votes (because no one knows who he really is).

Because no candidate received more than 12 votes, there’s no clear majority after the initial round. But we do have our first loser -- better luck next time, Grover -- so we move on to Round 2.

Round 2: The First Elimination

Grover, the candidate with the least amount of first-choice votes, is outta here! But for the two voters who picked Grover as a first choice, their second-choice votes still count. Here’s how:

One of the voters who chose Grover picked Oscar as a second choice. So that vote goes to Oscar (who now has a total of nine votes). The other voter in Grover’s fan club picked Cookie Monster as a second choice. So, that vote goes to Cookie Monster (who now has 11 votes).

At the end of Round 2, here’s the tally:

C. Monster: 11 votes

Oscar: 9 votes

B. Bird: 4 votes

Still no clear winner (because there are still three candidates standing), so on to Round 3 we go!

Round 3: The Deciding Moment

Three candidates left, and Big Bird’s got the least amount of first-choice votes (only four), so that oversized avian is cooked!

Now, we look at the second-choice votes of those four voters who picked Big Bird as their first choice. Remarkably, as it turns out, all four of Big Bird’s second-choice votes were for Oscar! That means Oscar picks up four more votes, giving him (or it?) a final tally of 13 votes to Cookie Monster’s 11.

And thus, that grumpy, trash-dwelling green goon is the new boss in town.

In your city's races, things might not be quite that simple (and all the candidates will likely have noses). But hopefully you're beginning to get the idea of how a candidate can viably receive the most first-choice votes and still lose the election.

In 2010, for instance, Oakland first used RCV for its mayoral race and witnessed a similar outcome: there were 10 candidates, and Don Perata, the clear front-runner (who vastly outspent his opponents during the campaign), got 35 percent of the first-choice votes. That left Jean Quan in a distant second with only 24 percent of first-choice votes. But Quan -- who anticipated this outcome and allied herself with other underdog candidates and their supporters -- received many more second-choice votes than did Perata. And after all the elimination rounds, with second- and third-choice votes factored in, Quan ended up with 51 percent of the vote to Perata’s 49 percent.

The Pundits

So is RCV a good thing? It really depends on who you ask. (Jean Quan, I’m guessing would say yes; Don Perata … not so much. And Oscar the Grouch ... definitely a big fan.)

Like pretty much everything in politics, the system’s got its strong supporters and staunch enemies.

RCV supporters say:

- It could save taxpayers millions by eliminating the need for local primaries and separate runoff elections.

- It lessens the influence of campaign spending. Because RCV eliminates primaries, candidates only need to raise money for one election per cycle, not two or three.

- It gives underdog and third party candidates a fighting chance and produces a winner who is supported by a clear majority.

- It discourages mudslinging and negative campaigning; candidates are now more likely to ally with each.