Mothers, especially in America, can’t seem to catch a break. Let your child run wild in the woods or unchaperoned to the neighborhood market, and risk being arrested for neglect. Watch your child like a hawk, and risk accusations of helicopter parenting.

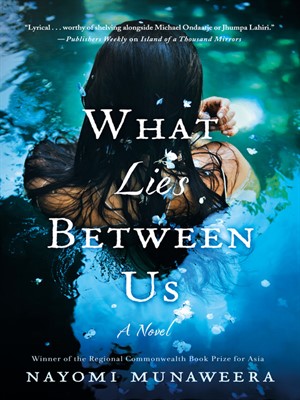

For these reasons, the opening lines of What Lies Between Us by Nayomi Munaweera gripped my imagination. Ganga, the novel’s narrator, is housed in a white cell painted an “industrial white.” The Sri Lankan-born American immigrant has done something “unthinkable,” an act that has made her the “worst thing possible,” a bad mother.

“But here’s the secret: in America there are no good mothers. They simply don’t exist. Always, there are a thousand ways to fail at this singularly important job. There are failures of the body and failures of the heart. The woman who is unable to breastfeed is a failure. The woman who screams for an epidural is a failure. The woman who picks up her child late knows from the teacher’s cutting glance that she is a failure. The woman who shares her bed with her baby has failed. The woman who steels herself and puts on noise-canceling earphones to erase the screaming of her child in the next room has failed just as spectacularly. They must all hang their heads in guilt and shame because they haven’t done it perfectly, and motherhood is, if anything, the assumption of perfection.”

Soon, we learn that Ganga’s crime is much more severe.

Before the details are revealed, the novel jumps into the narrator’s history, starting with her traumatic birth in Sri Lanka which left her mother unable to bear more children. Amma, Ganga’s mother, grew up in a poor household, but married into a wealthy, ancestrally important Sinhalese Buddhist family. Ganga’s reclusive but seemingly loving father is a professor, though he works out of choice and not necessity, and her mother swings between gushing, almost overbearing love for her only child and a violent need to be alone. Amma suffers from migraines and spends days shut away in her room; at other moments, she floats around the kitchen cooking lemon crepes and watching with delighted love as her daughter wolfs down her food.