Back to the Future, Part II

Written by Robert Zemeckis and Bob Gale; directed by Robert Zemeckis (1989)

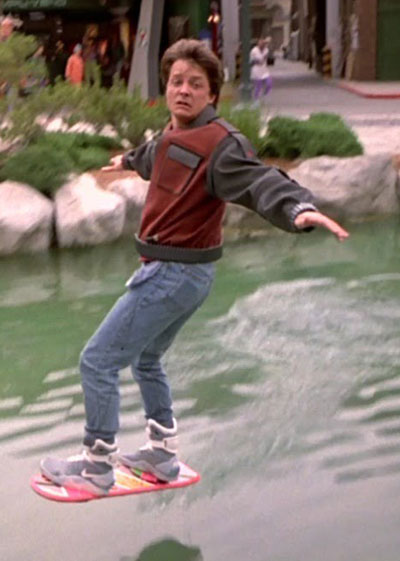

As much as I trend towards formatting these lists alphabetically by the author’s last name, this time we’ll go in reverse, in honor of the source of our skateboards. Since Back to the Future left off in basically the middle of the story, this part picks up shortly after the ending of Part I, and before you can say “Fasten your seat belt,” Zemeckis has transported viewers some 26 years into the future. As much as we may lament the absence of flying skateboards in our present (other than in this movie), Zemeckis and his team nonetheless did a good job crafting the atmosphere, if not the actuality, of today’s 2015.

Back to the Future, Part II shows a messy, dystopian America. And while the purveyors of the teen dystopian serials might have us think we’ve got it good, by many measures, we are living in a chaotic dystopia. And we don’t even have flying skateboards to compensate. Say what you will to the science fiction purity of this movie—it’s clearly a fun-filled fantasy—but Zemeckis and Gale took the pulse of 1985 and coughed up a 2015 that was highly entertaining, inspiring, even, and not without some prickly sharp observations of that which we’d prefer not to think about.

Rating: 10 Skateboards—Hang Ten. You can still watch this movie and make the bleak future they show a bit more fun.

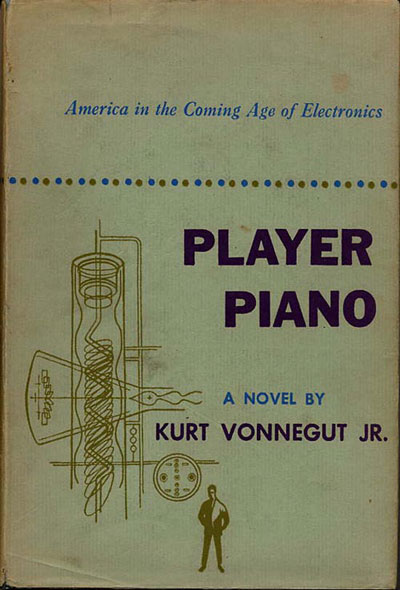

Player Piano

By Kurt Vonnegut (1952)

One of America’s great minds of the twentieth century began his career some 63 years ago with a novel set “sometime after a third world war.” This is a common call in early visions of the future, and quite important. It speaks to a deep-seated pessimism that colors how we see what is to come. But that’s not the worst part of the deal in Player Piano. Vonnegut, who wrote the book while he was employed at GE, was unfortunately clear on where technology was headed. In an interview about the book, he said, “Player Piano was my response to the implications of having everything run by little boxes. The idea of doing that, you know, made sense, perfect sense. To have a little clicking box make all the decisions wasn’t a vicious thing to do. But it was too bad for the human beings who got their dignity from their jobs.”

The boxes are smaller that Vonnegut might have imagined, but he’s got the income gap and the demolished middle class about right. He also treats all this with a foretaste of the mordant sense of humor that would infuse and inform his later works. Reading Player Piano today (and you should, even if they ditched the nifty jacket for the first edition), one can see just how much Vonnegut got so chillingly right. Oh, the details may be different, but the feel of America is here in spades. Toss in a subplot about a traveling Shah, and you have the perfect recipe for nightmares and laughter. The proportion between the two will depend on your place in the Luxury Gap.

