As he went through his patrol training, Cantú watched as his body became a tool. But his resolve to experience the border was unshakeable. Once, during shooting practice, as a bird landed on his target. He shot at the bird wanting to prove to himself that he could take a life: “I walked over and picked up its body and in my hands the dead animal seemed weightless,” he writes. “I rubbed its yellow feathers with my fingertip. I began to feel sick and I wondered, for one brief moment, if I was going insane.”

He dug a small hole to bury the bird. The beauty of this memoir is that Cantú remains sensitive and discerning even while he is undergoing the transformation into an agent. And yet the change is there, and it is chilling:

Of course, what you do depends on who you’re with, depends on what kind of agent you are… but it’s true that we slash their bottles and drain their water into the dry earth, that we dump their backpacks and pile their food and clothes to be crushed and pissed on and stepped over, strewn across the desert and set ablaze. And Christ, it sounds terrible, and maybe it is, but the idea is that when they come out from their hiding places…to find their stockpiles ransacked and stripped, they’ll realize their situation… that it’s hopeless to continue, and they’ll quit right then and there, they’ll save themselves and struggle toward the nearest highway or dirt road to flag down some passing agent…—that’s the idea, the sense in it all.

But still, I have nightmares, visions of them staggering through the desert, men from Michoacán, from places I’ve known, men lost and wandering without food or water, dying slowly as they look for some road, some village, some way out. In my dreams I seek them out, searching in vain until finally I discover their bodies lying facedown on the ground before me, dead and stinking on the desert floor, human waypoints in a vast and smoldering expanse.

At the border, Cantú encounters drug mules, and he hears of migrants who’ve been kidnapped by their smugglers until their family pays extortion. He encounters children, teenagers, couples, desperate to provide a better future for their children, desperate to reunite with loved ones. He encounters migrants who’ve ran out of food and have collapsed, dead, in the desert.

During the downtime of patrol nights, Cantú observes the beautiful display of the desert’s inhospitality: the ground seething “with volcanic heat,” the glittering Milky Way above, and sometimes in the distance, lightning “like a line of hot neon, [illuminated] the desert in a shuddering white light.”

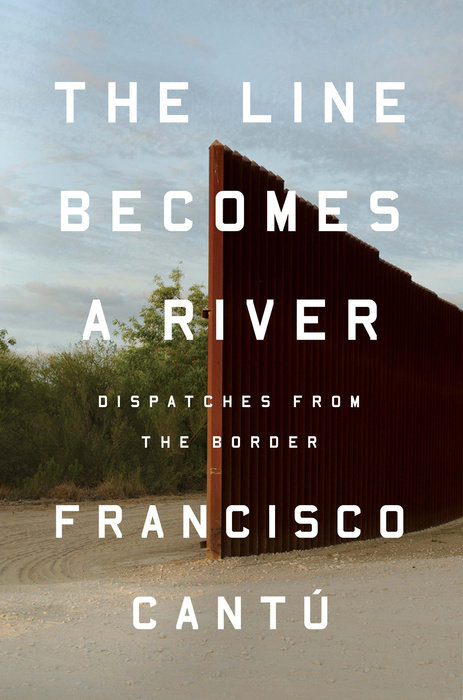

After quitting the Border Patrol, Cantú finds himself courting yet another aspect of the border. A friend who is undocumented is deported, and Cantú spends much of his time trying to help the family that the border has torn apart. The driving question of this memoir is whether one can be absolved of complicity, and if not, whether there is a place where one can hold that place of guilt. For readers, The Line Becomes a River, offers a unique but hard look at what the border is really like, both for migrants and the people in charge of deporting them.

In this memoir, Cantú cites the poetry of Sara Uribe:

Count them all.

Name them so as to say: this body could be mine.

The body of one of my own.

So as not to forget that all the bodies without names are our lost bodies.

It occurs to me this book tries to do just that: It attempts to count, it attempts to plea for all the lost bodies. The Line Becomes a River is a powerful, harrowing view of the border — a no man’s land where no one returns the same.

Run, don’t walk, to your bookstore.

Francisco Cantú will be in conversation with R.O. Kwon at Green Apple Books (1231 9th Avenue in San Francisco) on Monday, February 19th at 7:30 p.m. More information here.

The Spine is a bi-weekly column. Catch us back here in two weeks!