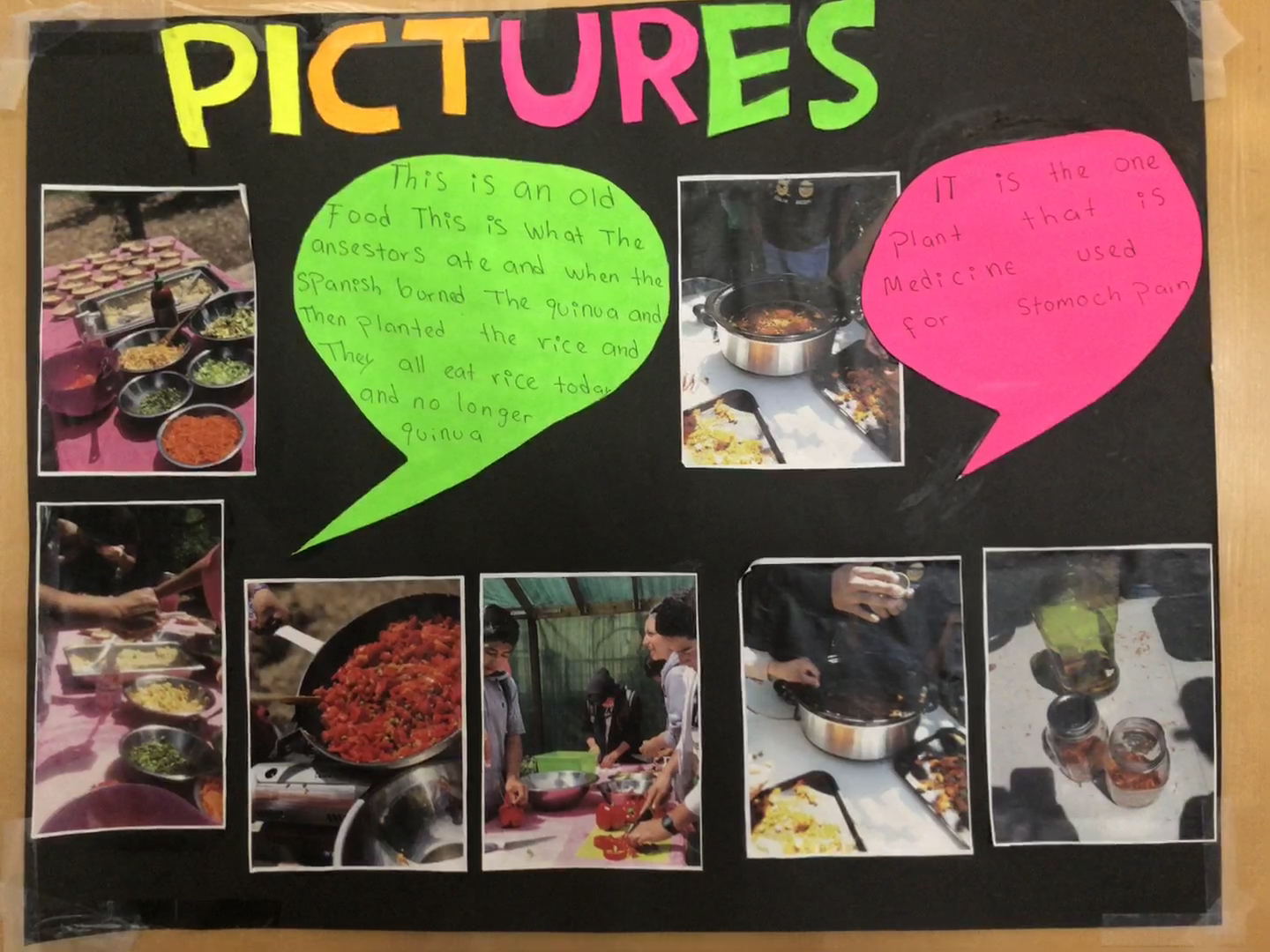

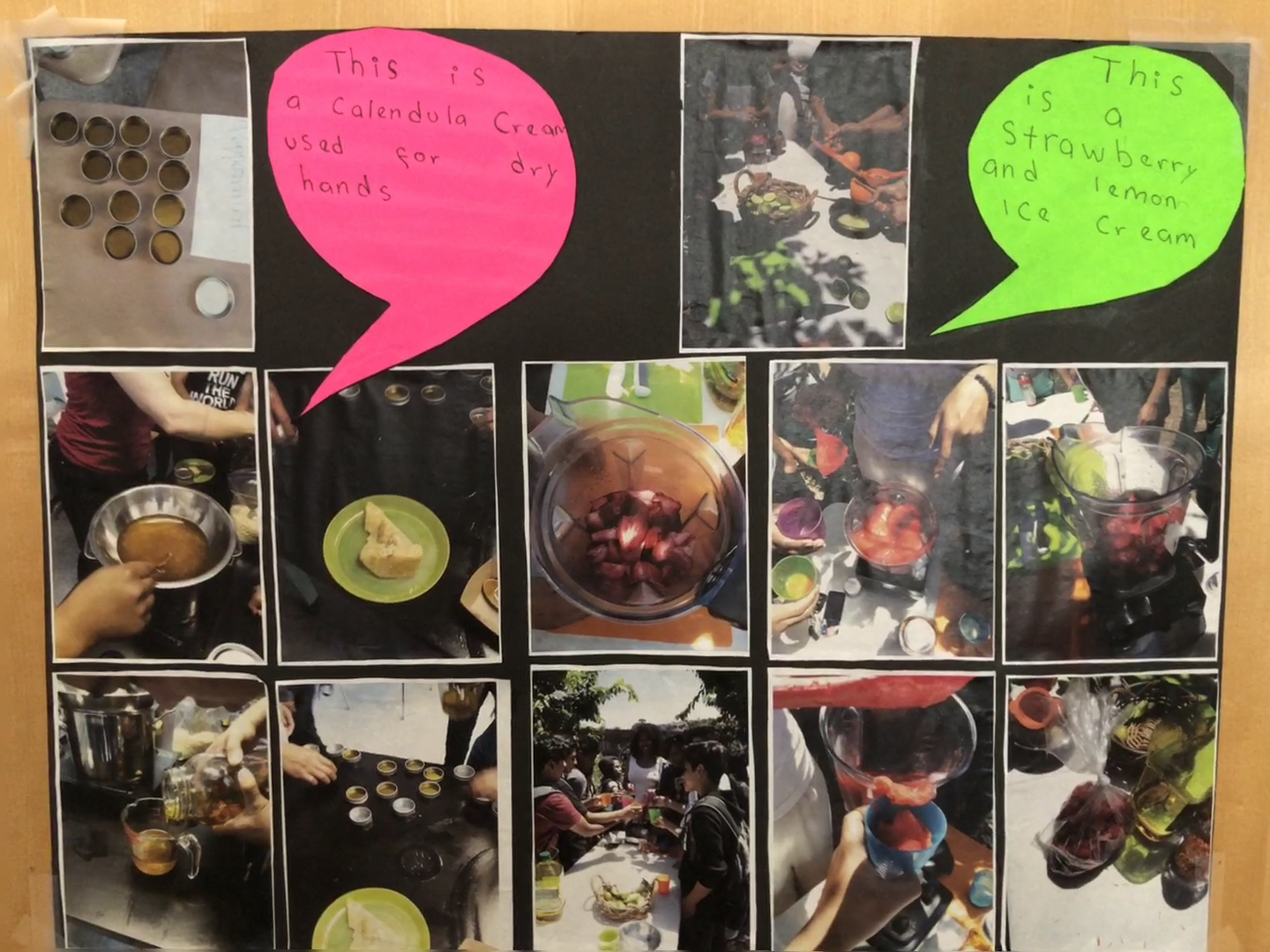

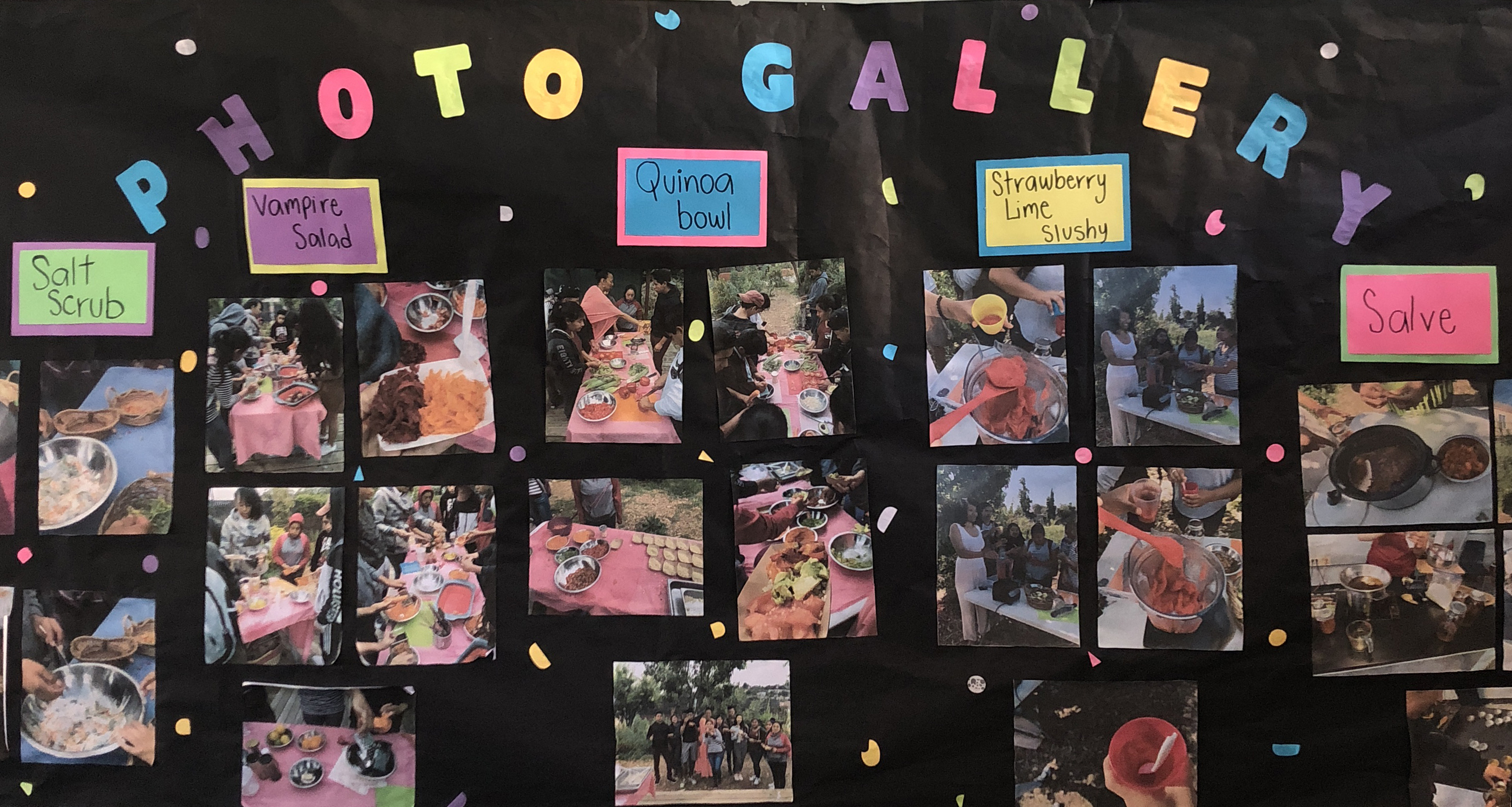

As I read the final sentences of their project-based essays, I realized why I became a teacher. This moment erased all of the stress I had experienced from trying to provide my 13 to 17-year-old students with meaningful and effective classroom experiences while resources were cut year after year from an already bankrupt district. Instead, this moment replaced that stress with an infinite amount of hope and endurance. We were doing our final presentations, which were a culmination of the previous six weeks of studying indigenous forms of healing. Over the course of the unit, we had listened to three guest lecturers. A colleague came and talked with us about the Dakota Access Pipeline, showing us a slideshow with video footage of their experience in South Dakota. We welcomed a Ph.D. student from UC Berkeley, who shared audio of her work in gathering oral testimonials from Peru’s Amazonian medicine doctors. We also engaged with a local advocate for land and