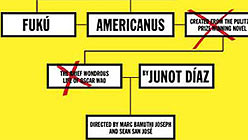

Yes, novel adaptations are cursed, and Fukú Americanus is no exception. Adapted by Sean San Jose from Junot Diaz’s Pulitzer-winning novel The Brief, Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao, and staged by Campo Santo at Intersection for the Arts, the play is a mess — a lovely, frustrating mess, that translated the excitement of the book, but fumbled the storytelling.

Oscar Wao thrilled American readers when it appeared in 2007 on the heels of a century of endless repetitions of the same immigrant narrative. The book was recognizably an immigrant story, yet it turned the tropes on their ears. Far from pandering to a non-Spanish-speaking readership expecting its exotica to be translated, Oscar Wao spoke the college-educated, ghetto-inflected Spang-nerd-glish its macho, comic-book-reading Dominican narrator spoke. Its metaphors came from Tolkien and The Silver Surfer. Its plot didn’t follow the arc-de-triomphe of the traditional immigrant tale, but rather the melodramatic twists of a generation-spanning curse.

Oscar Wao knew what it was about, what story it was trying to tell, and how it was trying to tell it; Fukú Americanus can make no such claims. What is, in the novel, a tour-de-force braiding together of 20th century Dominican history, Caribbean/US immigration issues, three-generations of familial tragicomedy, and revenge-of-the-nerd story, becomes, in the play, messy, incongruous, and incomplete … but also funny, exciting, culturally canny, and completely in love with its characters. The play extinguishes the brilliance of the novel — its powerful balancing act — but manifests, even heightens, the novel’s human appeal, its abundant energy and humor, its hybrid language, and its loveable characters.

Co-directors Sean San Jose and Marc Bamuthi Joseph embody the book with an ambitious physicality: a combination of comic book tableaux, telenovela melodramatics, and chaotic modern dance. A wall painted in a grid of red and blue squares creates comic book panels against which the actors freeze in place to deliver monologues and adversarial dialogues. Several platforms move easily, stack up, or bridge one another to force and facilitate the actors in motion; when not trapped in the panel of a comic or the frame of a television set, the characters spin in a whirlwind of motion and rapid-fire happenstance. Simple costumes in black and primary or neon colors do triple duty as superhero disguises, character gestures, and period costume.

The staging doesn’t always land squarely. There are times, especially during the first twenty minutes or so, when the piece isn’t so much a depiction of chaos as it is chaotic itself; times when the melodrama isn’t so much a knowing commentary as it is … just loud. But these are the consequences when you take big, ambitious risks, and the mere presence of artistic ambition onstage is gratifying. It is all the more so since the risk mostly pays off. Giving talented performers layered, complex, and meaty roles is a good strategy; without exception, the performers meet every shift in tactic and texture with energy and power.