Food is attached to the environment, food is attached to health, food is attached to labor, food is attached to social justice, income inequality, it’s all there. Forgive me, but you’re an idiot if you think you can think about food in a vacuum without thinking about those other issues.

And then it becomes a political question. Who do you think this country should be run for? I think this country should be run for the benefit of the majority of its people. It’s not being run that way right now. When it is, some of these problems will have taken care of themselves. Sometimes we’re talking about food, and sometimes we’re talking about the bigger picture. Social justice. Democracy. Government. Capitalism.

You’ve said that we’re focusing on the wrong kind of agricultural research--what should we be looking at instead?

The focus on ag research for the last 50 or 75 years has all been about yield. We’ve proven that we can grow a lot of corn, and we’ve proven that we can do really amazing things with increasing yield. But that’s not what it’s about. We need to grow food that has minimal impact on the environment--that’s probably not compatible with thinking that yield is the most important thing. We need to grow food that is fair--that may not be compatible with increasing yield. We need to grow food that’s not poisonous--that's probably not compatible with yield. Let’s back up a little bit and ask different questions. Let’s pretend we don’t know as much as we do and say, “If we were starting again, how would we grow food? What would make sense?”

You touched on this in your recent editorial with Michael Pollan about a national food policy.

Suppose we started with the notion that food that is sustainable, nutritious, fair and affordable [should be] available to everybody in the United States. It’s not a ridiculous thing to say. It’s actually quite primitive, really. We don’t say that. But if we did say that, how would we then go about fulfilling that mission statement? Suppose we make that our mission statement. I don’t know how we get to that place, but it doesn't mean we shouldn’t be asking those questions.

What would it take to get there?

Well, if Obama was a progressive as we thought he was in 2008, and if there had been a cooperative congress all the way through--it might have happened. Maybe he should have pushed it in 2008 when there was a more cooperative congress. I think what it takes is a well-intentioned president, a well-intentioned Congress, a not-stacked Supreme Court. It’s a lot. It may not happen in my lifetime. It may not happen in your lifetime. But that is the goal.

We can all make changes in our own lives, we can all eat better. We can shop at farmers' markets, we can talk about this stuff until we’re blue in the face. We can convince all our friends to eat well, blah blah blah--that’s change, that’s for real.

But there's some change that’s going to have to come from the top down. You need agencies that don’t have revolving door policies so that you have principled people running agencies. You need to have courts that understand that when an agency makes a decision, it’s a well-intentioned decision and the industry shouldn’t be able to challenge every single thing that affects them and so on down the line. When do those stars align?

I feel like in every interview I wind up saying “We're not patient enough.” And the fact is, I have to remind myself that I’m not patient enough. I think change should happen more quickly, but I’ve thought that my whole life, and now I’m 65 years old.

Some changes happen quickly. I think it’s a less racist country than it was 40 years ago, it’s a less sexist country than it was 40 years ago, it’s certainly a less homophobic country than it was 40 years ago. Those are amazing changes, right? And if you’re a woman or a black person or a gay person, you might think well, not soon enough. It’s not for me to say, I’m none of those things, but what I can say is that I’ve seen a lot of change, and now we’re seeing change in food.

And really, the food thing, this conversation, is only--when was Omnivore’s Dilemma published? When was Fast Food Nation published? This conversation is only 10, 12 years old, and it’s been a broad conversation for only five years.

What’s stuck out to you as a turning point in this conversation? Has it been a bunch of small changes or one big change?

Labor has really stuck out for me. The fact that people who cared about food did not talk about labor five years ago and now they do talk about labor, that’s a big deal.

What do you think caused that change and awareness?

You can shame people and say “You talk about animals all the time but what about humans?” Even if humans are just animals, why would you care more about the cows than the people in the slaughterhouse? Why would you care more about the lettuce than the farm workers? I think people started to get that. I did write a column, I don’t think it was a very good, but it was an interesting notion: I wrote a column about redefining the word “foodie” and what people who express an interest in food ought to be interested in, and how that has changed.

You didn’t ask me what I had for lunch. You’re not talking to me about how great the food is in Berkeley, have I been to Oakland and eaten at blah blah blah, what my favorite restaurant is in San Francisco or how cool the farmers' market is and all the great stuff you can buy there even though it’s January. We’re not talking about that. We’re talking about the politics of food. That’s incredible. Five years ago, we would not be having this conversation. That’s a big change.

You talk about all these insurmountable issues--what makes you optimistic?

