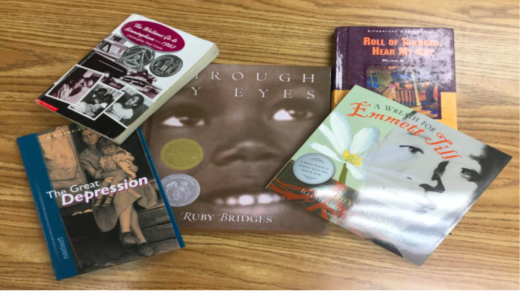

The Adventures of Huck Finn (Disney, 1993, Rated PG): Set in the South during the 1830s, a young boy learns the consequences of lying, the meaning of loyalty and the importance of liberty for all, as he helps a runaway slave escape along the mighty Mississippi River.

Seabiscuit (Universal/DreamWorks, 2003, Rated PG-13): Set before and during the Great Depression, this incredible, inspirational tale about a jockey, a trainer, an owner and a horse, all who literally beat the odds, will have students alternately cheering and weeping.

The Untold Story of Emmett Louis Till (Velocity/Thinkfilm, 2006, Rated PG-13): Director Keith Beauchamp’s acclaimed and influential documentary about the torture and lynching of a Northern black boy who dared to whistle at a white woman in 1955 Mississippi.

The Long Walk Home (Dave Bell/New Visions, 1990, Rated PG): Set in 1955 in Alabama, a white privileged housewife eventually breaks with her family and friends to support her black maid’s participation in the Montgomery bus boycott.

Ruby Bridges (Disney, 1998, Rated TV-PG): Set in 1960 in New Orleans, an exceptionally bright first grade girl breaks a color barrier and teaches her family and community a lesson in fortitude and forgiveness that is utterly unforgettable.

Sins of the Father (FX, 2002, No rating: language, adult situations, violence): Alternating between the past and the present, this film features a determined FBI agent and a now-grown-up, conflicted boy who ensured that justice is served some thirty years after four little girls were murdered.

Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner? (Columbia Pictures, 1967, not rated): Set in San Francisco in 1967, a liberal couple’s convictions and long marriage are put to the test when their daughter’s fiancé teaches two sets of parents the glory of love.

Preparing to Teach Films

- Parent Permission: At the beginning of every school year, it is wise to get parent permission for all of the movies you plan to show your students. Consult your school district’s policy for showing films, and send home a letter for parents to sign and return that outlines the movies you intend to show this year, including the movie’s MPAA rating and its instructional merit.

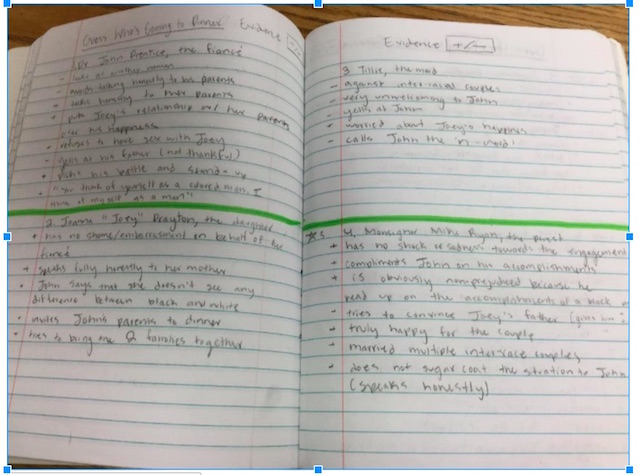

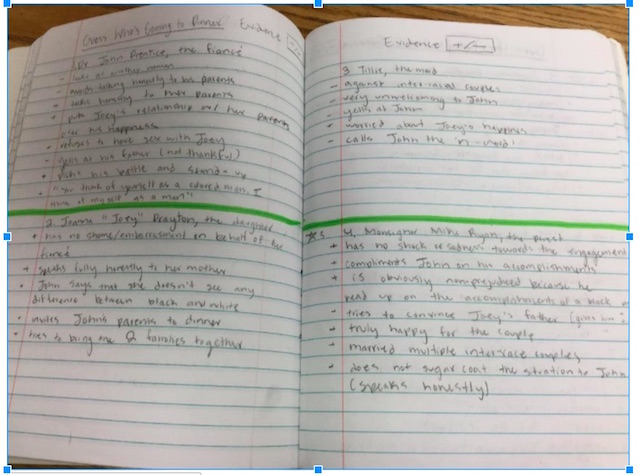

- Character List: Look up the cast list for all movies on IMDb. Compile a list of the major characters in a movie, giving students the first and last name along with a brief explanation of who each character is. My students take notes during movies, with half a page in their notebooks devoted to each important character.

During the Movie

- A Communal Experience: Just as I always prefer to have whole-class novels read entirely while in class, I want the viewing of movies to be a communal experience. We are not merely studying these films, my students are collectively living these journeys with the characters in real time. I do not flip the learning of movies by having my students view them beforehand at home. I want us gasping, laughing and sobbing as one!

- Note-Taking: I require my students to take notes during every movie. I keep enough light on in the room so students can see what they write. Since I do not want students watching two screens at one time, these notes are always written on paper. This way, when students later compose their essays on a computer, they can easily access their handwritten notes. Depending on the topic of the upcoming essay, students document relevant evidence from the movie beside the appropriate character’s name. Students are responsible for their own notes, but I do pause the movie at important junctures to ask questions, conduct short discussions and clarify confusions.

[media-credit id=11405 align="alignnone" width="640"] [/media-credit]

[/media-credit]

- Honoring the Art: Even though I pause each movie several times, I do so judiciously and only when it does not interfere with the flow of the plot. Clarifications and conversations may be necessary at certain points, but I always wait until the arc of the current action has subsided. This policy also holds true for when I choose to stop the reading of class novels in order to discuss the finer aspects of the work.

Multitude of Sources

By adding narrative and documentary films to my repertoire of historical sources, I provide my students with a rich and varied experience that goes beyond the printed page, requiring them to listen carefully and watch attentively. In this way, my students become increasingly savvy and sophisticated in their interactions with media.

Editor’s Note:

[/media-credit]

[/media-credit]