I teach creative writing to transitional English students at the college level, as well as to English language learners in the upper elementary grades. Regardless of which age group I’m working with, my biggest challenge is teaching revision. I know how I would revise a student’s draft, but simply communicating my own ideas about next steps for a piece in progress is not the same as teaching students to synthesize and implement revision strategies independently. For some students, feedback and suggestions in the margins are enough to get them on track (i.e., “Add sensory details here.”), but others need more visual graphic organizers to guide them. For these students, Google Docs tables can function as quick and sturdy — but removable — scaffolds that bring structure and focus to their writing as they sculpt and fine-tune their work.

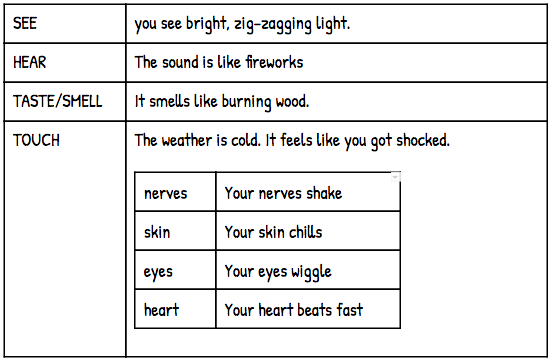

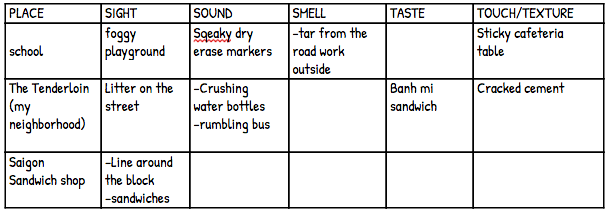

Sensory Maps

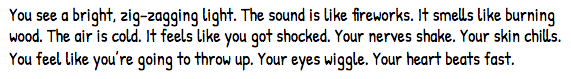

Although “show, don’t tell” is the writing teacher’s mantra, sensory details are often absent from students’ early drafts where the goal is “getting it down” — the plot, gist, idea — in broad brush strokes. At this early stage, I encourage students to follow the draft wherever it leads them. When they get to a stopping place or an “I’m stuck” or “I’m done” moment, I ask them to break their piece up into chunks, moments or scenes by hitting enter a few times in between sections. In each new space, they add a table to serve as sensory map to the section beneath it where they will zoom in on details that “show.” For students who struggle getting even a first draft down, I keep a link to an empty sensory map on a Google doc, like this one, in the About section of my Google Classroom. Students can open this document, go to File>Make a copy then add details to their copy of the table.

Student Example: Fiction

Below is an early draft of the opening of a superhero story by a fourth grade student writer named Daniel. This excerpt, like many early student drafts, is all “telling” about a pivotal moment the author must “show” in scene.