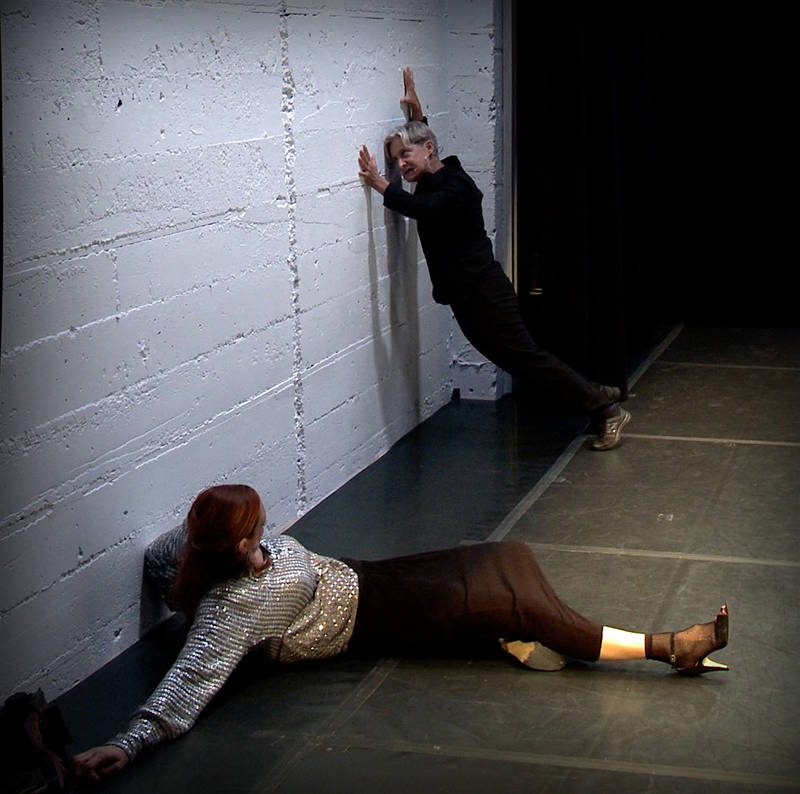

Hope Mohr Dance’s 2017 Bridge Project opens with an unexpected scene: Monique Jenkinson, the first cisgender female to win a major drag pageant, dancing alongside acclaimed gender theorist Judith Butler as they share an “embodied conversation” beneath disco lights. Since 2010, Hope Mohr — the program’s artistic director — has organized the Bridge Project to interrogate a particular topic. This year, two weeks of interdisciplinary conversations, performances, and workshops will explore the idea of gender in movement and what it means to have a radical body.

“The Bridge Project was born out of a passion I feel to facilitate conversations in and beyond the dance world,” Mohr says. “It’s really important as dance-makers to be in conversation with people outside of dance. So I am trying to make those conversations happen.”

The project began with a focus on female choreographers, but has since expanded to challenge the “canon of modernism and postmodernism to include voices from historically marginalized communities,” in Mohr’s words. This year’s festival in particular is meant to unite artists, activists, and academics around the issue of gender equality — inviting performers to explore what it means to have a radical body through their respective mediums.

And, with a program that features academics and performance groups, this year’s Bridge Project makes that goal a reality. Take, for example, the festival’s eclectic opening night. In their conversation, Butler and Jenkinson discussed — while dancing — how allowing the body to simply rest despite the demands of our productivity-driven society can be a radical act.

Butler’s comedic, quirky steps were the perfect foil to Jenkinson’s fluid modern movement. Through dance and rich conversation, the duo explored how just living, moving, and breathing in our current life conditions is a radical act — a body’s simple form of resistance to the oppressing forces of today’s world. By blending Jenkinson’s background in drag (a performance of femininity) with Butler’s academic approach, the performance offered a whole new way of understanding the body and how it can exist, radically.