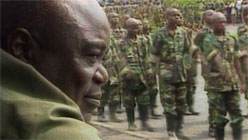

The history of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, as it is now called, is no less complicated and messy than that of any other country. But most Westerners have distilled that history into two periods and two individuals: The cruelly exploitative colonialism practiced by King Leopold II of Belgium and, beginning half a century later in 1965, the corrupt 31-year-reign of army officer-turned-dictator Joseph-Désiré Mobutu.

There’s a bit more to the story, of course. The Belgian documentary Kongo: 50 Years of Independence of Congo, screening Wednesday, February 15 at the Pacific Film Archive in Berkeley as part of the annual touring African Film Festival, represents an unexpectedly restrained and occasionally inspired attempt to pierce two countries’ heart of darkness. Comprised of three artfully constructed, 52-minute chapters, the 2010 television production is unexpectedly imbued with a sense of injustice rather than horror, and of blown opportunities instead of pervasive, persistent tragedy. That approach may be responsible, but it doesn’t exactly quicken the viewer’s pulse or dispense catharsis.

The first two episodes, The Unbridled Race (directed by Samuel Tilman) and The Great Illusion (Daniel Cattier), evince a tone of dispassion tinged with compassion, irony and polite disgust. Only the audacious “The Failed Giant” (Jean-François Bastin and Isabelle Christiaens), which takes us from 1960 to the present and is narrated by the late Prime Minister Patrice Lumumba — pointedly commenting on the various events and developments that have occurred since his murder in January, 1961 — butts heads with history in a way that shakes us into seeing and thinking beyond two-minute nightly news segments.

A few facts: More than 10 million people were taken out of the Congo over a span of three centuries by the Portuguese and sold as slaves (mostly to Brazil). The Congo is 80 times as large as Belgium, which originally insinuated itself on the scene as a benign presence ostensibly with humanitarian aims.