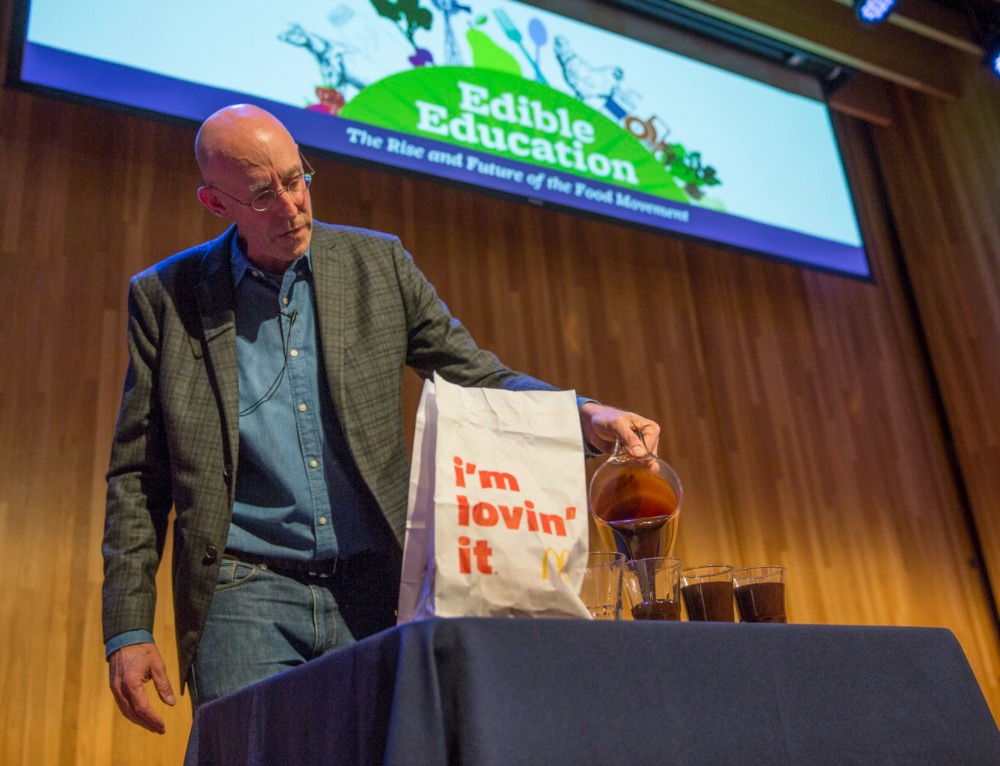

Wendell Berry said “Don’t be optimistic, be hopeful.” What’s changed? Many things have changed for the better. McDonald's lost a ton of money this year already, farmers' markets are still on the upswing, people talk about food in a way that they didn’t used to talk about it, there’s a lot of changes.

You've mentioned the new food policies by countries like Greece and Spain and--what, if any, countries are doing it “right?”

No one’s doing it “right.” Mexico has a national soda and junk food tax, that’s pretty cool. Brazil has a kind of right-to-food statement, that’s pretty cool, but it hasn’t fulfilled it, so that’s disappointing. I’m not aware of anyone who's doing it right.

And besides, this is America. It’s unlikely we’re going to mimic anybody. A problem is that we’ve set a bad example in many ways and other countries have followed it. We have shown how bad food can be. We have shown how unhealthy food can be. If you wanted to devise a really bad diet, you couldn’t do a much better job of doing that than we’ve done unintentionally. I think eventually that will change, but it may change other places more quickly than it changes here.

At the 2014 New York Times Food for Tomorrow Conference, you said that we have enough food to feed the world (view speech). So what should we instead be talking about when addressing hunger and access issues?

It’s money that’s the problem. It’s not a food issue; it’s a justice issue. You have never seen a hungry rich person and you never will. You’ll probably never be [hungry]. I never will either. Because we’ll have 20 dollars in our pocket. If we’re hungry we’ll go buy something to eat. There is enough food. It’s just a money question.

The Bay Area has a notable amount of food deserts--for example, just a few miles away from where we are in Berkeley, with its farmers' markets and numerous grocery stores, there are parts of West Oakland that don’t have access to anything like that. What are some ways to combat those kinds of discrepancies?

What about using schools as distribution centers for subsidized fruits and vegetables? Many people have children, and they go to schools. If you don’t have a child, you could still go to the school. There’s a school in every neighborhood. Neighborhoods are not school deserts; no one calls them school deserts.

I mean if you’re talking about a desperate situation--people can’t get healthy food--we are paying, and I don’t say this begrudgingly, but we are paying for the costs of people eating bad food. We call that health care costs. You get sick when you eat bad food. You’re paying one way or another, so why not pay for prevention instead of cure? Especially since the cures don’t work. And the way to pay for prevention is to guarantee that people can eat decent food.

In the short term, some people are going to suffer. Nothing I can say can change that. I can’t come up with some hocus pocus “You can cook a mixture of water and cement and it turns into a good dinner."