Imagine going through the seven stages of grief in seven days. That monumentally disorienting premise is the framework for Venita Blackburn’s debut novel, Dead in Long Beach, California. The novel centers on Coral Brown, a Black lesbian sci-fi writer, who walks into her brother Jay’s apartment in Long Beach and discovers he has died by suicide. The whole story takes place within the week she finds his body, one Friday to the next. Amidst chapters titled after days of the week, memory, grief, denial and time bleed into each other.

Blackburn is an associate professor of creative writing at California State University, Fresno, and the founder and president of Live, Write, a nonprofit that offers free creative writing workshops to communities of color. She has previously published two short story collections. The most recent, How to Wrestle a Girl, was a 2022 finalist for the Lambda Literary Award for Lesbian Fiction. Reviewers praised the collection for its playfully inventive structure; in it Blackburn alternates between first and third person, uses her background as a flash fiction writer to pack big feelings and stories into small words counts, and blunts tragedy with farce. Echoes of these writing flourishes can be found in her latest offering.

“Californians walked like they were underwater,” Blackburn writes in Dead in Long Beach, “slow, with all the time in the universe.” This warped temporal reality is compounded in Compton, where she notes “even time moved like water … a thing to drown in, a thing necessary for life.”

Like Blackburn, whose hometown is Compton, Coral is a South Los Angeles native. In suffusing the book with Coral’s memories — tender, bitter, formative — Blackburn effectively turns it into a love letter to the region. In the ’90s when Coral was young, the city was “a mecca, an Eden, a place to dream, honor; to buy liquor, doughnuts, fried chicken and greens; a place to loathe and protect.” Coral came of age in this place. She was familiar with its music and violence — a regularity she regarded as “white noise.” Still, death is not something you can prepare for.

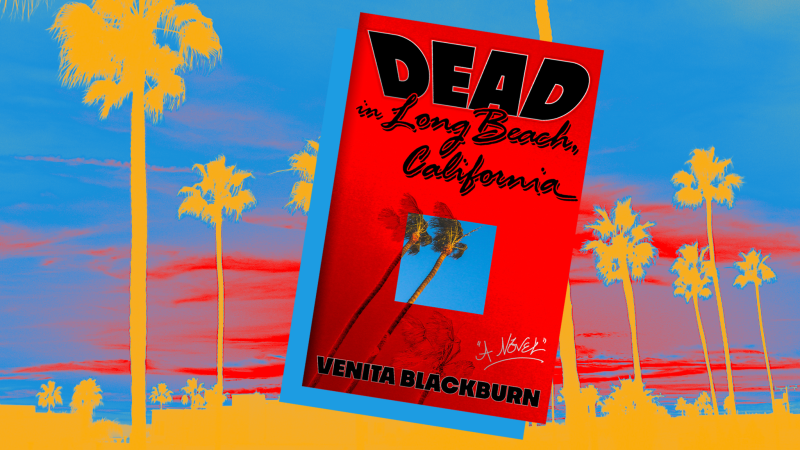

“Death IRL is an ice bath from the inside out,” the narrator reflects. Blackburn’s writing is similarly bracing. The book’s format is experimental and hard to pin down — the label “a novel” is in winking quotes on its cover. We meet the narrator in the opening sentence as a mysterious and nameless ‘we’ announces, “We are responsible for telling this story, mostly because Coral cannot.”