View the full episode transcript.

In Indigenous protocol, we’re beginning this week’s episode honoring the original stewards of this land that many of us in Frisco now occupy — the ancestral homeland of the Ramaytush Ohlone.

Now, let’s take a trip down Valencia Street to La Misión.

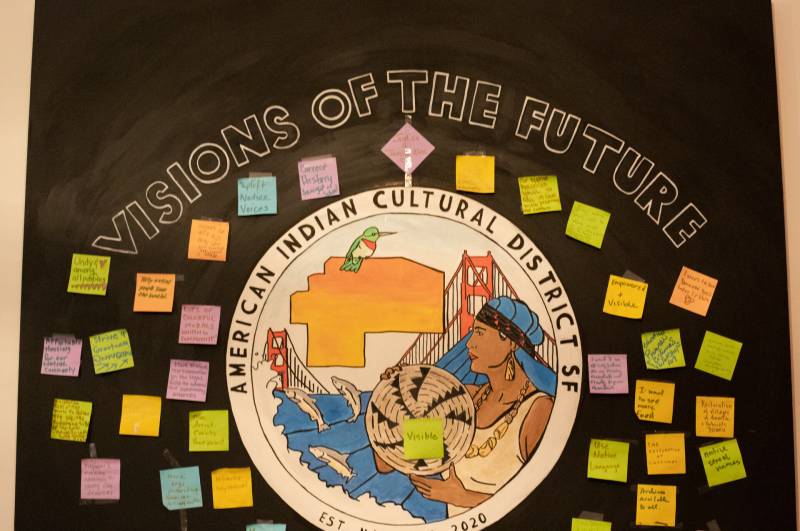

The neighborhood is home to not one, but two rich cultural districts. Calle 24 Latino Cultural District was first established in 1999. More recently, in 2020, it was joined by the American Indian Cultural District — a home base for the Urban Native community. Its aim is to uplift the culture, history, and continuing contributions of American Indians in San Francisco and beyond.

On this week’s Rightnowish, we introduce you to some of the people behind this cultural district that’s the first of its kind in the Golden State.

Mary Travis-Allen (Mayagna, Chortega, Seneca) is the President of the District’s Advisory Board and recalls memories of “Little Rez” along 16th Street. Debbie Santiago (Washoe, Osage) and her mother, Alberta Snyder (Washoe) share their memories about the SFUSD’s Indian Education Program that ran out of the American Indian Cultural Center on Valencia Street in the 70s and 80s. Karen Waukazoo (Lakota) remembers her late mother and local hero, Helen Waukazoo, who co-founded Friendship House, the oldest social service organization in the United States run by and for American Indians. Last but not least, we venture to the waterfront at Fort Mason to talk with Sharaya Souza (Taos Pueblo, Ute, Kiowa), the Executive Director of the American Indian Cultural District about the legacy of the Alcatraz occupation.

There are so many Native stories alive in La Misión — we hope this is just the start to more of us hearing about them.

This story was originally published July 22, 2022.

Below are photos along with some lightly edited excerpts from the episode.

Mary Travis-Allen: Warren’s Slaughterhouse Bar … was a meeting location for us back in the 60s and 70s, and helped foundationally bring our community together.

With people coming from all over the states and different reservations, they were able to socialize — but more importantly, discuss the similarities of the struggles that they were having… because what people were experiencing here was a failure of yet another promise by the government to move our communities into the city and assimilate into America. They struggled for employment, and they found that there really wasn’t the resource or the realization of this American Dream that had been promised to them.

Debbie Santiago: Our people … after a long period of time, have been overlooked and unseen. People come up to me and say, “Oh, you don’t exist.”

Alberta Snyder: “I didn’t know there was any American Indian people still living here in the Bay Area …”

And so we have to laugh and tell them, “I’m American Indian, number one, and I’ve lived here in the Bay Area all my life.” … There’s a big community of American Indian people from different tribes that was relocated into the Bay Area. So to me, it’s always funny that they’re thinking, you know, that we’re gone, with the cowboys or whatever.