Rating: Nine Skateboards. Ready for Maverick’s, Kurt!

Forty Signs of Rain, Fifty Degrees Below and Sixty Days and Counting

By Kim Stanley Robinson (2005-2007)

Leave it to Kim Stanley Robinson, the maverick from Davis, to offer up a science-fiction trilogy about global warming that’s mostly a domestic comedy. Robinson is no stranger to dystopia; he once told me that “We’re living in a bad science fiction novel”—words to hold close in these long cold nights. The books make great company as well, as they offer up a smart recombination of humorous insights into the dynamics of marriage, government, society and the environment of the whole damn planet.

The through line in these novels is Charlie Quibler, a midlevel scientist trying to convince politicians that yes, the sky is blue, and yes, the world is getting warmer faster because humanity has pioneered a means of pumping bucket-loads of greenhouse gasses in the atmosphere, and yes, we’d be well-advised to do something about it before we’re, well, extinct. Robinson crafts great characters, including a President beleaguered by opposition to anything that does not maximize donor corporate profit. Will he succeed? Just look around. Or better still, read Robinson’s engaging narratives and immerse yourself in a world where science matters and some facts prove to matter as well.

Rating: Nine Skateboards. A three-wave ride through the rip curls of family, science and politics. Phew!

Listen to conversations with Kim Stanley Robinson about these books here, here, here and here.

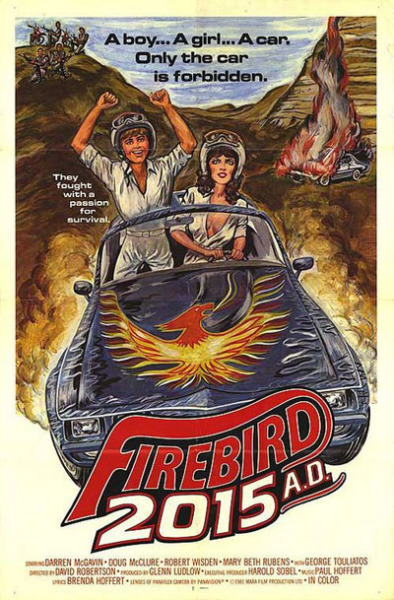

Firebird 2015 A.D.

Screenplay by Barry Pearson, Maurice Hurley and Biff McGuire; Directed by David M. Robertson

This is not a great work of art. It’s not a great movie, and not even a good Douglas McClure movie when compared with his classics like At the Earth’s Core. But it does name-check this year, and more importantly, shows the import of limitations when trying to peer into the future. Having no budget, no new ideas, and probably working from one of those plan-to-lose-money schemes, our three intrepid screenwriters still somehow manage to put their finger into an ugly bit of the American psyche. (Today, to a certain crowd, this might seem like reality TV.)

At a time when Mitch McConnell was the top dog in Jefferson County, John Boehner was cost-cutting his way through his time as the man in charge of Nucite Sales, and the Tea Party was just a gleam in the Koch Brothers’ eyes, Barry, Maurice and Biff took America’s temperature and came up with “burners.” Not burners as in Burning Man, but rather those still willing to drive their sports cars when the President of the U. S. of A. declares gas-burning automobiles illegal—giving birth to Firebird 2015 A.D.. The writers were canny to push forward culture instead of technology. They may have ignored technology because their movie had no budget, but that limitation forced to them to work with what they had. Theirs was the American Ugly right after the Gas Crises of the 1970’s: rev it, crack a six-pack, and try to stay awake through endless desert car chases. Firebird 2015 A.D. is not unlike the traffic you’ll be fighting. And to be honest, 1981 looks a lot like 2015… without the distracted driving, that is.

Rating: Three skateboards, never got off the ground, but thanks for trying. Might have been two skateboards, but with they get one for having Biff on board.

