The San Francisco Museum of Modern Art recently sent out a survey. On one page, it asked, “Please select any artist whose work you would be interested in seeing in a special exhibition.”

Ignoring the woeful number of female and non-Western artists among the 18 options, only four living artists were included as practitioners whose work the public would theoretically like to see. Don’t get me wrong — like most, some my favorite artists are dead artists — but sometimes you want your visual culture to reflect the here and now, to come from a time and place that affects your own perception of the everyday, and challenges you to alter your view of the world.

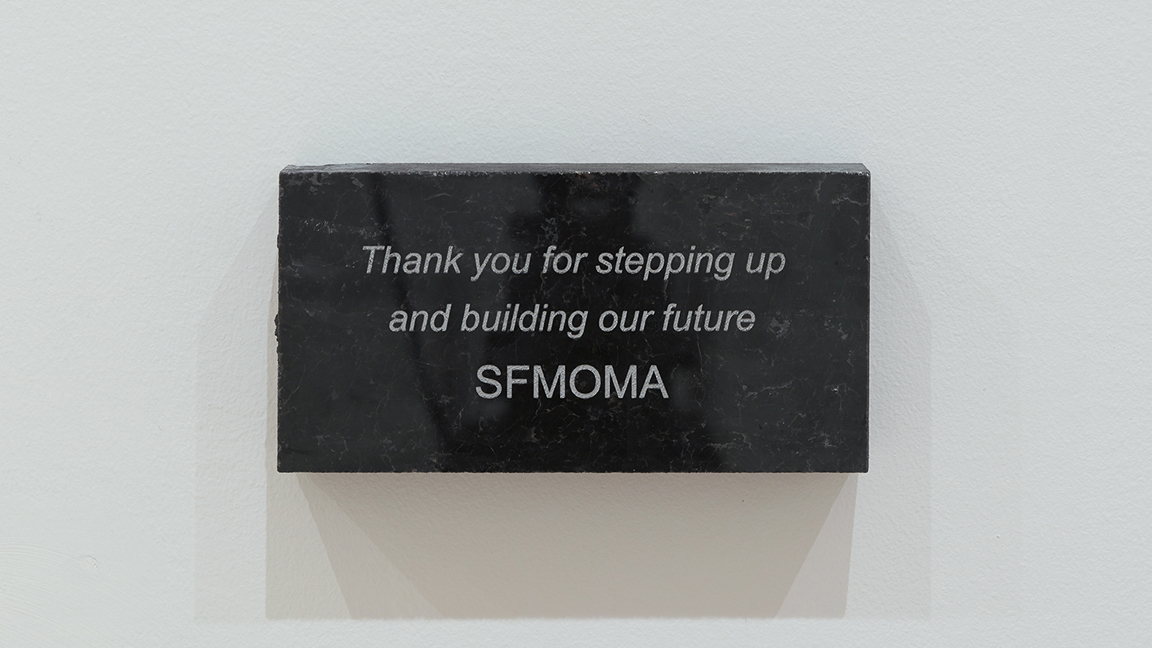

Thankfully, SFMOMA’s ongoing New Work series exists to show new bodies of work by contemporary artists in a dedicated gallery space on the museum’s fourth floor. The latest comes from New York-based artist Park McArthur: a group of photographs and wall-mounted sculptures that question the use and accessibility of public spaces — from highways to parks to campfires — and how language, through its presence or absence, creates social conditions in those spaces.

Twelve blank aluminum signs of varying shapes, the likes of which tell California drivers about areas of interest, recreation or cultural import, dominate the walls of the exhibition. Mounted back to back, half of the signs sit flush against the gallery walls. Up close and viewed from a stationary position, the anodized metal shapes become minimalist monuments stripped of their welcome messages, physically overwhelming next to McArthur’s small framed works.

The series’ title, Softly, effectively, references a statement from the Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices that imparts to roadside signs a sense of agency and civic pride: “As the direct means of communication with the traveler, traffic control devices speak to us softly, yet effectively and authoritatively.”