This term, I’m working on methods to squeeze the words out of my reluctant writers. Imagine a tube of oil paint that has a little dab left inside. How to do you get the final valuable bit of paint out? Just like your toothpaste you squeeze it. You apply pressure, you flatten the tube, and roll the ends up. This is the image comes to my mind when I am struggling to get my students to write about art. Obliviously, I can’t use pressure tactics to get students to write about their art, so I employ a stealth approach to engage students in the necessary critical thinking needed to devise a successful art essay, artist statement, or critical analysis.

Since developing proficient writers is my goal. I had to figure out where to start. First, I review the Visual Arts Vocabulary, so that students have the words to match to their beginning art projects. KQED’s The Elements of Arts videos and the Principles of Design provide further foundational concepts and vocabulary for communicating about art which we emphasize when discussing student work and images from art history. Additionally, changing art bulletin boards frequently generates discussion among students. Students look for their own work to be displayed and by viewing other students work they naturally start to use their new vocabulary to appraise, compare, and justify their artwork within their thoughts. Ideas and new questions emerge when students examine other students’ solutions to an art theme or problem.

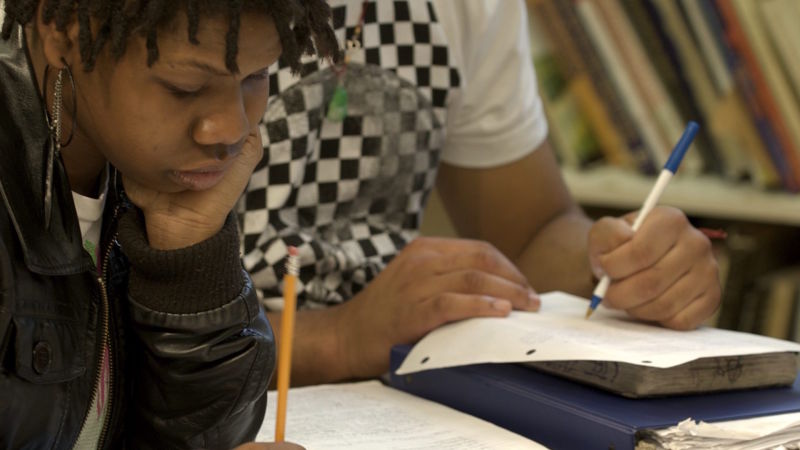

Typically a frequent reaction to a writing assignment is student despair. Comments like, “Is writing necessary in art?” or, “The ART speaks for itself!” come tumbling out of my quick-witted students. Even though the information is inside them, writing about their thoughts on art seems paralyzing to my students. Frustration overcomes many creators when asked to defend their artwork with written words. As a response, I’m in the habit of throwing out several puzzling questions to get my students thinking. If the message isn’t immediately clear, how do I decipher the meaning? Are there visual clues that show a connection between the artist and viewer? How do I discover the meaning or story in a work of art? Is my reaction to the art influenced by personal bias, life experience, prior knowledge or cultural norms? What do you think the artist’s intentions were? How do we know? Does my perception of the art work differ from the artist’s intentions? Then, using the question frame “I wonder if _____________?”, I ask students to formulate their own questions about viewing art. Developing thoughtful questions and seeking multiple answers will support students in critical thinking, which in turn will lead to reflective writing.

Observation skills are key to drawing and also to viewing art. As a teacher I often guide students in seeing detail in nature and art. Teaching students to look carefully helps students appreciate the world around them. However, “looking” is not a simple task. Seeking out complexity and emotion in art is many layered endeavour. Developing observations skills will also help students write with confidence. Students that learn to describe an artwork by making lists, soon have words to compose an essay. Students who generate questions will also find engaging art themes to explore in their writing.

A simple classroom exercise is to present students with an image and ask them to list everything they see. Select artwork relevant to your student population. My favorite images come from surrealist artists such as Rene Magritte and Salvador Dali, street murals, and local living artists. Go for complex images, more detail allows students to do an indepth investigation of the artwork. Then proceed to a pair-share, students can compare lists and see the different items or ideals that a partner might have found. Next have partners formulate a list of 10 items; starting with the focal point to a minute detail and write their list on the board. Allow a few minutes for introspection before conducting a discussion. Hopefully students will find ideas that they can apply to their writing. Repeat this “Observe and Describe” activity 3 to 6 times during a semester for best results.