Stranger in a Strange Land

By Robert A. Heinlein (1961)

Robert A. Heinlein is a divisive figure in the world of fiction, and science fiction in particular. And in these divisive times, he still matters. No matter how unpleasant his perspectives may have been, he was always a keen observer of our culture. Moreover, he was quite adept at using science fiction to expose things in a manner that upset a lot of people, entertained a lot of people, and still makes us think to this day. Stranger in a Strange Land was originally conceived as a science fiction spin on The Jungle Book, but Heinlein took it to typically extreme lengths.

Once again, there’s a post-WW III setting, which we’ll conveniently assign the fixed date of 2015. I think Heinlein of 1961 would have grokked that date, and in fact that word (which means “to intuitively and completely understand something”) is now a part of our vocabulary. Heinlein’s Mowgli, Michael Valentine Smith, raised by Martians, returns to Earth with psychic powers that turn him into a religious figure. Heinlein’s vision of politicized religion, power, and pop culture was all right on, even if his predictions about World War were (understandably) wrong. Heinlein’s views are to many sensibilities abhorrent. But—just look around. He had the vibe nailed.

Rating: Seven skateboards. A good flight, but a little too much baggage for most of us.

“Letters of Transit,” Fringe, Season 4, Episode 19

Written by Akiva Goldsman, J. H. Wyman], Jeff Pinkner; Directed by Joe Chappelle (2012)

In the run of this show that was itself very peculiar, generally in the best possible way, “Letters of Transit,” the one episode set in the dystopian future of 2015, was more peculiar than most. Credit that to co-creator J.J. Abrams and executive producer Pinkner, both from the ABC series Lost. Goldsman, who won an Best Adapted Screenplay Oscar for the 2001 (another iconic date!) movie A Beautiful Mind, brings in the heavyweight considerations. While the story arc for this show is not in any way suitable for summary, let us simplify and say that this was the episode in which the Observers, humanity’s distant descendents, having wrecked the earth in the future, pop back to 2015 when things were still good. Then they enslave the humanity of our time—that is, us.

Global warming, global oppression; even just three years ago, it might have seemed a bit outré. But to many, at this point, the Observers might look pretty good. Moreover, the show captures and exaggerates to great effect the feeling that our present feels unpleasantly futuristic. It’s not Alvin Toffler’s famous Future Shock so much as it is future nausea. We feel woozy and confused, and not in a good way. Available via the futuristic platform of “streaming,” the entire run of Fringe is worth binge-watching.

And you thought you had to wait for the future.

Rating: Eight skateboards. A solid ride with lots of TV parking.

A Visit from the Goon Squad

By Jennifer Egan

Future histories that begin in the past are time-tested. Robert A. Heinlein devoted a large portion of his oeuvre to them, and Jennifer Egan’s masterpiece A Visit from the Goon Squad is a superb, moving vision that begins in San Francisco during the punk rock years and ends up in the 2020s. A Visit from the Goon Squad is a literary triumph that is about ten thousand times more entertaining than most fiction tagged with the “L” word. Using intricately interlocked narratives, Egan jumps back and forth in time to craft a vision of the past and the present that is peopled by characters so achingly real that when she heads out into the future, we buy it without question. This is the book that makes Powerpoint poignant.

As with the best science fiction, Egan crafts great characters, and deploys them with insights into our culture and our morals and ethics that are both understated and overwhelming. She fires on all cylinders as her broken musicians, parents, sons, and daughters scatter around the world. She’s smart enough to see the almost universally ignored truth about prognostication: that the future does not replace the present. It is instead heaped on top of it, mixed with it, until one dissolves into another and one day, we’re standing on the Golden Gate Bridge, talking on a cell phone and thinking, “My six year-old self would have loved to know this was in store for me.” As for pros, the SF world ignored this book, while the rest went on to give it the Pulitzer Prize, proving that sometimes, the future does get it right.