cultural reclamation, who shared pictures about the history of land colonization in the Americas before we planted our own non-GMO seeds and made indigenous foods in the campus garden.

The students I work with are all Newcomer students, meaning they are recently arrived refugee students who came to the U.S. within the last three years. Many of our students arrived less than a year ago and have little to no English language skills. They are below grade level in literacy and have never seen, let alone used, a computer before. While the multimedia formats of our guest lectures may seem basic as someone who grew up with access to computers since childhood, over the course of the visits I realized just how impactful the video, audio and visual imagery was for my students. They were able to see and hear from places as distant as the Amazon, from centuries past and from various perspectives. Many of our students of Mayan descent shared about the confidence they gained in doing this project. They appreciated the technology, which gave them witness to the effect of indigenous healing through plant-based medicine, strengthened their ties to the land and cultural practices, and gave them comfort in being seen.

The final project included an in-class, 30-minute group presentation along with a final essay that described the unit and how it affected them. Students had a choice to present on the themes of indigenous food, oral testimonies or visual representations, all by integrating either a google slides or poster presentation and including photos. After a full week of supporting the technological aspects of students’ presentations, I began to wonder if I was asking too much of them. Some of the students were also in my elective computer class, so I expected them to be able to integrate the use of cameras and other audiovisual equipment to finalize their projects. However, for students in other classes (including some of my most recent students who may have arrived in the last few weeks), I began to wonder if I was creating a system of disadvantage and inequity. How could I require their presentations use technology if some students had never even seen a computer before?