There are a sea of addiction apps, many connecting people to treatment or augmenting their outpatient therapy, by counting the number of days in recovery, for example, or recording fluctuations in mood or cravings. Some simply encourage users with inspirational quotes or hypnosis guides. Social apps are increasingly a focus, as well.

“Social outlets are critically important,” said Wilson Washington Jr., a senior public health adviser at the federal Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). “You need family support, you need community support, you need system support.”

One such app, SoberTool, offers an anonymous forum for discussion. Sober Grid is a social network — purported to be the largest for people with a chemical dependency — with a news feed reminiscent of Instagram.

But when Lindemer attended the MIT hackathon, she saw a gaping hole among the existing apps — not only could an app foster positive social connections, but it could also help people sever the negative ones.

Michael Kidorf, a psychiatrist and associate director of addiction treatment services at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, told STAT that the social networks of urban drug users tend to include a mix of people who use substances and people who are drug-free.

“As you would expect, people who have more network members who use illicit drugs use more drugs [themselves] and engage in more risky behaviors,” he said by email.

Opioid users also rely heavily on their contacts to secure heroin and other drugs, Kidorf added. Studies consistently show that regular interaction with other users predicts poorer treatment outcomes.

The hard part, he said, is getting people to dismantle and rebuild their social network. “It is relatively easy to tell substance users to ‘change people, places, and things.’ It is much harder to provide a strategy to help them achieve this important goal.”

Hey,Charlie is piloting one such strategy.

Having watched someone close to her — the namesake for Hey,Charlie — struggle with opioid addiction, Lindemer noticed the obstacles people in recovery face. Even for those who receive medication-assisted treatment, “you go live your life and in the day-to-day 24/7 doing normal things, you still are in recovery and you still have to battle these constant environmental triggers,” she said.

As a then-Ph.D. student in the joint Harvard-MIT Health Sciences and Technology program, Lindemer thought an app could help mediate those urges.

Following the hackathon, Lindemer with her co-founder, Vincent Valant, and head developer, Benjamin Pyser, created a company that initially was funded through MIT grants. Now that she has graduated — she has a day job as a scientist at Watson Health in Cambridge, Mass. – the startup is running mostly on funding from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

Hey,Charlie’s business model is their “Achilles’ heel,” Lindemer said.

She wants to ensure that Hey,Charlie is accessible to everybody. “Our goal is that, if we are charging for it, we are not charging the patient. We want it to fit into a treatment program,” which is why the company hopes to eventually demonstrate the app’s clinical efficacy in controlled trials.

The app is still being refined, but the basics are in place. When sending a text to a “risky” contact, or receiving one, a message from Hey,Charlie will pop up: “Wait a minute, are you sure you want to speak to John Smith right now?” If the user decides against communicating, Hey,Charlie can send an automatic response. The app also shares a handful of affirmative messages with the user throughout the day.

For now, Hey,Charlie’s location services simply create a pause (you’re near a risky area). “The idea is that if you are aware of a potentially triggering situation before it arises, you are more mentally primed to handle it effectively,” said Lindemer.

But in the future, Lindemer hopes the app can go one step further. She envisions it not only warning people that they’re approaching a risky location, but suggesting an entirely different path as well. Lindemer wants to partner with local businesses so that Hey,Charlie can say, “Hey, there’s a coffee shop with a discount a couple of blocks away if you’re willing to switch up your route!”

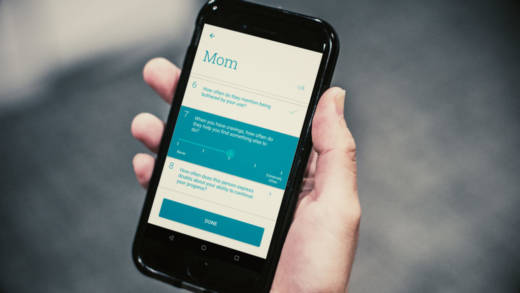

The app relies on a combination of data actively input by users — a one-time occurrence — and data passively collected as they continue to use their cellphones. The onboarding process asks users a series of questions about their contacts, ranked by frequency of communication, and then calculates the risk each contact poses.

Lindemer said that she and her team don’t expect users to be completely upfront and that, especially at the beginning of recovery, relationships can be confusing as they rapidly evolve. Hey,Charlie continues to check in periodically, asking, “Is there anything you want to tell me about this person?”

While the initial version of the app focused on sheltering users from risky contacts, Lindemer and her team are now working to incorporate positive support features as well — letting supportive contacts know when their friend or family member is in a risky place.

“One of the things we know really well is that many people in recovery do have somebody — like a really close family member or friend — who wants to help them, and they often just don’t have the tools, and they don’t know when is the right time to reach out, so we’re trying to address that,” Lindemer said.

Kidorf stressed the importance of supportive, drug-free contacts. His research focuses on how treatment providers can mobilize drug-free individuals to be active participants in their loved one’s recovery.

Hey,Charlie is being piloted at local clinics in and around Boston. Dr. Christopher Shanahan, an internist and professor at Boston University School of Medicine, is leading the effort.

Shanahan, who has been studying substance use for nearly 20 years, loved the idea that Hey,Charlie could be there for his patients when he can’t. He said Lindemer pitched it to him and his colleagues during their journal club hour — when researchers typically discuss new papers published in their field.

“We have, what, 15 to 20 minutes with a patient in a clinic?” Shanahan said. “We give them some advice, a little bit of coaching, and send them out with some buprenorphine — and then it’s a crapshoot.”

The app, he said, is “a very innovative way of addressing the other 23 hours and 15 minutes of the day where doctors aren’t seeing patients.”

But he won’t hang his hat on it. An app can help patients cope with triggers and temptations, but it’s far from the perfect solution, he said.

Kidorf expressed a similar level-headed optimism, noting that apps can bring users closer to people and organizations that can support their recovery. “Overall, I think it is fair to say that these apps can be helpful for people motivated to use them.”

But still, he added, “We have to do better at thinking of opioid use disorder as a severe and often chronic disorder. The best apps in the world will have a hard time competing with it.”