Well, let’s not go crazy. Still, Noonan’s one man tour-de-force of moviemaking is just waiting to be rediscovered (or discovered), and I would maintain is one of the most overlooked films in contemporary American cinema. Many will recognize Noonan, a top-notch character actor, as “Oh yeah, that guy,” from TV and films. Aside from writing, directing and starring in the film, Noonan composed the somber and affecting music score and designed the sound. Before all that he staged the script as a play, strictly for the purpose of bringing it to the screen. And the budget consisted primarily of the salary from his role as the villain in the Arnold Schwarzenegger vehicle The Last Action Hero.

Why This Film Is So Good

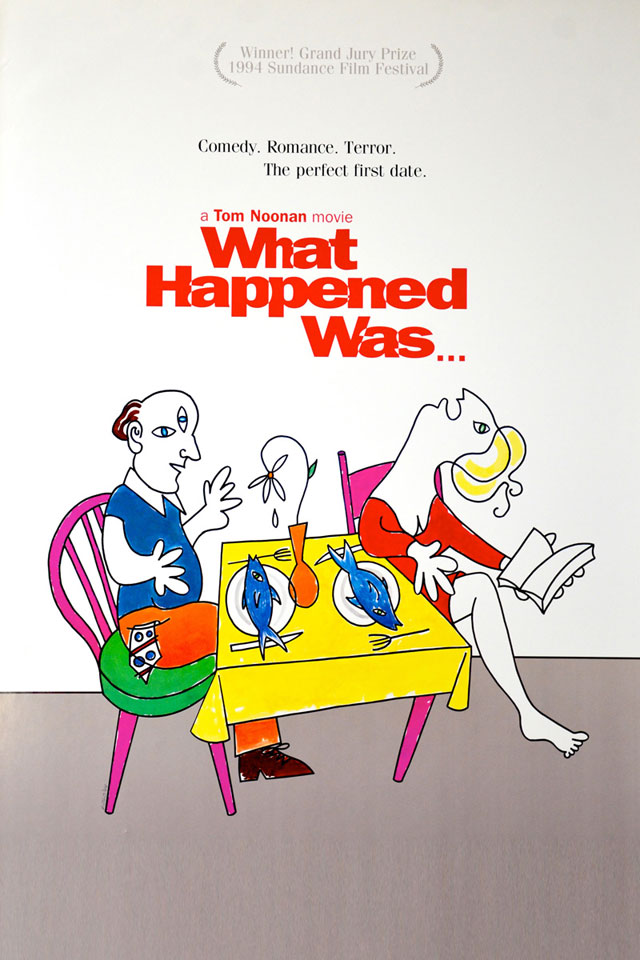

The film has only two characters and takes place over the course of a single first date, all within the New York City apartment of Jackie (Karen Sillas), a 30-something administrative assistant at a law firm. Her partner in awkwardness is Michael (played by Noonan), an older, morose paralegal she works with. This scenario gives off the whiff of studio rom-com, and the original poster for the film might suggest a conventionally kooky, opposites-attract time. He is the embittered longtime underachieving low-level employee, a detached critic who believes he has accrued enough seniority and professional skill to call a spade a spade with impunity; she is the literal-minded former party girl with minimal education, firmly entrenched near the bottom of the office pecking order. She has vicariously thrilled to his refusal to play office politics.

But what gives the film its edge, besides the spellbinding performances, is the destructive way these two recognizable types from any pool of office workers try to navigate the commonplace occurrence of an embarrassing first date. Alternately hilarious and horrifying, their clumsy attempts at normative behavior and conversation slowly reveal the kind of trauma many people carry to work every day along with their microwavable lunches.

One may think a two-hander set in an apartment is inviting staginess and claustrophobia, no matter how satisfying the other elements. But you needn’t go any further than the opening elegiac sequence to see how Noonan’s effective use of limited space conjures up an atmosphere seeping with latent despair.

The film begins with an overhead shot of a woman in bed, half-naked, arms and legs splayed. Dead? No, she gropes for the alarm, as a miniature train encircles a clock, its path suggestive of unproductive effort. She leaves for work, but the camera remains home-bound, tracking the length of the apartment, the light from the windows cold and blue. For some reason, the woman has left the radio on. The camera comes to rest at a corner window, tilting up to a view of the building across the street, an unchanging monolith looming over our vantage point. The light changes in a series of time-lapse shots — from day to twilight to night. Who is the main character here, the woman or the apartment? The spaces we inhabit, we’re quite somberly reminded, continue to exist, whether we’re present or not. Finally, the camera pans down to the woman, home from work. She opens her front door, which we see as a reflection in a window. The hall light flickers. Flash pan, and we’re back inside the apartment. She shuts off the radio.

That is a mini-mood piece in itself, setting both tone and themes for a film that depicts characters who have never really inhabited their own lives.

“It’s hard for me to believe … that we’re not all just extras,” says Jackie later. ”We’re not really here.”