Rating: 10 skateboards. Books still matter!

Hear a conversation with Jennifer Egan about A Visit from the Goon Squad here.

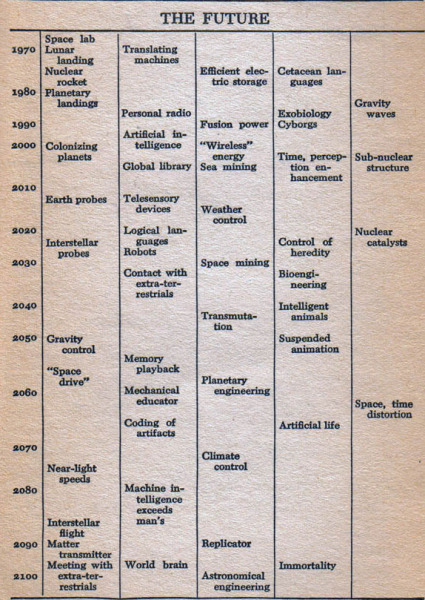

Profiles of the Future

Arthur C. Clarke, 1962

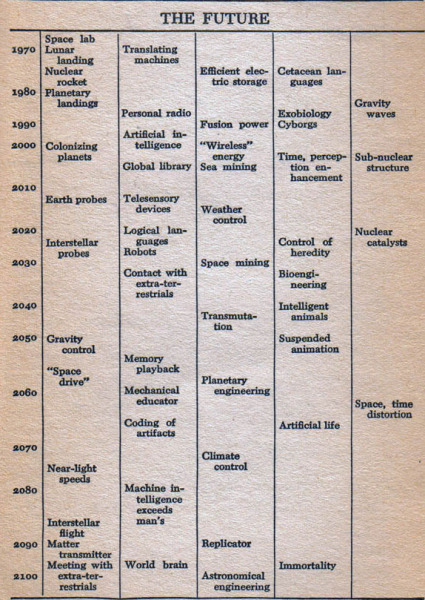

Arthur C. Clarke had a rocking track record when he wrote this book in 1962. He’d predicted (which is to say invented, without profit or copyright) the communications satellite while barely into his 20s, in 1945. By 1960, he was a respected futurist (a real thing by then, which he also helped invent) and science fiction writer. In 1961, he published a work on non-fiction futurology, Profiles of the Future, required reading for a generation of kids growing up on rocket launches and America’s nascent space program. A mere eight years later, he’d collaborate with Stanley Kubrick on 2001, easily one of the greatest science-fiction works ever created.

But Profiles of the Future is not science fiction. One might expect he’d thus get it wrong, but looking at his timeline tells another story. Importantly, this is the first time Clarke stated his Three Laws. They still apply today:

- When a distinguished but elderly scientist states that something is possible, he is almost certainly right. When he states that something is impossible, he is very probably wrong.

- The only way of discovering the limits of the possible is to venture a little way past them into the impossible.

- Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.

Technologically, his timeline is eerily prescient. As a young lad, I remember reading this book with the (Using the Terminology of the Future, Johnny) “takeaway” that we humans had better get around to inventing a decent battery. We’re still at it! Ultimately, Clarke nailed any future in one sentence: “The only thing that we can be sure of the future is that it will be absolutely fantastic.”

Rating: 10 Skateboards and a magic iPhone.

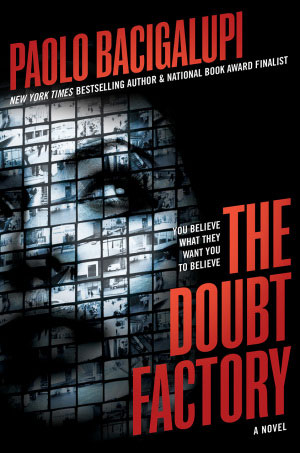

The Doubt Factory

By Paolo Bacigalupi (2014)

While science fiction is supposed to be good at predicting the future, its real strength is to be found, as Cory Doctorow says, in its revelation of the present. Paolo Bacigalupi has written plenty of science fiction set in our future. The Doubt Factory, his current-day YA novel, is not a dystopia (per se), but instead a toe-tapping tale of corporate misdeeds that adults should read both for entertainment value and to get a science-fiction take on the present and recent past that is more mind-boggling than a dozen detonated post-apocalyptic doom zones.