Karen Waukazoo: My mom came out around early 60s … She was taken from her family by the U.S. government to go to a boarding school. … While she was here [in San Francisco] she saw that there was so much alcoholism, and there was no place for Native Americans to go for that. That is when she started this program.

Marisol Medina-Cadena: And the alcoholism that your mom was seeing didn’t happen out of nowhere, right?

Karen Waukazoo: Yes, completely! So, Natives face all the same issues as when my mom first came here: housing, jobs, health, mental health care, suicide prevention, substance abuse treatment… My mom would always say it’s a shame that Natives are homeless on their own land.

Karen Waukazoo: The unique thing about Friendship House is that it provides these services in a very culturally specific way, which is important to our Native people. There can be a deep-seated level of distrust in government services because … being separated from your family can cause hurt and pain…

Sharaya Souza: What people don’t know is that at one point, the Mission district was called the “Red Ghetto.” At one point, it was a thriving, bustling area of American Indian businesses, organizations and community members. And today, when we look at the data that comes from a map, we still see many of our members actually reside in the cultural district. …It is a continuing history. It is a living history.

One of the biggest things that I’ve noticed coming into San Francisco — aside from the fact that we don’t have tribal liaisons like we do in the governor’s office or at state institutions — is that this city is predicated on equity and racial equity … yet [American Indians] have the lowest graduation rates, the highest suicide rates, the lowest employment rates, the second lowest income, the lowest homeownership rates. Our funding for our youth is completely disproportionate. And it’s not about competing with each other for resources. It’s really just understanding how we’ve constantly turned a blind eye to American Indians.

Episode Transcript

[Music]

Marisol Medina-Cadena, co-host: What up y’all?! I don’t know about you but November flew by. Scratch that, it zoomed by. Scorpio season did a number on me, and from my point of view, it also did one on our global community. This month also happens to be Native American Heritage Month.

Maybe last week, you had a feast with your fam, or a lovely Friendsgiving. For many Native families, the American holiday is considered “A Day of Mourning.” Because for them, it symbolizes the betrayal and bloodshed by the “pilgrims”… or “settlers” if we wanna be historically accurate.

I know, I dropped a lot on you. So, let’s take a deep breath and exhale together.

[breath]

For this week’s episode, the Rightnowish team decided to throw it back to an episode we made last year: where we took you to meet culture-keepers in Frisco’s Mission district, who are fighting Indigenous erasure.

And since we reported this story, there’s been some cool developments. Visual markers like, colorful murals, sleek pole banners and official street signs have been installed… The goal: to remind us that we’re still on “Native Land.”

Okay, here we go…

[Music]

[street noise, quiet traffic, and sounds of chatter]

Sharaya Souza, guest: So as American Indian people, it’s always protocol to acknowledge whose land you’re on. And today, no matter where you go in the city and county of San Francisco, you’re on Ramaytush Ohlone land.

Pendarvis Harshaw, co-host: Hello, wassup world it’s Pendarvis Harshaw, host of Rightnowish…

Marisol Medina-Cadena: And I’m Marisol Medina-Cadena, the Rightnowish Producer. And we’re coming to you from KQED’s studios on unceded Ramaytush Ohlone land… originally known as Yelamu.

[Music]

Pendarvis Harshaw: Yeah and that voice you heard earlier is that of Sharaya Souza.

Sharaya Souza: Hello everyone, my name is Sharaya Souza, Taos Pueblo, Ute, and Kiowa, and I’m the executive director and co-founder of the American Indian Cultural District.

Pendarvis Harshaw: Two years ago, San Francisco became the home of the first American Indian Cultural District of its kind in California. What makes it so special… is that it is a hub honoring the multiplicity of urban Native groups that reside in the Bay, in addition to the Ramaytush [ram-uh-tush] Ohlone. It’s located in the Mission District…

Sharaya Souza: What people don’t know is that at one point, the Mission district was called the “Red Ghetto.”At one point, it was a thriving, bustling area of American Indian businesses, organizations and community members. And today, when we look at the data that comes from a map, we still see many of our members actually reside in the cultural district // and that it is a continuing history. It is a living history.

