The writing workshop has been at the heart of my upper-elementary classroom since I began teaching 13 years ago, but the tech tools my students use to publish their work have evolved with the times. In recent years, Plasq’s ComicLife has become an indispensable digital addition to my students’ writing toolkit. What, at first glance, may look like a few motivating bells and whistles has, for me, become essential and transformative. ComicLife is ideal for the differentiated classroom. I rely on it to not only challenge eager writers, but also to reach reluctant ones. The tool’s intuitive, drag-and-drop design is simple enough to use with grades 4 and up. Beginners can work from pre-made templates, and more advanced or ambitious students can create their own designs from scratch.

Audience & Authenticity

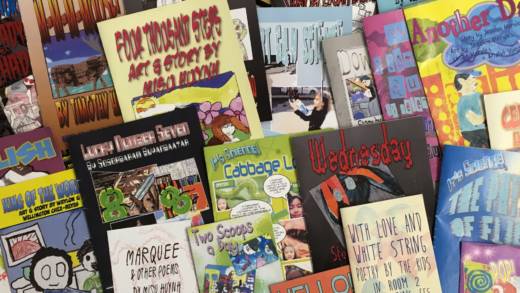

As research on how students learn drives a shift toward authentic learning, teachers are, more than ever, looking for real-world contexts around which to build inquiry-based curricula. Learning to fine-tune narrative voice and identify an audience are key to developing fluidity as a writer, but often traditional activities designed to hone these skills are artificial (i.e., “Imagine you are a pilgrim”-style canned prompts and scenarios). ComicLife breaks the seal on the stale paradigm of the teacher as the students’ only audience. My students write with the understanding that their work will ultimately be published as comic books or graphic mini-novels for other kids their age; their audiences are much bigger than just me. Something real is at stake.

Steam Connections

Publishing any piece of writing on ComicLife will involve the STEAM T (technology), A (art/design) and M (math) strands. The more complex the layout, the more real-world (and Common Core-aligned) math a project will involve. For example, measuring for panel size and margins; setting angles and degrees for image rotation; computing panels per page to meet page requirements set by printing services (multiples of four); creating and adhering to a printing budget. To make a ComicLife design even STEAM-ier, students can use the software to publish their science writing. For examples, click the titles to the right. Both were whole-class endeavors that involved writing about engineering experiments, thereby incorporating all five STEAM strands into a single project.

Process: Layout

My students do their comic book/graphic mini-novel layout and illustrations as a last step, after the writing process. I make sure their writing is polished, final-draft quality before they begin this phase. Then we follow the steps below.

- Separate the entire piece of writing into “snapshots” or “moments.” Usually just a sentence or two for each panel, although some students choose to lay out their work more like a picture book, with a single illustration above a paragraph or two of text (like this one). Hit enter a few times between each chunk of text.

- Choose a graphic novel style (or blank project) ComicLife template and then lay out the book, adding a panel for each snapshot/moment and balloons for dialog. If you will be printing the books, make sure to set margins at the beginning of the process. Altering them later will be a hassle that involves resizing any panels that extend too far into the margins. See print or E-Book Options below.

- Copy and paste each chunk of narration into text boxes or balloons for dialog, omitting quotation marks and dialog tags. This step involves some genre translation that I always capitalize on as a teachable moment: In prose, we rely on punctuation and dialog tags to indicate who the speaker is. In comics and graphic novels, balloons point out who’s talking. This is also the stage where students decide whether some bits of narration will be replaced with illustrations. In panels where they decide an image will work in place of text, I ask them to leave themselves a note in a text box about what to draw there.

- Export this rough mock-up as a PDF (and print if desired) to serve as a map to follow as students create illustrations for each panel. As they work on their art, they will often end up splitting or combining panels to fit their aesthetic and page/panel limits.

Process: Illustration

Technique