Alix Banks is not a normal teenager, exactly. She’s pretty damn far to the right-hand side of that Luxury Gap. She attends a costly private school and lives in a wealthy neighborhood with her noisy but engaging family. Her father, however, is in the business of casting doubt on science in order to preserve corporate profits. Bacigalupi manages to weave in the sordid story of thousands of child deaths needlessly caused by Reyes syndrome. When it’s done kicking your reading butt, The Doubt Factory will leave you with a prescient vision of the present. It will not make you happy, even if it does entertain.

Rating: Nine skateboards. It’s that good. Do you doubt me?

Hear a conversation with Paolo Bacigalupi here.

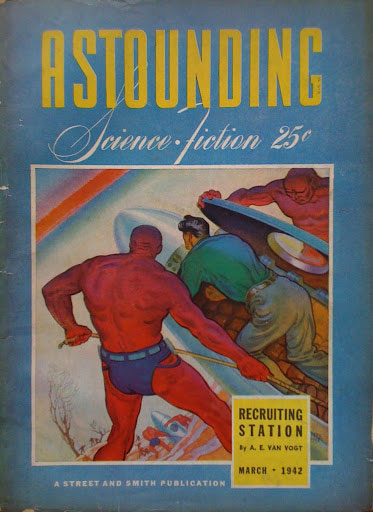

Runaround

By Isaac Asimov (1942)

Here’s the 2015 many were hoping for back in the day before it was clearly not going to happen. America is on the planet Mercury, busily trying to restart a mining operation abandoned ten years earlier.

Let’s put this in perspective. We were walking on the moon in 1972. Is there any reason, other than a preoccupation with, what, a world’s war worth of mini-wars, and consummate greediness, that we could not expect to be mining on Mercury some 43 years later? We pretty much had the technology then. What we lacked was the cultural fiber to do so, which is why cultural science fiction tends to get it right.

But Asimov, writing in the midst of World War II, was serenely and technologically optimistic. Runaround finds Powell, Donovan and Robot SPD-13 (“Speedy”) realizing the “photo-cell banks” are about to die. Speedy is sent to fix them, but instead ends up circling them. The reason for this is another set of three famous laws from science fiction, introduced here for the first time, Asimov’s Laws of Robotics:

But Asimov, writing in the midst of World War II, was serenely and technologically optimistic. Runaround finds Powell, Donovan and Robot SPD-13 (“Speedy”) realizing the “photo-cell banks” are about to die. Speedy is sent to fix them, but instead ends up circling them. The reason for this is another set of three famous laws from science fiction, introduced here for the first time, Asimov’s Laws of Robotics:

- A robot may not injure a human being or, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm.

- A robot must obey the orders given to it by human beings, except where such orders would conflict with the First Law.

- A robot must protect its own existence as long as such protection does not conflict with the First or Second Law.

While Asimov essentially got everything else wrong, he got these so right we still have them with us today. Now that is prognostication beyond the call of duty, when you split the difference between predicting and inventing the future.

Rating: 10 skateboards that may not injure a human being or, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm.

That said, some people get it right, and others manage to be at least entertaining. The tease factor of these visions can be irresistible. Forget your flying cars and jetpacks—who couldn’t want a flying skateboard from 1989’s Back to the Future, Part II? It’s the best pedestal that freedom could hope to have.

That said, some people get it right, and others manage to be at least entertaining. The tease factor of these visions can be irresistible. Forget your flying cars and jetpacks—who couldn’t want a flying skateboard from 1989’s Back to the Future, Part II? It’s the best pedestal that freedom could hope to have.