What is “music journalism,” anyway? Who does it serve? And what is its purpose in an age when consumers no longer need critics — nor record stores, for that matter — to discover new music?

I have been writing about music, in both amateur and professional capacities, for at least 16 years — which, as of this counting, is one-half my lifespan. I have been reading about music for even longer: one of my earliest, fondest musical memories is purchasing the Wax Trax! Black Box (a three-disc compilation cataloguing the hits on seminal Chicago electronic-industrial label Wax Trax!) as a barely pubescent tweenager and, seated in the back seat of my parents’ car, listening to all three discs in succession on my Sony Discman during a long road trip — reading voraciously the enclosed booklet all the while.

It was a meaty, detailed booklet, providing history and context for the artists included on the compilation. That was my earliest exposure to “music journalism,” writing which increased my appreciation and understanding of music beyond the mere “this sounds good” versus “this does not sound good.” (Not that those aren’t crucial criteria, of course.) But that booklet taught me about the artists and the culture behind the music: it taught me that when artists support each other, collaborate, and are propelled by like-minded record labels, genuine scenes are born.

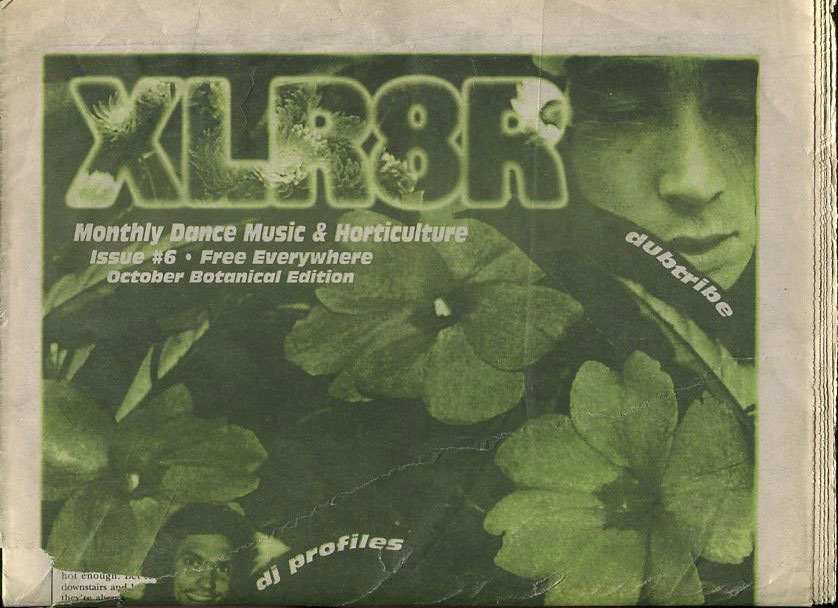

So it went in the ’90s and early ’00s — magazines like The Wire, XLR8R, URB, and others covered electronic and experimental music in print, while small, user-driven websites (like Brainwashed, one of the first outlets I published in) covered fringier material. As a music-discovery ecosystem, it functioned decently enough — listeners read about new music in print or online (increasingly online), then subsequently sourced said tunes by mail or at record shops, for those lucky enough to live in the proximity thereof. And then, by the mid-late ’00s, everything changed.