As a longtime food writer and former restaurant chef, Slater has a savvy savory palate that can dip into the herb-and-spice pairings of cuisines around the world and translate them, deliciously, into satisfying, boldly flavored dinners without seeming dilettantish. He pairs green salad with peaches and ham, and mackerel with gooseberry sauce. Guinea fowl is roasted with figs, a Chinese-style pork roast is glazed with plum-ginger sauce, and apples accent pheasant, duck, blood sausage, and rabbit. Turkey gets a stuffing of apricots and pistachio; pork goes with peach salsa, blackberry-and-apple sauce, pears, quinces, plums, even rhubarb.

When it comes to sweets, however, he’s a home cook, still with an English schoolboy’s love of the crumbly and the comforting. Not for Slater are the more contemporary, multi-layered (and quite delectable) concoctions found in books like pastry chef David Lebovitz’s Ripe for Dessert.

Instead Slater, growing preciously small backyard amounts, keeps his preparations full-flavored and unfussy. There are rough-hewn galettes, juicy deep-dish pies, and nearly two dozen easy, buttery, not-too-sweet cakes, weighted with nuts and fruits, gently spiced, equally good as a breakfast nibble, a teatime pick-me-up, or a family dessert.

The fig chapter has five variations on figs baked with wine, sugar, and spices, while berries are paired with cream in everything from tiramisu and panna cotta to a raspberry-ripple yogurt fool and a frozen ice of raspberries and cream. Of a peach melba-ish summer fruit sundae (peaches poached in vanilla syrup, served over ice cream and drenched in raspberry-red currant puree) he writes simply, “Oh, joy of joys, such greedy bliss!”

However much he may enjoy summer’s peaches, he saves his most finely wrought enthusiasm for the less obvious pleasures of the autumn and winter table--its apples and quinces, pears and walnuts. I cannot think of another food writer who has penned such rhapsodies in honor of the baked apple and its sweet, buttery-topped sister, the apple crumble. While many of the cold-weather, elegantly named heirloom varieties of apple (like D’Arcy Spice, Orleans Reinette, Ribston Pippin, and Cornish Gilliflower) that Slater espouses are rarely seen in the Bay Area, his enthusiasm should encourage you, come fall, to seek beyond the easy Fuji and Galas to the more complex, older apples like Esopus Spitzenburg, Ashmead’s Kernel, or Cox’s Orange Pippin.

As with Tender, however, the real reason to add Ripe to your cookbook shelf is Slater’s smart, supple prose and tart observations, which are at once lyrical, deeply felt, and irresistibly irreverent. Nowhere is this better illustrated than in his introduction, as he writes,

There is a moment, sometime around the middle of September, when this garden, this diminutive hortus conclusus I have made in an 1820s London terrace, truly becomes the garden of my dreams. The leaves are turning from green to gold, amber, and rust, the last of the fruits hang crimson and smoky blue on the trees, the pumpkin-colored dahlias and Michaelmas daisies have collapsed like drunks across the gravel path. The garden darkens to the color of ginger cake, here and there a shot of saffron, brilliant ochre, or deepest crimson. The colors, I guess, of the Vatican at prayer.

The last berries, apples, and plums, wet and almost rotting from the late sun and autumn rain, lend a mellow, alcoholic scent to the space, like the dregs of an abandoned glass of wine. The garden is falling asleep with an air of damp tobacco and wood smoke, but it is still abundant too, with late blackberries, damsons, and a grapevine at breaking point. Each year I race to get to those blackberries before the feast of Michaelmas, when the devil is said to piss on them.”

Recipe: Crisp pork belly, sweet peach salsa

Ask your butcher to score the skin finely for this, as the crackling is essential. The first brief roasting at the higher temperature sets the crackling on the route to crispness. These ribs are not sweet and sticky like the ones in The Kitchen Diaries, but lightly crisp and lip tingling.

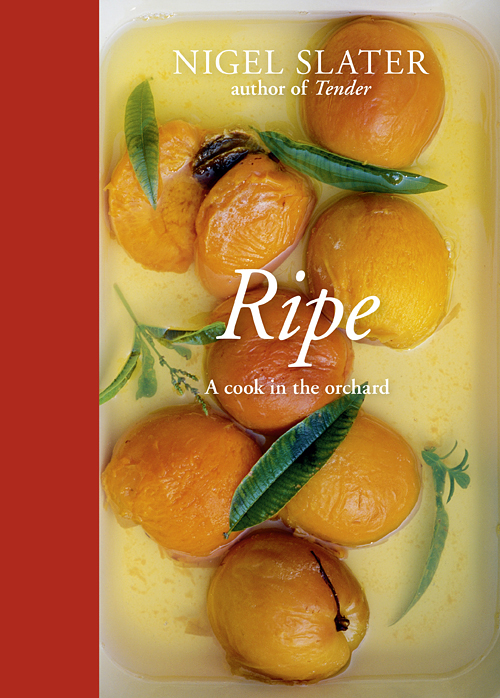

Adapted and reprinted with permission from Ripe: A Cook in the Orchard by Nigel Slater, copyright (c) 2010, 2012. Published by Ten Speed Press, a division of Random House, Inc.

Ripe: Crisp pork belly, sweet peach salsa. Photo: Jonathan Lovekin

Yield: 4 servings

Prep Time: 30 minutes, plus 4 hours' marinating

Cook Time: 1 hour to 1 hour 10 minutes

Total Time: 1 hour 30 minutes to 1 hour 40 minutes

Ingredients:

Pork belly – 2 to 3 pounds (1 to 1.5kg), boned, skin intact and finely scored

For the rub:

garlic – 3 cloves

light soy sauce – 2 tablespoons

peanut oil – a tablespoon

salt – 2 teaspoons

dried chile flakes – half a teaspoon

Chinese five-spice powder – a slightly heaping teaspoon

For the peach salsa:

green onions – 2

a small red chile

peaches – 3

cherry tomatoes – 8

cilantro – a small bunch

juice of 2 limes

olive oil – 3 tablespoons

Preparation

1. Put the pork in a china or glass dish. Peel and crush the garlic to a paste, stirring in the soy, oil, salt, chile flakes, and five-spice powder. Spread this paste over the skin and underside of the pork and leave it to marinate for a good four hours, if not overnight.

2. Preheat the oven to 425°F (220°C). Place the pork in a roasting pan, then cook, skin-side up, for about twenty minutes.

3. Lower the heat to 400°F (200°C) and continue cooking for a further forty to fifty minutes, until the skin is dark and crisp. Leave to rest for ten minutes before carving.