At first glance, the Cantor Arts Center’s newest exhibition, Creativity on the Line: Design for the Corporate World 1950-1975 looks like a showcase of the hottest mid-century designers and the objects they spawned: Charles and Ray Eames’ pumpkin-colored fiberglass chair, Henry Dreyfuss’ Polaroid SLR camera, Dieter Rams’ 1956 Braun radio (so sleek it was known as “Snow White’s Coffin”). But the exhibition, as curator Wim de Wit says, is “more complex.” Digging deep into the relationship between designers and the companies they labored under, Creativity on the Line reveals the uneasy balance between visionary product design and corporate expectations, a tactic that simultaneously tempers the glamour of the objects on view and humanizes the people behind their sleek surfaces.

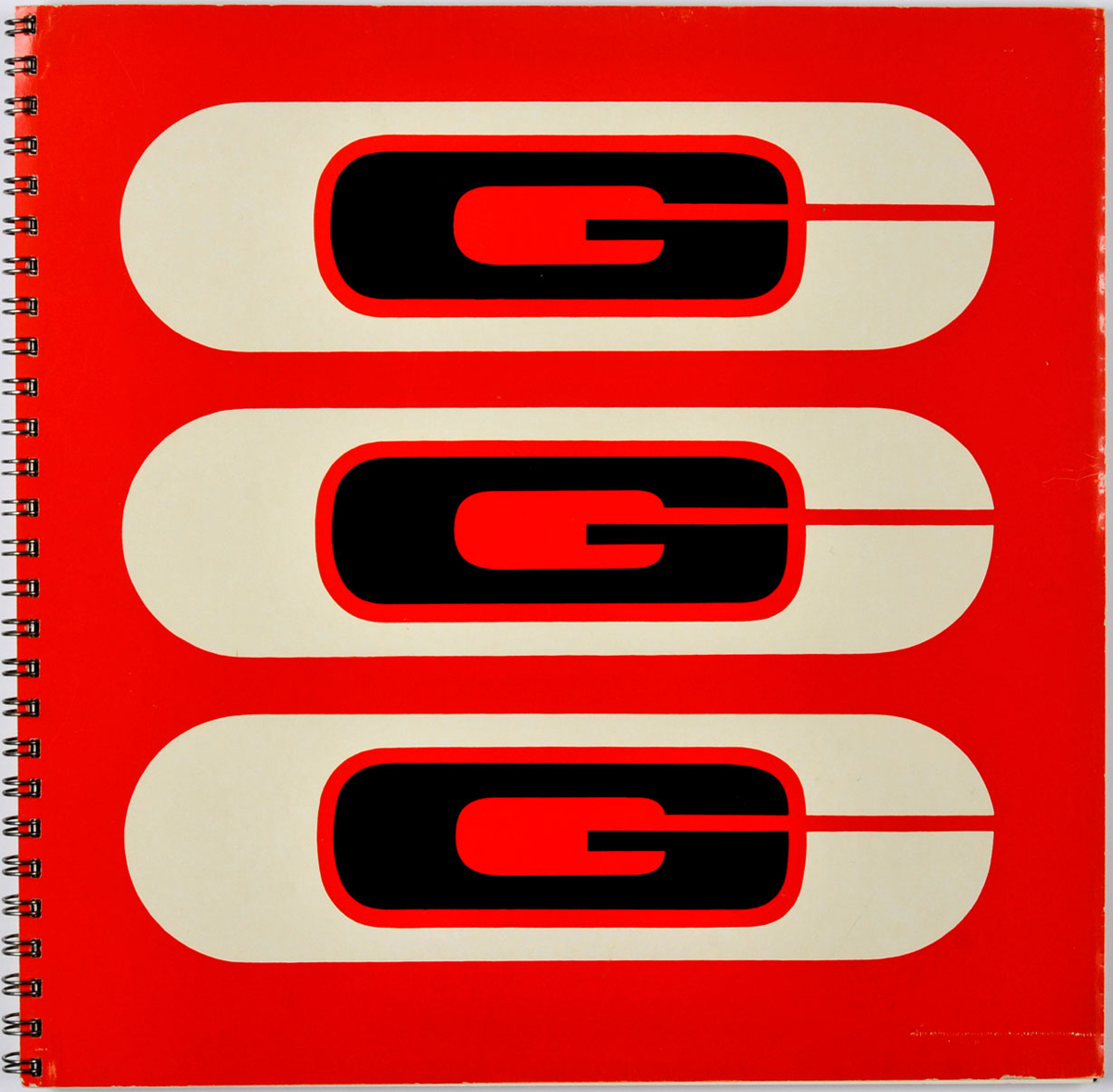

The exhibition design, borrowing from the time period it presents, presents consumer electronics, spiral-bound style guides and architectural models under plexiglas vitrines arranged exposition-like in an orderly grid. Tracing the history of designers’ involvement in corporate branding, product design and advertising, the arrangement of objects and wall text encourages a ping-pong movement between the walls, starting with Bauhaus influence on 1920s German design and ending, chronologically, with the first commercially successful personal computer, 1974’s Altair 8800.

Above the neat rows of vitrines, ambivalent and sometimes outright cynical quotes from prominent designers fill the far wall of the gallery. “We believed that once all business embraced the notion of design as a function of management, all of us would be employed to produce beautiful products,” says a quote from Saul Bass. “But it didn’t turn out the way we thought. Sure enough, Big Business embraced design, and promptly turned it into a commodity.”

This path from idealism to mistrust plays out similarly in the exhibition’s retelling of the history of the International Design Conference in Aspen. Inspired by his own company’s successful collaborations with designers and artists, Walter P. Paepcke, founder of the Container Corporation of America, launched the IDCA in 1951 to “promote better understanding and partnership between modern designers and representatives of the corporate world.”

But designers had other concerns over the years — in 1970 the conference almost ground to a halt when the counterculture (mainly environmentalists and architecture students from Berkeley and San Francisco, with a few French New Left activists thrown in the mix) showed up to protest the theme of “Environment by Design.” In a film documenting the conference, captured by Eli Noyes and Claudia Weill, speakers rail against consumer goods, question the legitimacy of a movement organized by white middle-class values, and point to the false dichotomy between humanity and the environment. Despite arguments that the conference was no longer relevant, the IDCA continued until 2004.

The insider view into a field rife with internal conflict continues in a section called “Most Advanced, Yet Acceptable” (MAYA for short), a phrase coined by American industrial designer Raymond Lowey. While companies hired designers to create aesthetically pleasing products — status objects and objects of desire — they didn’t want the products to surpass the limits of consumer taste.

Today, the 1961 IBM Selectric Typewriter on view in Creativity on the Line is a loan from the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. There’s no question it’s a work of great design, a revolutionary product both more efficient and more compact than its predecessors. But one wonders what shape this and other objects presented within the exhibition — and as a result, every product descended from them — might have assumed had the designers behind them been free of the imaginary concerns of a skittish consumer.