But Berkeley argues that its research tool can easily be extended to use in non-bacterial cells.

That distinction is key since potentially lucrative applications of gene editing in medicine and health will involve eukaryotic cells found in humans.

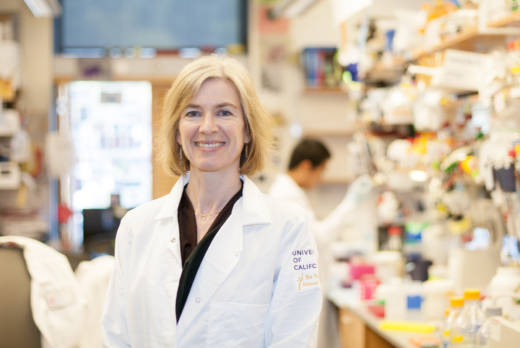

UC Berkeley biologist Jennifer Doudna, who is credited with co-inventing CRISPR-Cas9 now has two options:

1) Appeal to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit

2) Go back to the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office

If Berkeley appeals, the court could overrule the patent office decision in favor of Berkeley.

If Berkeley loses, it could go back to the patent office, where it could be required to narrow its claims, i.e., specifying that its technique is only intended to be used in bacteria.

Or it could get a broad patent that still doesn't specify how to use CRISPR in eukaryotic cells. But according to Jacob Sherkow, a law professor at New York Law School, that could lead to future legal challenges.

"It’s not going to be that strong because anyone who wants to challenge it later can say, 'that patent doesn't disclose how to use the tool in eukaryotic cells,'" says Sherkow.

And the money is in altering those specific cells.

So what's next? Only Berkeley knows; the university has said it will "carefully consider all options."

Science journalists are abuzz about what this means for biotech. Here's a sampling of what they're saying:

1. Berkeley + Broad = Virtual Monopoly on CRISPR-Cas9 (Gizmodo)

Why does this matter? While academic researchers can still use CRISPR for free, companies hoping to harness the gene editing tool to fight disease, solve agricultural problems, or for myriad other potential applications, may have to pay not one, but both institutions, a hefty fee. It’s a decision that has caused some to wonder whether the rights to such revolutionary technology don’t really belong to a third party: the people.

2. Could the Case Encourage Scientists to Be Less Honest? (STAT)

The patent judges concluded that “the inventors themselves were uncertain” about making CRISPR work in human cells.

That could send a terrible message to scientists, said Dr. Robert Cook-Deegan of Arizona State University, an expert on legal and ethical issues surrounding biotechnology. “I hope this does not become the poster child that patent offices use to coach scientists not to be honest about uncertainties about their discoveries,” he said. “The fact that Doudna’s quotes were used by the judges mainly tells me Doudna was being honest. I hope scientists will continue to be honest and not succumb to being told they can’t say things that might undermine a broad patenting strategy.”

3. Fogettaboutit, Companies Can Sidestep Berkeley and Broad (Nature)

Researchers in academia and industry have been pushing CRISPR gene editing beyond the scope of the Broad and Berkeley patents.

Both patent families cover the use of CRISPR–Cas9, which relies on the Cas9 enzyme to cut DNA. But there are alternatives to Cas9 that provide other functions, and a way to sidestep the Berkeley–Broad patent fight.

One attractive alternative is Cpf1, an enzyme that may be simpler to use and more accurate than Cas9 in some cases. The Broad has already filed patents on applications of Cpf1 in gene editing, and has licensed them to biotech company Editas Medicine in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Remember, my friends, if UC Berkeley appeals, this whole process could last through 2020. Or longer.