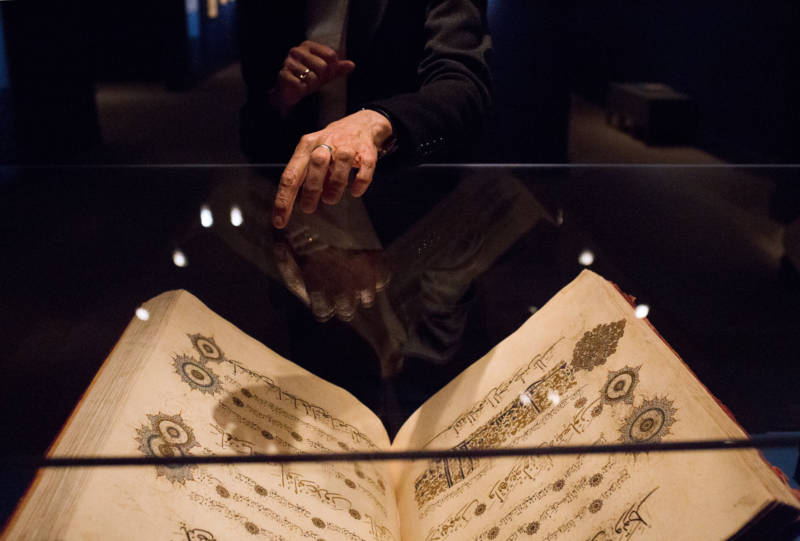

When you walk into the Smithsonian’s “Art of the Qur’an” exhibition, you’re met with a book that weighs 150 pounds. The tome, which dates back to the late-1500s, has giant pages that are covered in gold and black Arabic script.

“Somebody spent a lot of time, probably years, to complete this manuscript,” says curator Massumeh Farhad. “… The size tells you a great deal about it. I mean, clearly this was not a manuscript that could have been taken out every day for private reading. This was a manuscript that was intended for public display.”

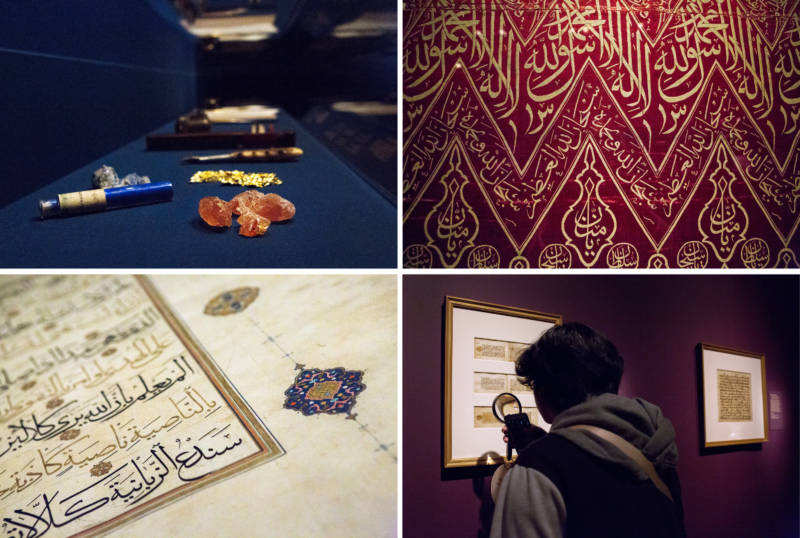

That manuscript is among more than 50 centuries-old Qurans on display at the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery in Washington, D.C. The exhibition isn’t about the words of the Quran so much as the people who laboriously copied the book, letter by letter. Some of their names are listed (one manuscript was written by a vizier, or prime minister, of the Ottoman Empire), but most of the creators are unknown.

Either way, each of the pages is one of a kind, and Farhad has flipped through all of them. She says it was a meditative experience: “You notice things that, you know, nobody else had noticed. For instance, human fallibility — because God is infallible but humans aren’t. So there are instances where the calligrapher omitted a verse, but then they always found a way around it. … They put a little asterisk where the verse actually fits in.”

In one Quran, that asterisk looks like an eyelash; it directs the reader to look for the missing verse on the edge of the page. In another, the writer corrected a wrong word by covering it with gold. “It’s the gold white out,” Farhad says.

The Quran copies are like little peepholes, allowing us to peer back into the lives of people we never knew. When Farhad flips through the books, she says she’s really flipping through the past. “And every page is absolutely breathtaking.”

9(MDAxOTAwOTE4MDEyMTkxMDAzNjczZDljZA004))