Marisol Medina-Cadena: We’ve talked about the “Urban relocation program” on Rightnowish before but, for those unfamiliar… It was a federal policy passed in 1952 that tried to assimilate American Indians living on the Rez or Pueblos by incentivising them to move to urban cities like L.A., Detroit, Chicago, Oakland and San Francisco.

Pendarvis Harshaw: And with all these Native folks arriving in the Bay during a time of red lining, racial discrimination, and low wage jobs for people of color… American Indians felt enough was enough, and a movement started to grow. In 1969, a group of activists organized a historic takeover of one of the City’s abandoned islands that would be known as the Alcatraz Occupation.

Marisol Medina-Cadena:Over 100 American Indians occupied the defunct prison and surrounding island to establish a sovereign Native space. It was an effort to push the Federal government to honor a 1868 treaty with the Sioux Nation… that promised to return out-of-use land to Native groups. Here’s Richard Oakes, one of the lead organizers, speaking to news cameras:

Archival Clip: “We wish to be fair and honorable in our dealings with the Caucasian inhabitants of this land and hereby offer the follow treaty: we purchase said alcatraz island for $24, glass beads, and red cloth, a precedent by white mans’ purchase of a similar island 300 years ago”

[Music]

Pendarvis Harshaw: But even before the Alcatraz occupation, American Indians were organizing in San Francisco. The Mission District was a hub for political organizing, cultural activity, and social services by and for Native folks.

Marisol Medina-Cadena: Which is where today’s cultural district comes in… because it’s about preserving that activist and cultural history that began in the ‘50s… continuing through today, and is foundational to this city’s DNA.

Pendarvis Harshaw: To dig deeper into urban Native history in the Bay, Marisol’s going to take us to a few of the sites that are culturally significant within the district. But, first let’s situate you on the map. It’s more than just the area surrounding Mission Dolores Church, right?

Marisol Medina-Cadena: Right! Get yourself to Dolores Park. Walk down 16th to Mission street. And cool fact: the park was known as “Chutchui” by the Ramatush Ohlone pre-Spanish colonization. It was a central gathering spot back then!

Pendarvis Harshaw: It’s still a central gathering spot, looks totally different now.

Marisol Medina-Cadena:Yeah, and to be honest, it’s been a long time coming for the city of San Francisco to recognize Native contributions… at this scale. So, let’s buckle up. We got learning to do.

[street noise, quiet traffic, and sounds of chatter]

Marisol Medina-Cadena: Let’s begin our tour near 16th & Mission street, just a block up from the BART station. We’re in front of a gray painted stucco building. It’s a pretty plain looking bar right next to a popular Indian & Pakistani restaurant.

Mary-Traves Allan, guest: Hi, my name’s Mary Travis Allen. I am Mayagna, Chortega, and Seneca. I am the advisory board president for the American Indian Cultural District. Right now, we’re standing in front of 379 16th Street, which currently is a bar, Bond Bar. But its historical merit to us in our community is that it was the former location of Warren’s Slaughterhouse Bar, and that was a meeting location for us back in the ‘60s and ‘70s and helped foundationally bringing our community together.

With people coming from all over the states and different reservations, they were able to socialize, but more importantly, discuss the similarities of the struggles that they were having because what people were experiencing here was a failure of yet another promise by the government to move our communities into the city and assimilate into America.

They struggled for employment, and they found that there really wasn’t the resource or the realization of this American dream that had been promised to them. Right down the street was the American Indian Center. So, you know, a lot of the resources and conversations that existed there kind of came over to this area.

Those conversations, in addition to identifying, you know, social needs, employment opportunities… there was a hiring hall right down the street at the Redstone building. So there was union organization that was going on there. You know, a lot of it that cascaded over into this location.

Richard Oakes you know, this was one of his 1st employments here.

Marisol Medina-Cadena: This area at the time that you’re talking about was referred to as the “Red Ghetto,” who called it that and why was it called that?

