The Bay Area’s love affair with ice cream has a long history. In 1928, an enterprising soul invented the It’s It ice cream sandwich and sold it at San Francisco’s Playland-at-the-Beach, and it soon became a Bay Area icon. Swensen's and Mitchell’s ice cream parlors have battled it out for ice cream parlor dominance since the 1950’s, with each attracting a loyal following. And now, there’s ice cream of every style and flavor available, whether you’re craving a simple scoop of ube, or a creamy cup of salted caramel created with liquid nitrogen.

The Bay Area also happens to be the birthplace of another frozen treat: the Popsicle. In 1905, 11-year-old Frank Epperson mixed some sugary soda powder with water and left the mixture out overnight. (Epperson’s location is debated: some sources, include his Associated Press obituary say he grew up in San Francisco, but others say he lived in Oakland). It was a cold night, and the mixture froze. In the morning, Epperson devoured the icy concoction, licking it off the wooden stirrer. He declared it an Epsicle, a portmanteau of icicle and his name, and started selling the treat around his neighborhood.

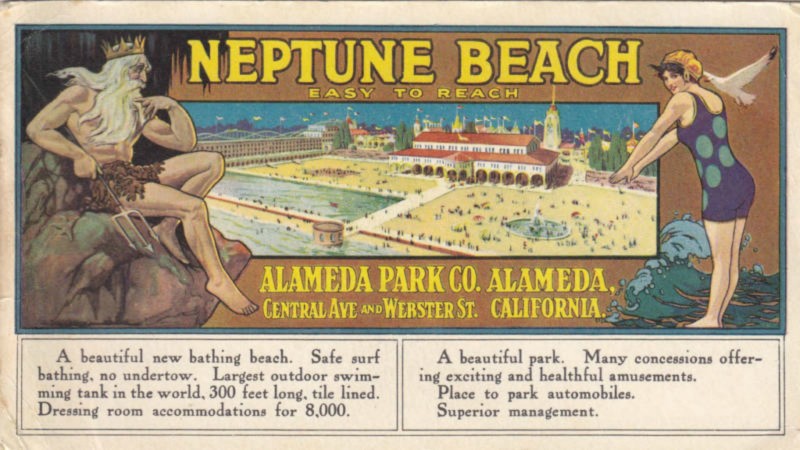

In 1923, Epperson decided to expand sales beyond his neighborhood. He started selling the treat at Neptune Beach, an amusement park on the coast of Alameda. Dubbed a “West Coast Coney Island,” the park featured roller coasters, baseball, and an Olympic-sized swimming pool. Neptune flourished in the pre-Depression days, and consumers eagerly consumed epsicles and snow cones (which also made their debut at Neptune).

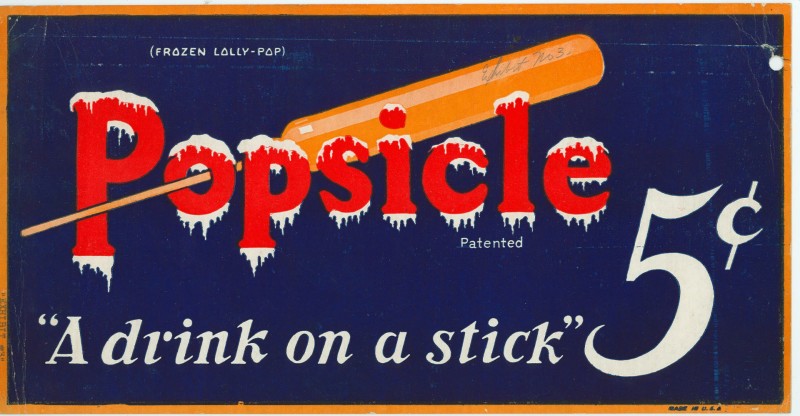

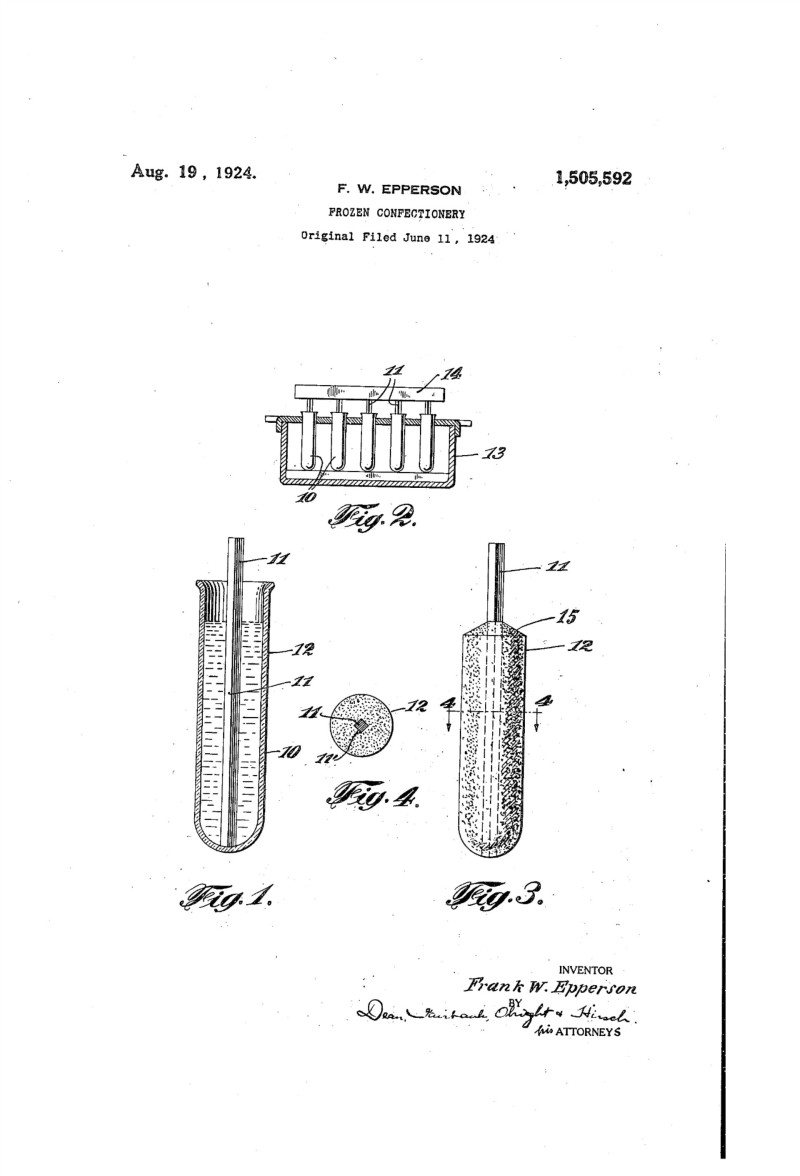

Buoyed by this success, Epperson applied for a patent for his “frozen confection of attractive appearance, which can be conveniently consumed without contamination by contact with the hand and without the need for a plate, spoon, fork or other implement” at the Oakland courthouse in 1924. The patent illustrates the requirements for a perfect ice pop, including recommendations on the best wood for the stick: wood-bass, birch, and poplar. Eventually, Epperson’s children urged him to change the ice pop’s name to what they called it: a Pop’s ‘Sicle, or popsicle.

Epperson’s charming yet unverifiable origin story has since become a quaint urban legend, but it didn’t have a happy ending for the inventor. A broke Epperson sold the rights to his creation to the Joe Lowe Company in 1929, much to his regret: "I was flat and had to liquidate all my assets," he later said. "I haven't been the same since."