Nor that the U.K. banned these food additives in 2008—a move that led to the reformulation of many products also sold in the U.S. The companies also fail to mention that recent studies suggest many children may be consuming far more dyes via the foodand drinks they consume than previously thought.

FDA: ‘Food Coloring is Safe’

So why are American children eating far more artificially colored food than their European counterparts?

First, when a company like Mars says “artificial colors pose no known risks to human health or safety,” it is largely reflecting what the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has said. “Color additives are very safe when used properly,” Linda Katz, director of the FDA’s Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition Office of Cosmetics and Colors, said in a statement on the FDA website.

While the FDA considers all substances used to change the color of food “additives,” the colors in the hot seat are nine synthetic dyes derived from petroleum rather than plant-based materials. These dyes show up on ingredient labels with names that include FD&C Blue No. 1, FD&C Yellow No. 5 and 6, and FD&C Red No. 40. Their approval by the FDA dates back to the 1960s, 70s and 80s.

And the agency must “certify” each “batch” of one of these dyes before it’s approved for use. In addition, the FDA must approve any new food coloring additives before they go on the market. That said, all but two artificial food dyes now in use can essentially be added to any and all food.

Kids Are Eating Much More Food Dye Than You’d Think

Based on experiments done with lab animals, the FDA set what it calls “acceptable daily intakes” in the 1960s, 70s, and 80s, based on how many milligrams of a dye is safe to eat in a day based on human body weight.

For example, the average 65-pound child would have to eat 150 mg of Yellow No. 5, to exceed this recommended limit. This probably isn’t a problem if they eat only one serving of a food that contains the dye. But even if that child stays away from brightly colored foods like popsicles and candy, the milligrams can add up quickly.

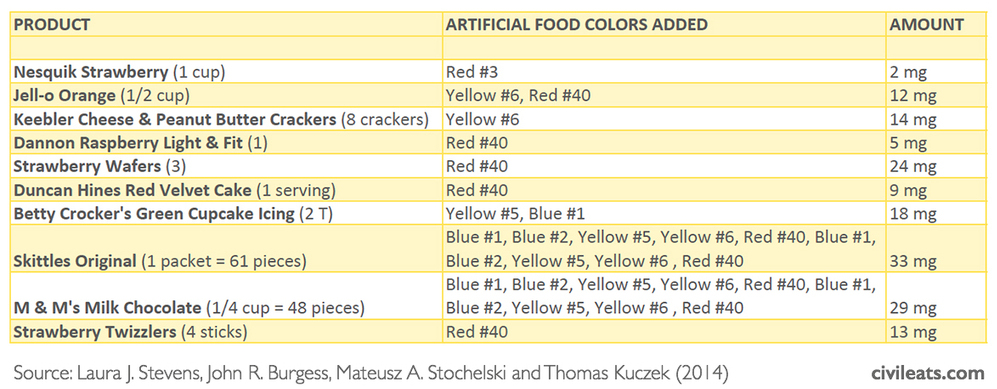

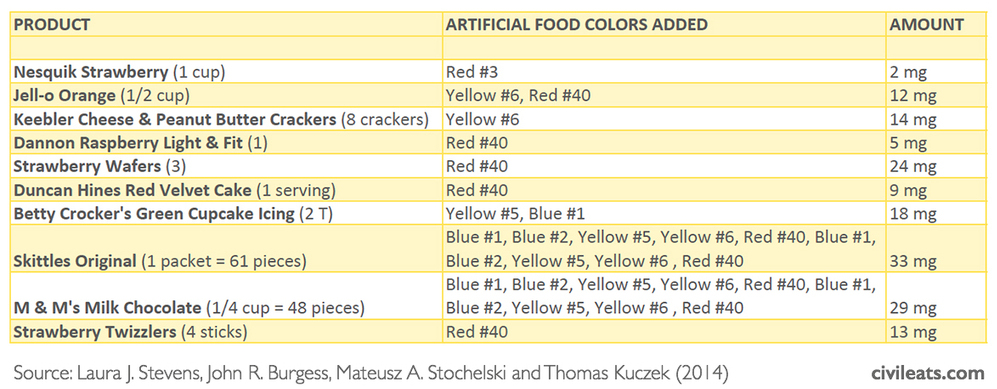

According to data compiled by Perdue University Department of Foods & Nutrition researcher, Laura J. Stevens and colleagues, a serving of Apple Jacks (10 mg), a packet of peanut butter cheese crackers (15) and a cup of cherry Kool Aid (52), a serving of Hamburger Helper (8), a couple tablespoons of colored salad dressing (5), two cups of orange drink (41), and three strawberry Twizzlers (13), plus a few Vlasic pickle slices would put the child over the 100 mg mark.

“We don’t really know for sure exactly how many children are being affected,” says Stevens, referring to hyperactivity caused by food coloring. But the numbers are not insignificant. Studies looking at this connection have found that, nearly 90 percent of children tested had adverse reactions when they ate 100 mg or more of these colors. And around 8 percent of all U.S. children—or almost 6.4 million as of 2011—are estimated to suffer from ADHD symptoms that Stevens says may be exacerbated by food dyes.

In 2011, the last time the FDA convened a formal committee to review the science on these colors, it concluded that for “certain susceptible children,” behavior problems might be exacerbated by synthetic colors. In other words, explains Center for Science in the Public Interest (CSPI) senior scientist Lisa Lefferts, “Even the FDA concedes that some children are sensitive.”

But because the agency couldn’t prove a definitive causal link—absolute cause and effect—between these dyes and behavioral impacts, it recommended more study rather than precautionary action.

CSPI recently released a report called “Seeing Red,” which takes the FDA to task for failing to take decisive and precautionary action on food dyes and for failing to set protective enough safety limits. “The underlying science has not been critically re-examined with reference to health outcomes that include behavioral impacts,” says CSPI director of regulatory affairs Laura MacCleery.

What’s come to light in the past 15 years, CSPI points out—including the studies that prompted regulatory action in Europe—has not changed regulations created here several decades ago.

Meanwhile, whether they acknowledge the links to behavior problems explicitly or not, food manufacturers worldwide are responding to consumers who are voicing their preference for food without artificial colors. In fact, a 2014 Nielsen global survey found artificial color to be the third highest consumer concern when it came to food and health.

So what’s a parent to do? “[Food coloring] is hard to avoid entirely so it’s a matter of minimizing,” says MacCleery. “Kids are getting way too much,” she says so “anything you can do to reduce this, they’ll be better off.”

Key to doing this is reading labels, since even the food manufacturers who have decided to eliminate these FD&C colors, are still in the midst of changing their ingredients. “You have to read every label,” said Stevens. And for those tempted by “red velvet” cupcake recipes? Try one made with beets instead of Red No. 40. Or this one MacCleery recommends, which calls for red wine.