Rather than “open up” the action with gratuitous exteriors, Noonan continues to plumb the limited interior space throughout the film, finding new vistas in the contours of the apartment by perceiving it through the characters’ cracked personalities. Frequently he calculates his shots to reflect a psychological state of anxiety or barely suppressed hysteria. Typical is the blocking after Jackie has buzzed Michael in downstairs. As the camera dollys in to the front door, she flits in and out of frame on either side, like some demented pixie, straightening the house in a near panic. Later, when she reads to Michael from a children’s book she has written (starting with a blowjob and decapitation, and getting weirder from there), we see Michael’s growing agitation from a shot inside a dollhouse, as if it has been populated by the very characters from her horrific tale.

Noonan told me there’s more going on visually beneath the surface. He overexposed and under-printed the film (called pull processing) before Jackie reads her story, creating a muted look; and did the reverse — push processing — afterward, rendering the images grainier and the colors more vivid, to “make the story more raw,” he says. In addition, the color scheme was changed, down to switching a lone green fish in a tank to one that is red.

Noonan also toyed with the sound design. He had children scream lines from Jackie’s crazy story from the street below before we actually see that scene. “You’re hearing these voices say things that are subliminally going into your mind,” Noonan says, “and then later when she says them, you’ve already heard it.” He also took the disconcerting screech Jackie makes to emulate a car pulling out and put it under the sounds of her chair moving.

The reason?

“Repeating images and sounds can be pretty powerful in a movie – especially if (it’s) done without tipping your hand to the audience. If the audience hears something that they subliminally recognize, it has a good chance of bringing them into the story. Making what they are seeing new but (it) feels familiar. Did you know that when you are under great stress your brain releases a chemical associated with memory function and gives you the feeling that you’ve seen what you’re seeing before?”

Because he had done so much advance preparation with his director of photography, Joe De Salvo, it took Noonan and crew just 10 days to shoot.

“We shot listed and shot listed. We worked on how to shoot it for months. By the time we finally shot, we had worked out pretty much everything.”

That intense preparation included cementing the script. Reviewers have speculated some of the film may be improvised, a natural supposition since the dialogue, which contains virtually nothing extraneous to the story, feels meandering.

“People think that (it was improvised) because it had such a naturalistic feeling,” Noonan says.”But a lot of those little flubs were things that were written in.”

As Jackie and Michael’s encounter progresses, harmless eccentricity gives way to hints of deep psychological dislocation. The possibility of both sex and violence infects their interaction, and it all leads up to a reveal that is both ordinary and all the more devastating for it.

I put What Happened Was… in the same category as films like Safe and 3 Women — works that convey horror without resorting to the supernatural, because what is truly frightening is that which is all around us but must be intentionally overlooked. Why? To get along, to fit in, or merely to keep a nervous breakdown at bay.

Developing an Audience

I looked for What Happened Was…, which Noonan says cost just $137,000, on some Best of the 1990s lists, but all I could find was a mention in Slant Magazine, where it came in at No. 157.

Despite the accolades at Sundance, the film flopped upon release, both Noonan and producer Scott Macaulay say, partly because the Samuel Goldwyn Company put very little into its promotion.

“They decided to put all their money into (David Mamet’s) Oleanna and very little into What Happened Was…” Noonan says. After its opening at the Angelika in New York, “it went on a calendar house circuit around the country to little theaters. I think we only had two prints.”

Still, considering its unusual nature, you’d think the film would have developed some sort of following over the years. One big impediment to that: It’s never been released on DVD.

“I think that’s probably the big reason why it’s been underexposed for the current generation of viewers,” says Macaulay.

While cautioning that independent film is still a risky proposition, Macaulay says it might be easier to build an audience for What Happened Was… today. “We’re talking about a different era,” he says. “There are a lot of tools for filmmakers to get their work out today and promote their films, whether they’re getting distributed by larger companies or not. Those tools didn’t exist in 1994. A filmmaker’s presence can be amplified by social media, there are lower cost ways to market a film. A cult audience can be aggregated in a way that was more difficult back then.”

I asked Ted Hope if he thought the film might thrive more in today’s media ecosystem.

“What Happened Was … garnered great and deep love from some passionate advocates during it’s brief run,” he answered in an email. “Could we have amplified that with today’s tools? Definitely. (But) the challenge of having it catch on today would be complicated further by the onslaught of everything else. Back in its day, it was rare to make something for $100K; today it is commonplace.

“There is no denying the film’s distinction though, and that will always be the first step towards aggregating anyone around anything.”

Noonan did not recoup his financial investment in the film. “I sold it for about 100-and-something, and it all went for deferrals for the crew, and I didn’t get anything,” he says. “It played in the theater and didn’t make any money. On Netflix it made very little.”

He went on to make just three other movies, including The Wife, which received better reviews from Ebert and the Times, and Wang Dang, which Noonan says was ruined by his shooting it himself. His most recent is The Shape of Something Squashed, from a play he wrote and directed for his New York City theater, The Paradise Factory. He has submitted that to Sundance and is waiting to hear back.

“It’s disappointing to me I haven’t done more,” he says. “I did What Happened Was… and The Wife, and I thought I’ll be doing this for the next 30 years, I’ll be like Woody allen, I’ll make 50 movies. But it’s been very disappointing.”

Still, What Happened Was… is almost a career in itself.

You can rent or buy What Happened Was…. on Amazon or purchase it on iTunes.