As a kid growing up in Alameda, Joey Enos was obsessed with all things Disney. “I wrote letters to Michael Eisner as a kid, begging him for a job,” he says, slightly embarrassed, standing in his Oakland studio just off of Telegraph Avenue.

Sometimes, the budding artist sent more than letters: “I drew a picture of me at a drafting table, then I cut out a picture of Disney’s head, and I drew his hand on my shoulder, like he was proud of me,” Enos says. The Disney CEO mailed back a package thick with information on the studio’s productions, a dream come true for Enos, who thought everyone must be writing Eisner to line up future employment.

When not pitching his talents to animation bigwigs, Enos spent his childhood and teen years visiting Oakland’s Children’s Fairyland, working on hot rods and drawing. He studied at both the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and the San Francisco Art Institute, getting his MFA from UC Berkeley in 2015. His influences tend toward a certain kind of fantastic world-making: Disney and Warner Bros. animation, theme parks, roadside attractions and the Chicago Imagists.

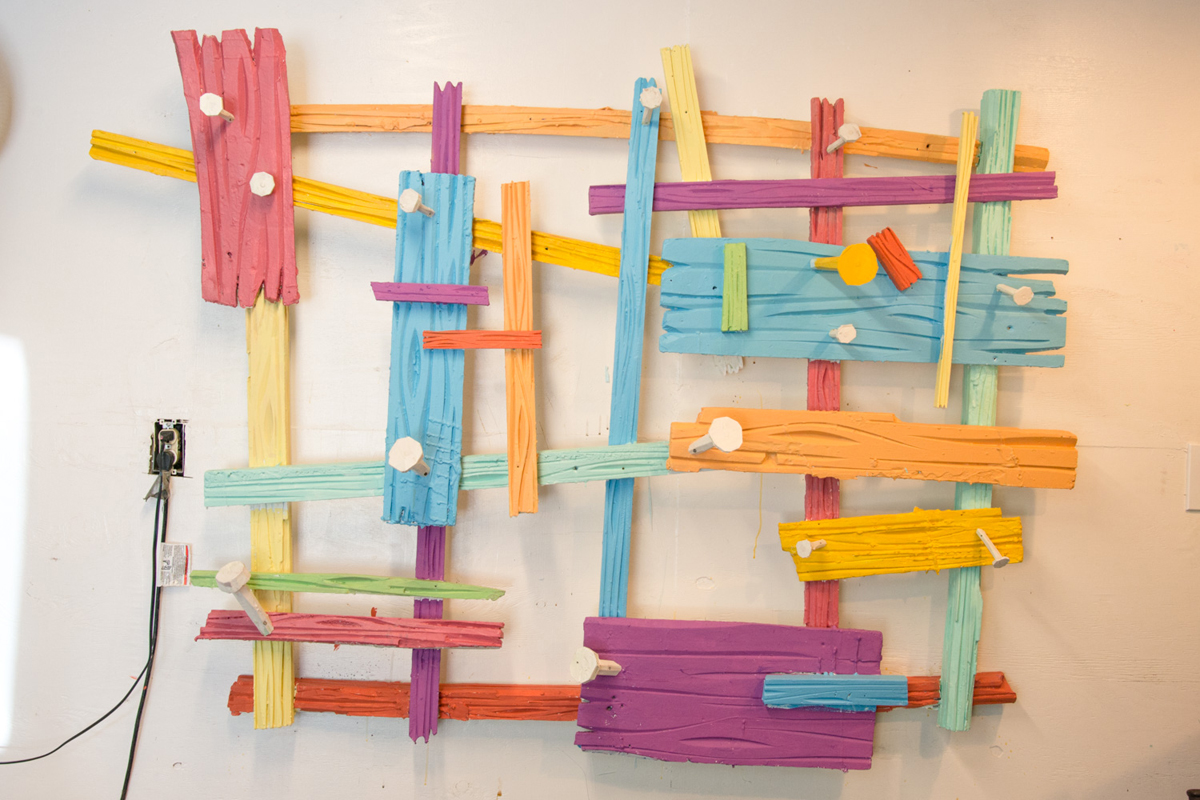

Enos makes his sculptures with simple materials — carved foam and layers of paint — to resemble column-like combinations of weathered planks, giant spikes, riveted sheets of metal and discarded tires. His art has an overexaggerated quality, like the clapboard architecture seen in Looney Tunes cartoons from the golden age of animation.

His outdoor sculptures are covered in a hardy Polyurea coating to protect their lightweight foam insides. Three recently weathered nearly a year at Paradise Ridge Winery outside of Santa Rosa, for the group exhibition Conversations in Sculpture. Those red, blue and yellow pieces, now returned, line the vegetable-turned-wildflower garden outside Enos’ home, towering over the neighbor’s fence.