Ballet is a cruel business. After 10-15 years of monastic training, those few who win professional contracts face slim prospects of advancing from the corps de ballet to the rank of soloist. Even discounting the ever-present risk of a career-ending injury, dancers’ tenures tend to be brutally short. No wonder that so few of them feel they have the bandwidth to branch out into choreography –- at least, not until they have retired from the stage. And even then, companies rarely take a punt on the inexperienced.

Yet the ballet world direly needs fresh choreographic voices to boost demand for live performance. “Worldwide, the search for talented choreographers has become an important issue,” says Bolshoi Ballet spokeswoman Katya Novikova, admitting that the lauded Russian dance company has not built up as strong a pipeline of new choreographers as they would like.

This week, the industry has its eyes on Wei Wang. Trained at the Beijing Dance Academy and only in his third season at San Francisco Ballet, the 23-year-old corps de ballet member has just won a coveted promotion to soloist.

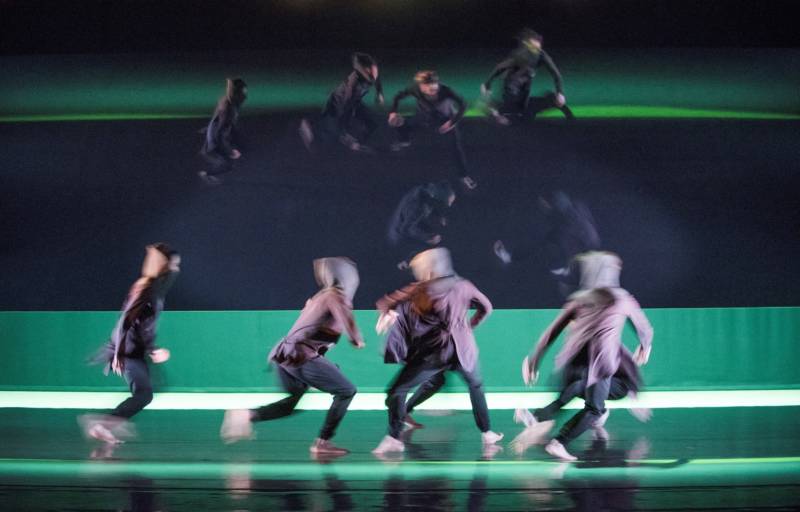

And earlier this week, Wang achieved a coup that lies well beyond the reach of most professional ballet dancers: he unveiled his first-ever choreographic work, created on advanced students of the San Francisco Ballet School, at the school’s annual showcase at the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts. Few other SF Ballet dancers have been been given the choreographic reins in the company’s long history. The very short list includes Myles Thatcher, James Sofranko, Francisco Mungamba and Benjamin Freemantle.

In Focus, Wang slices and engineers a recording of Beethoven’s Moonlight Sonata to incorporate street and industrial noises, as well as the sounds of rumbling thunder. Thanks to Jim French’s dramatic lighting design, the overall effect is gripping, like listening to the great composer’s music in a threatening storm. Later in the piece, the soundscape mimics being under the sea in a submarine, listening for the pinging of black boxes from a downed airliner. To this mercurial score, the very fine and committed quintet of Yumi Kanazawa, Shené Lazarus, Victor Prigent, Davide Occhipinti, and Nathaniel Remez slither, melt and twist their bodies into wondrous contours. The evanescent pairings, fluid yet sharply edged, are blessedly free of the romantic and sexual overtones that blight so many amateurish contemporary pas de deux. Wang presents each pair as a single organism.

Despite his lack of experience, the choreographer demonstrates a remarkable facility for movement invention, as well as a mastery of stillness and austerity. Will we be seeing more from this young man, who clearly has a lot to say?