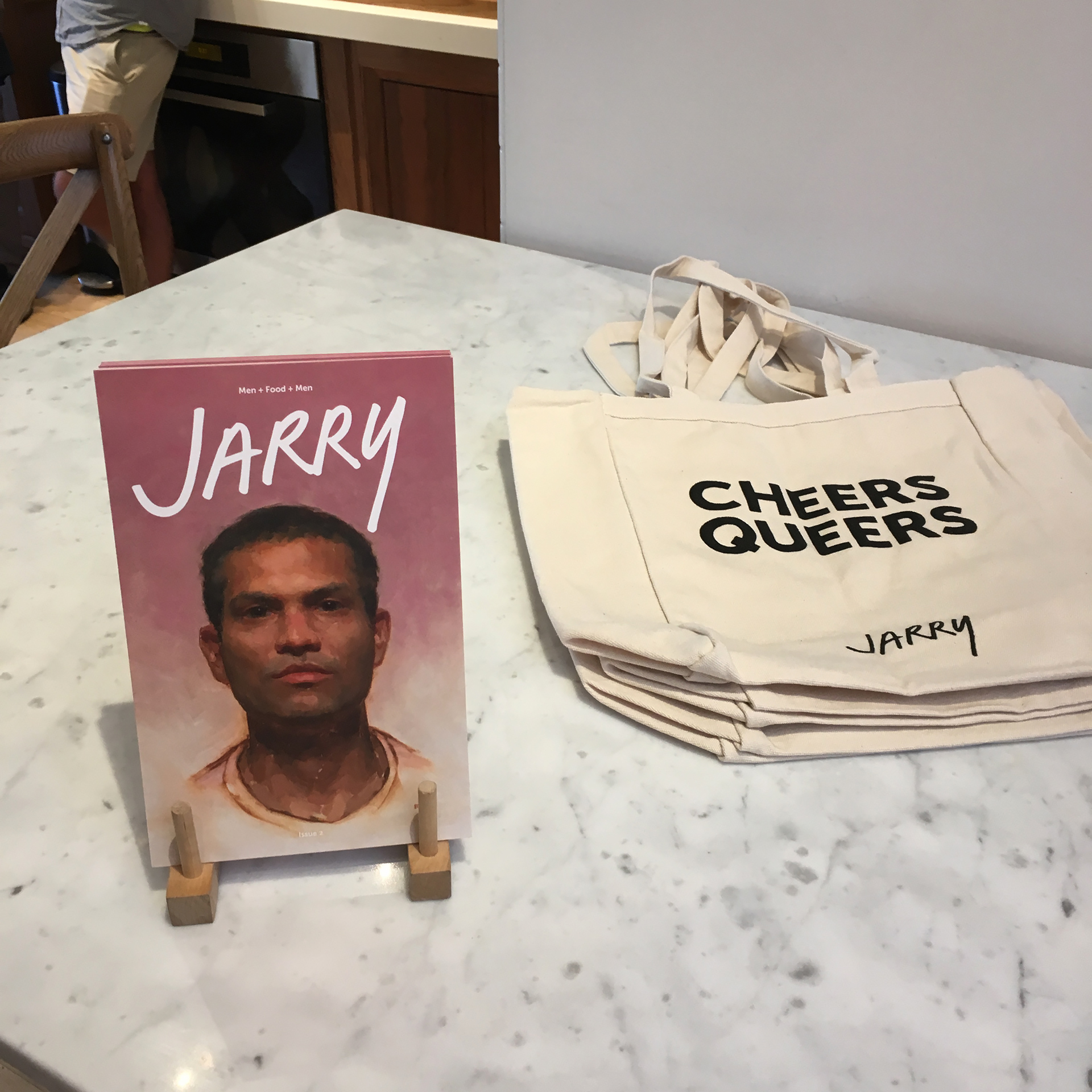

What is a queer kitchen? Is there a recognizable queer style or sensibility that can be expressed through food? Can non-gay chefs queer their food? As the rainbow-stickered crowds in booty shorts and body glitter surged through Dolores Park and Civic Center on a sunny Saturday afternoon, a rather more sedate audience of thirty gathered upstairs at Williams Sonoma's flagship store in Union Square to listen to a discussion of these questions and more. The conversation was the first San Francisco event organized by the New York-based gay men's food magazine Jarry, a twice-yearly print publication that launched (thanks in part to a Kickstarter campaign) in the fall of 2015.

According to moderator (and Jarry co-founder/editor) Lukas Volger, the idea of the "queer kitchen"--as opposed to "gay food"--seemed both more inclusive and more contemporary, at a time when few, if any, restaurants would position themselves as catering to an exclusively gay clientele.

Writer and former chef John Birdsall is a firm believer that there is a queer aesthetic in food, with its roots in the work of Craig Claiborne, James Beard, and ex-pat Richard Olney, a trifecta of closeted gay men whose sensibilities and far-reaching influence changed the way Americans cooked. It's a legacy that Birdsall thinks more people--especially straight chefs--should acknowledge. "I love Lucky Peach [magazine]," said Birdsall. "But the first couple of issues were really reflective of that male, straight, bro-y chef culture." It was this narrowly macho focus that led Birdsall to set the record less than straight with America, Your Food is So Gay, which won a James Beard Journalism Award in 2014. Birdsall, now 56, remembers he and a boyfriend reading aloud from Olney's writings, feeling like they were getting a glimpse of a secret gay world, one that was, by necessity, elusive, both cooly cerebral yet infused with the sensuality of Olney's adopted home in the south of France, its brilliant light, its hillsides of thyme and lavender.

But what was coded and discrete before was, by the 1990s, exploding into we're here, we're queer, get used to it, especially in San Francisco. When Preeti Mistry, co-owner and head chef of Oakland's Juhu Beach Club, first came to San Francisco in 1996, she found out lesbians like Elizabeth Falkner, Traci Des Jardins, and Elka Gilmore putting their stamp on the evolving California cuisine of the time. Mistry, who originally wanted to be a filmmaker, was inspired by these chefs' creativity and fearlessness, so much so that she left a job in the "gay bubble" of Frameline to start training in fine dining at Claridge's in London.

"These women were my heroes," she said. It wasn't just that these women were out, at a time when restaurant kitchens could still be tough places for women, gay or straight. It was that they were changing the game, on and off the plate. "At Citizen Cake, Elizabeth changed the presentation of pastry," said Mistry. Her cakes were architectural, pierced with sugar shards or kitschily frosted shag-carpet deep. They were disruptive, deconstructed, even a little bit dangerous. (It's no surprise that her first cookbook, written in the form of a comic book, was titled "Demolition Desserts.") Mistry remembers a dinner with Jim Dodge, then a well-known pastry chef trained in a more classical style. "When Elizabeth's dessert came out, he said 'What is this crap?'" It was a clash of sensibilities, his gay, hers queer.