Mary-Traves Allan: In this area, you know, was single occupancy housing, low income housing, the lack of other resources, it was redlined. It was the least desirable place where people would want to live and also the loans weren’t being given.

And so, with our concentration of our people in our community here, we came to be known as the “Red Power” movement here.

And so the term “Red Ghetto,” you know, was applied to this area because it was a ghetto. It was underserved economically, but it was also the hub and existence of our community.

[traffic sounds continue]

[Music]

Mary-Traves Allan: I remember kind of because I was a kid at the time. There were dances, ya know. There were people that were meeting and getting together because this urban environment took away a lot of our cultural norms, you know, from the reservations from our cultures and got blended together here. The other thing it presented and I have to speak to is, is the police. The police amped up its patrols around here. Our people were getting arrested.

Ya know, a report that came out in the ‘70s, the late ‘70s that said that our people were being targeted by stereotyping and profiling, and they were being arrested 4x higher than any other ethnic group in this city, you know.

So in our struggles to exist here in the city, we had locations, you know, like Warren, where we could go and gather and talk about these things, ya know. Instead of it making us weaker, it made us stronger because that collective thinking, that thought, that process and that advocacy… that happened here.

[sounds of chatter and cars passing]

Marisol Medina-Cadena: A few blocks from the bar, I met up with Debbie Santiago and her mother Alberta Snyder at one of the former sites of the American Indian Cultural Centers. They stood shoulder to shoulder, each with walking canes.

Alberta Snyder, guest: I’m Alberta Snyder, Washoe and Rode Washoe member of the California Nevada tribe from Carson, actually the Carson Valley area. And I was born and raised here in San Francisco.

Debbie Santiago, guest: Hi, I’m Debbie Santiago, and I am an enrolled member of the Washoe tribe of Nevada, California, and I’m on my mother’s side and I’m also Osage from my father’s from Oklahoma.

Marisol Medina-Cadena: And can one of you tell us where we’re standing today?

Debbie Santiago: This is the old Indian center that opened in the early 1970s. So all my memories are from the center here… We had a women’s basketball team which was called Eagle Shawl, and we would have tournaments and playing in different areas from California all the way to Nevada. It was pretty awesome to be around my own people when we won.

Here at the bottom… we had social services: job training. And then upstairs we had a little event area with the stage, dance class, drum class, bead making classes, shawl classes. My mother was a big part of that.

Marisol Medina-Cadena: Today, it’s a nondescript office building. A bright mural showing tepees belonging to Plains Indian is no longer. It’s now a canvas for graf writers.

[Music]

Marisol Medina-Cadena: Debbie’s mom Alberta eventually became a teacher at the center. It was a hub of so much cultural and education activity. They reminisced about the days when Valencia street was transformed into pow wow grounds…

[sounds of powwow drums and jingle dancers]

Marisol Medina-Cadena: …which really struck me because nowadays if you want to go to a public powwow you gotta make the trek to an elite college campus like UC Berkeley, Stanford, or Santa Clara.

Debbie Santiago: So many people from all over, big time dancers would come down all over the place and booth vendors. And, but this day, when we had that street fair closed and that was the biggest I’ve ever seen here in Valencia Street in front of the center.

Marisol Medina-Cadena: The American Indian Center is no longer at this building, and the one that came after closed due to lack of funding. So, today they’re a virtual organization. I asked Debbie and Alberta about this.

You don’t have a physical space?

Debbie Santiago: No. We need a center and we need it now.

Alberta Snyder: The reason we want a physical space is because it gives us a chance to gather, for families to see each other because many of us are spread out within the San Francisco community.

And it also gives us, the elders, a chance to get out and be with family. You know, we’ve discovered that there are many elders that are alone. They are in their rooms and you know, they don’t get a chance to be around people.

Some of them don’t eat, but maybe once a day, so we could have them there for lunch and dinner.

Marisol Medina-Cadena: Cultural centers aren’t just active when folks are making art, or there for an event… They can also be gathering places for people to simply be in community with each other – which is vital in a City that can render living American Indians as invisible.

