Jamaican poet and 2016 Whiting Award recipient Safiya Sinclair celebrates her poetry debut this month with Cannibal, a collection teeming with complex mechanisms organized around Shakespeare’s play The Tempest. The Tempest is Shakespeare’s shipwrecked tale: a duke is stripped of his station, put on a boat with his baby daughter, and beached on an island that he soon colonizes — killing the witch who rules the island, enslaving her son Caliban, and usurping their knowledge and magic.

The figure of Caliban as an enslaved indigenous person and as a representation of postcolonialism is the stuff of recent academic inquiry. After all, just as the original people of the Caribbean and South America and those brought there under enslavement were thought of as savage, backward, and barbarian, in The Tempest Caliban is described as a “freckled whelp, hag-born — not honoured with / A human shape.”

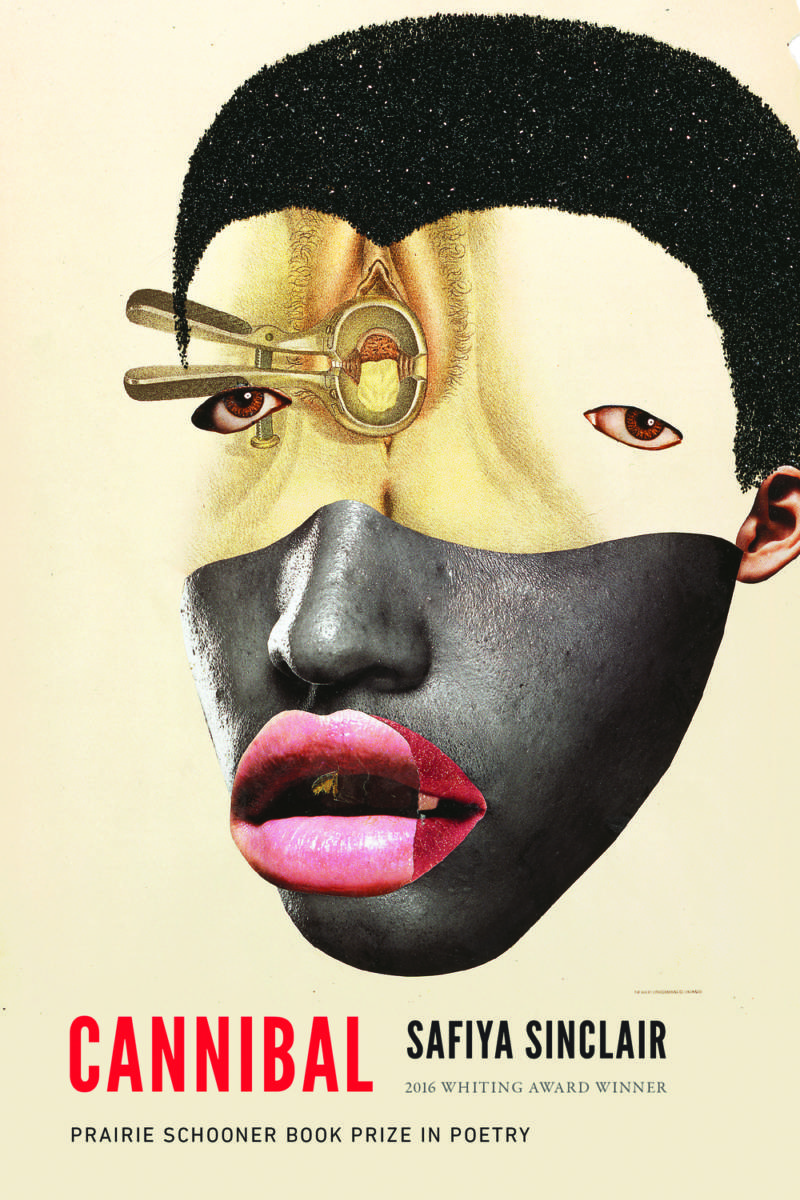

The fact that Caliban is an anagram for the Spanish canibal (read: cannibal) is not lost on Sinclair. In Cannibal the poet dresses herself in the white gaze that the portrayal implies. With a language beautiful, mythic, and hotly scorching, she inhabits a Caliban-like place until by the alchemy of reclaiming monster, reclaiming savage, reclaiming cannibal she comes upon a fearless fountain of power. Cannibal is provocative, occupying The Tempest in as subversive a way as you can imagine.

Here is Sinclair in “Crania Americana”:

Sibling, Sisyphean. Howl of my unusual,

now we have reclassified the very

ape of us.Half fish and Half monstrous.

Drowned spine of toothache take us

and barnacled, all crippled filaments

all jawbone […]Vexed skinfolk. Unfossiled, hence.

What a brittle word is man.

Self-inflammable, I abjure you.And wear your gabble like a diadem,

this flecked crown of dictions,

this bioluminiscence.Predator coiled eager at the edge

of these maps.Master, Dare I

unjungle it?

I met with Sinclair over coffee during her stopover in San Francisco as part of her book tour. “It’s like I have a bad affinity for Shakespeare,” she tells me laughing. “I can’t quit him.” Sinclair wears her leather jacket inside Four Barrel coffee in the Mission. She tells me that though she first identified with The Tempest‘s Miranda (the duke Prospero’s daughter), but once she arrived in the U.S. she began to identify with Caliban.