Do you remember cutting paper snowflakes in school? Artist Rogan Brown has elevated that simple seasonal art form and taken it to science class.

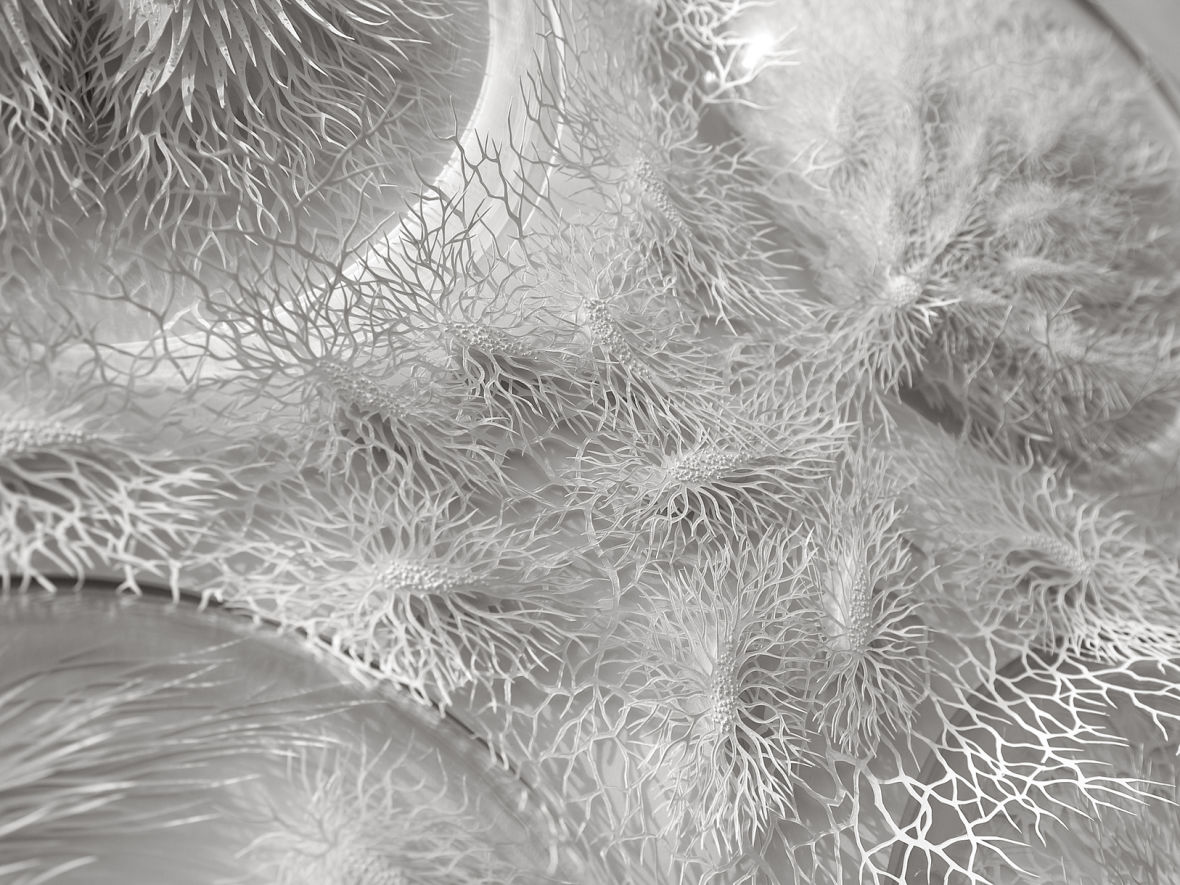

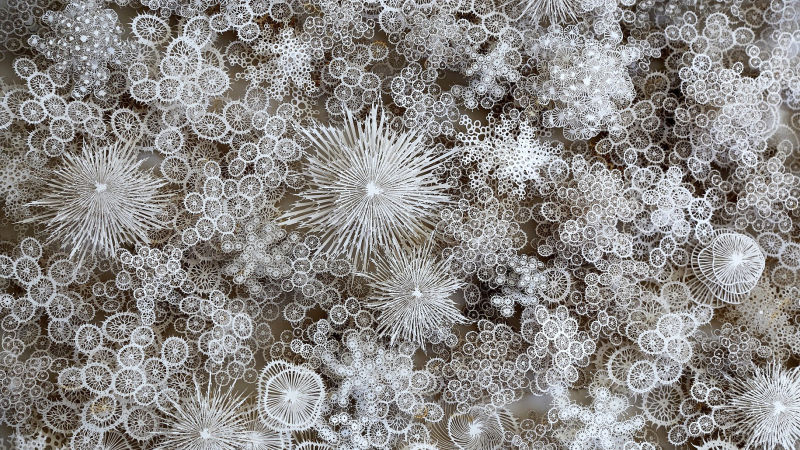

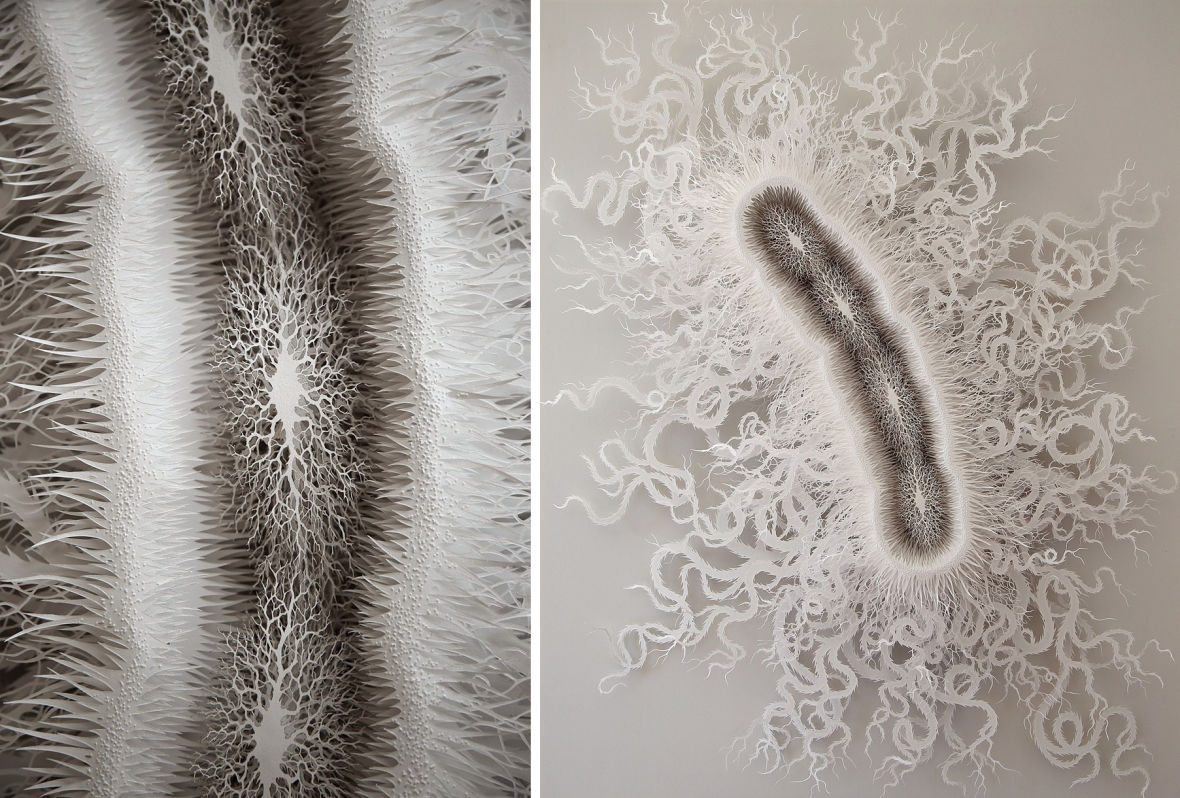

These large-scale paper sculptures may evoke snow, but actually trade on the forms of bacteria and other organisms. The patterns may feel familiar, but also a bit alien. You’re not looking at a replica of a microbe, but an interpretation of one. And that distinction, Brown says, is important.

“Both art and science seek to represent truth but in different ways,” the 49-year-old artist, who lives in France, tells Shots. “It’s the difference between understanding a landscape by looking at a detailed relief map and understanding it by looking at a painting by Cezanne or Van Gogh.”

Brown wants to you to feel something looking at these sculptures.

Last year, he met with a group of microbiologists to plan an exhibition on the human microbiome. He became fascinated by the hidden world of microbes and the strange shapes of pathogens. He was particularly interested in humans’ fear of the invisible microbiological world. That meeting led him to spend four months creating Outbreak entirely by hand.

He starts each construction by sketching detailed designs and then mocking them up in larger pen and ink drawings. Then he begins to think in 3-D. Each structure is composed of layers of paper, which are stacked using foam board spacers. This floating effect allows him to build a complex colony of organisms that appear to grow beyond the confines of their housing.

9(MDAxOTAwOTE4MDEyMTkxMDAzNjczZDljZA004))