Debbie Santiago: Our people here, is… after a long period of time is been overlooked and unseen. People come up to me and say, Oh, you don’t exist.

Alberta Snyder: I didn’t know there is any American Indian people still living here in the Bay Area and I… And so we have to laugh and tell them I’m American Indian number one and I’ve lived here in the Bay Area all my life. And I said, and there’s a big community of American Indian people from different tribes that was relocated into the Bay Area.

So… to me.. it’s always funny that they’re they’re thinking, you know, that we’re gone in with the cowboys or whatever. [laughs]

Marisol Medina-Cadena: At the end of our conversation, we parted ways. Then, I headed over to a building on Julian Way and 15th street. For the last 50 years it’s been the “Friendship House,” the oldest social service organization in the United States run by and for American Indians… I’m here to meet another community leader…

Karen Wakazoo, guest: Karen Wakazoo, my role at Friendship House is data and contract specialist and I am Lakota. I am from Standing Rock and Rosebud.

Marisol Medina-Cadena: Karen is the daughter of one of Friendship House’s founder, Helen Wakazoo.

Karen Wakazoo: My mom came out around early 60s … She was taken from her family by the U.S. government to go to a boarding school.

But while she was here she saw that there was so much alcoholism and there was no place for Native Americans to go for that…That is when she started this program.

Marisol Medina-Cadena: And the… alcoholism that your mom was seeing didn’t happen out of nowhere, right?

Karen Wakazoo: Yes, completely! So, Natives face all the same issues as when my mom first came here: housing, jobs, health, mental health care, suicide prevention, substance abuse treatment…

My mom would always say it’s a shame that Natives are homeless on their own land.

The unique thing about Friendship House is that it provides these services in a very culturally specific way, which is important to our Native people.

There can be a deep seated level of distrust in government services because of that being separated from your family, can cause hurt and pain and that…

[Music]

Marisol Medina-Cadena: Karen tells me, there’s a plan to rename the street where Friendship House is located… from Julian Ave to Wakazoo Way in honor of her mother, who passed away in 2021.

Karen Wakazoo: Ya know I was thinking about her the other day, how her office would.. was right there and she would come down and it was like she was a celebrity. You know, people wanted to hug her and be around her… she just made you feel special. But her vision to continue going into the future was “The Village”

[Music]

Marisol Medina-Cadena: The street renaming — will accompany a new 6 story building named “The Village” that would offer even more health services, temporary supportive housing, job training, and a rooftop farm for cultivating plant and food medicine.

When your mom was running this space, uh… did she have to pressure the city government to recognize the work people were doing here and to, like, fund it or?

Karen Wakazoo: There were times that she just got her coat on and went down to City Hall and knocked on the door until somebody let her in. She wasn’t scared of going and getting what she needed done.

Marisol Medina-Cadena: Is there a similar kind of battle today to get the city to fund the resources you all provide?

Karen Wakazoo: We always kind of have to show that we’re still here. You know, we always kind of have to show that, you know, we’re not gone. We are the only group that has to prove our blood quantum. You know, who else does to do that? Horses and dogs? Yeah, it’s crazy, huh?

Marisol Medina-Cadena: Yeah…

[Music]

Marisol Medina-Cadena: When Julian Avenue gets renamed after your mother, more people will know her name…

Karen Wakazoo: That is the one thing, you know, I want to get The Village built and we’re going to have a statue of her, and I just look forward to that day.

She never quit. She worked from a secretary all the way up to a CEO. It was difficult, but she made it and she didn’t quit. And that’s something I’m trying to follow in her footsteps with.

[sounds of waves on a beach, seagulls calling]

Sharaya Souza, guest: Everywhere you walk in San Francisco, you’re on Native land. But I think in the modern terms, in the legislative terms of having a cultural district is really visibility.

[Music]

Marisol Medina-Cadena: Last but not least, our tour ends with, who we met at the start of this episode. She’s Executive Director and Co-Founder of the American Indian Cultural District.

Sharaya Souza: I feel like it’s always been a dream. The more I hear from our elders of something that they wanted here, you know, when we think about the occupation of Alcatraz was a call for a space. And so we didn’t just get a space. You know, we got an entire legislated space on a map.

