When Donald Trump was elected president, Oakland artist Lukaza Branfman-Verissimo wasted no time. Almost immediately, she grabbed a marker and a plain shirt and essentially created a wearable protest sign. It read, “PROTECT MUSLIM / LATINX / QUEER / BLACK / NATIVE / POCS / FRIENDS.” She took a selfie and posted it to Instagram. Not long after, the artist had created a digital poster that expanded her initial list to include “immigrant,” “trans,” “LGBTQ+,” “low income,” and “artist.” Soon enough, she was silk-screening posters and shirts for anyone interested.

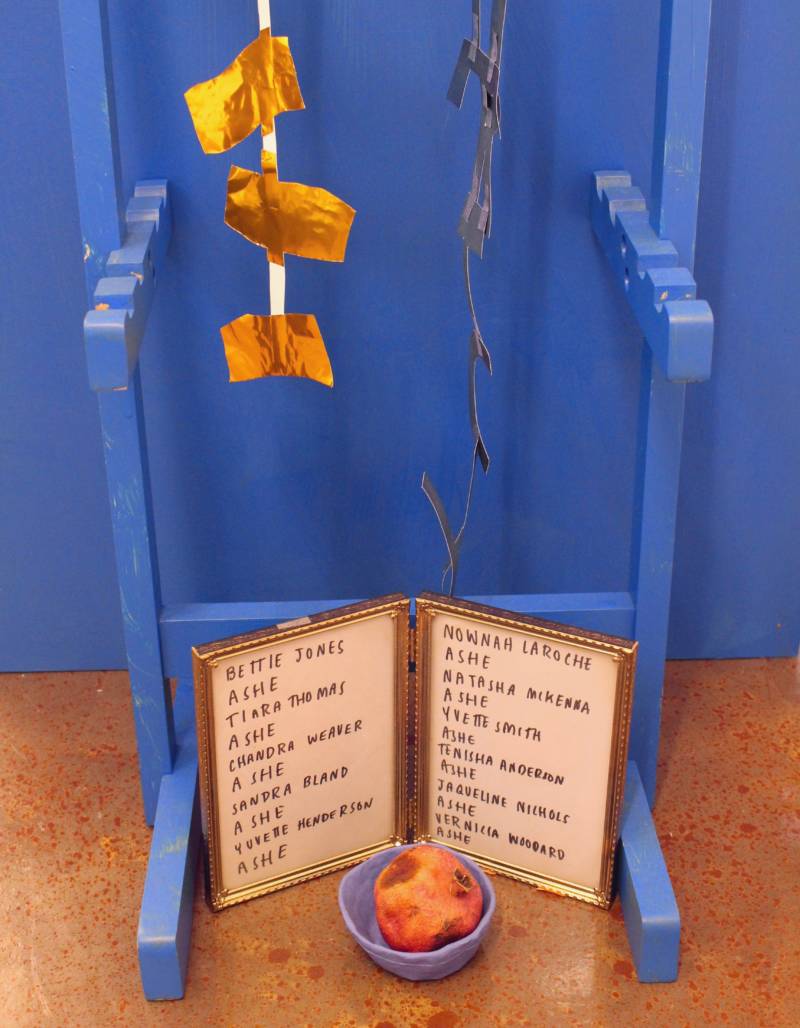

The Oakland artist’s work is typically based in social practice such as gathering people for conversations and collecting oral histories. At the end of 2015, for instance, she did a residency at E.M. Wolfman bookstore that involved hosting open listening sessions to hear people’s stories, then creating a collection of small found-object sculptures inspired by them.

But amid the recent political climate, Branfman-Verissimo has been increasingly interested in making signs. Being the Los Angeles-raised daughter of an Afro-Brazilian father involved in the Brazilian black power movement and a Jewish-American mother with familial ties to the communist party, protest signs are a familiar form, she tells me. But Branfman-Verissimo’s new body of work both champions and complicates the medium.

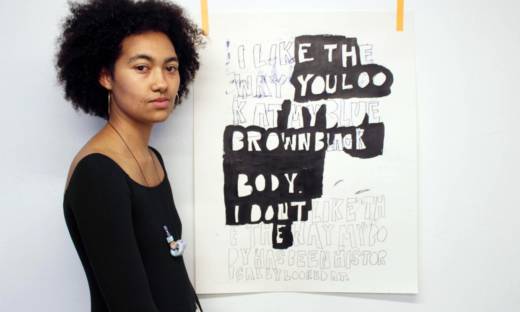

In her solo show, I like the way you look at my brown black blue body, I don’t like how my brown black blue body has been historically looked at, currently at the brand-new Lago Projects in Oakland, Branfman-Verissimo digs into the question of what it means to be a brown person in America today. As she puts it, the show is “thinking about brown bodies in my community of Oakland and nationally through examining my own self and looking at the dualities of being a mixed brown-black-white body.” And she does so, in part, through signage.