Around a hundred people entered the upstairs reception hall at the Headlands Center for the Arts in Marin for cocktail hour last Thursday. A line started early at the bar. Everyone was eager to taste the specialty cocktails made for the occasion.

Vigorously shaking their concoctions, the bartenders draped freshly cut lace lichen in one drink, the pale green filaments undulating like seaweed in the bitters. They finished a second, sweeter one with a lemon verbena foam and fog-harvested water. Three flavors of popcorn were served up in movie-style brown paper bags: cultured dairy butter, fir tree, and sloppy joe military MREs (Meals Ready to Eat).

Despite all appearances to the contrary, this wasn’t an awards dinner for Bay Area locavores. Aeroir: A Taste of Place, as the event was dubbed, is part of the Headland Center’s ongoing programming around “a creative interpretation of place.” The happenings typically include talks by artists in residence and shared meals. Conceived of by a trio of confident, purposeful artists, Aeroir turned out to be a peculiar and disorienting amalgamation of taste and place, capped by an eccentric culinary performance art gesture aimed at raising environmental awareness.

Before the five-course meal, the organizers distributed several pamphlets and menus and repeated verbal instructions throughout the night to help the audience understand what Aeroir was about. “A Word on Aeroir,” the main program’s two-page preface, explained most succinctly how the intangible qualities of air and sky could be ingested and even appreciated by the human palate: “The act of consuming air through our digestive apparatus, rather than passively inhaling it through our respiratory system.”

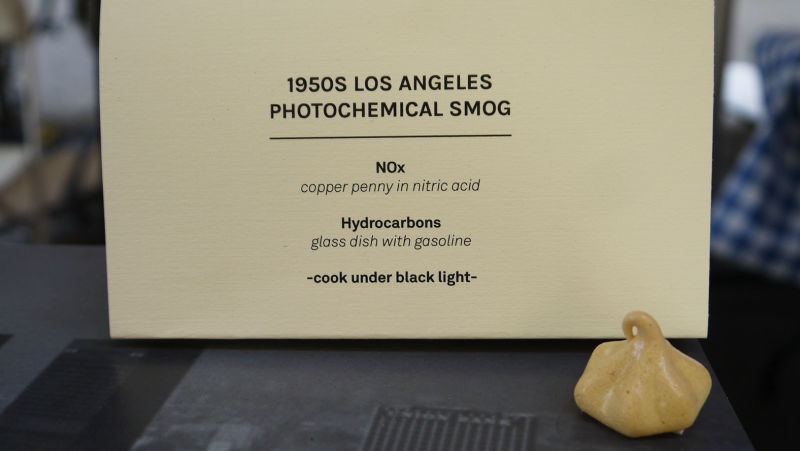

The waitstaff served up salt-baked beef, mung bean cakes, and bowls of mud-red cabbage soup with lemon foam and a soy-marbled egg to add flavor and pizzazz. But the main ingredient on the menu that night isn’t generally to be found in fancy restaurants, but rather in the air we breathe: smog.