San Francisco to me, I’ve only been here 3 years, I’m from Sacramento. I always thought of San Francisco as the home of the, you know, Alcatraz occupation. Oh my gosh, they must be like, that’s where the American Indian Film Festival happens. They’re so liberal they must really care about American Indians. And when I got here, it was really disappointing to learn that we don’t have any American Indians on the Board of Supervisors. We don’t have any American Indians in the human rights commissions. We don’t have any American Indians in really high positions within our city government.

One of the biggest things that I’ve noticed coming into San Francisco, aside from the fact that we don’t have tribal liaisons like we do in the governor’s office or at state institutions, is that this city is predicated on equity and racial equity, and that’s our big push in the city. Yet we have the lowest graduation rates, the highest suicide rates, the lowest employment rates, the second lowest income, the lowest homeownership rates. Our funding for our youth is completely disproportionate.

And it’s not about competing with each other for resources. It’s really just understanding how we’ve constantly turned a blind eye to American Indians.

Just recently, we were able to work with the mayor’s office to really edit the stats that were not 0.3% of the population or 1.1 % of the population. And after again, the 2020 redistricting stats, we actually came out as 2.1 % of the population, with over 17,956 American Indians that identified as American Indian plus another race and 6,475 that identified as Single Race American Indians. So we are here. We’ve been here.

[Music]

Marisol Medina-Cadena: The American Indian Cultural DIstrict has their office here in Fort Mason, not the Mission district because this area is also significant to urban native folks. In case you didn’t know, the annual 2spirit powwow is held here. Put on by Bay Area American Indian Two-Spirits. And the Alcatraz occupation happened just a stone’s throw away from here.

Sharaya Souza: Every day that I see Alcatraz outside, it inspires me because the people that came here to Alcatraz came to bring visibility to relocation, termination – the federal government policies in the 1950s, which meant to terminate American Indians and urbanized them and move them into cities in order to assimilate them. But what it ended up doing is it ended up making stronger. Instead, we built inter-tribal communities here, and what Alcatraz did was it was really a catalyst.

It was sort of the first cultural district before cultural districts were born because folks basically looked at the different treaty rights and they said based off of the fact that this is, you know, federal land and it is unoccupied, you know, given them the rules that go along with the federal government, this could potentially be Indian land. And so they occupied it.

So for me, it’s it’s a reminder of the work that was done before me. It’s the reminder that that work needs to keep continuing. And it’s a reminder that Alcatraz is a living movement and it’s still an inspiration to many people today and that those people who occupied are still here.

That is why I think the district is so symbolic… is because you can’t deny that we’re here anymore. You can’t say that we don’t exist.

[Music]

Marisol Medina-Cadena: Thank you to the American Indian Cultural District team who worked with me to make this story happen. That’s Paloma Flores and Tal Quetone. Also, special thanks to Janeen Antoine for connecting us.

For more info on the cultural district look them up https://americanindianculturaldistrict.org/. And if you want to know more about Oakland during urban relocation, you can go listen to our episode with comedian Jackie Kelliaa. Thanks!

Pendarvis Harshaw: The producer and host of this episode is Marisol Medina-Cadena.

This episode was edited by Jessica Placzek, Kyana Moghadam and Jen Chien. Our engineer is Ceil Muller. Corey Antonio Rose is our production intern. Our engagement team is made up of Justin Ebramhemi, and Ria Garewal. Kyana Moghadam is the senior producer of podcasts. KQED execs are David Markus, Holly Kernan and Jen Chien.

I’m Pendarvis Harshaw and I will be back in the host seat next week… In the meantime go to the Mission and visit the cultural district for yourself.

Peace.

Rightnowish is a KQED production.

Rightnowish is an arts and culture podcast produced at KQED. Listen to it wherever you get your podcasts or click the play button at the top of this page and subscribe to the show on NPR One, Spotify, Apple Podcasts, TuneIn, Stitcher or wherever you get your podcasts.