Hepatitis C drugs are not the only part of California’s troubling drug spending picture. Despite recent cost-cutting measures, such as putting tighter controls on which patients get coverage for which drugs and when, California’s spending on pharmaceuticals has gone up, and so has the number of pricey drugs it is covering. It’s not clear state agencies have the means to balance drug cost pressures in a way that serves the best interests of patients, taxpayers and public health.

“There are very few tools in our toolbox” to control pharmaceutical spending, said Diana Dooley, secretary of California’s Health and Human Services. She says high prescription drug costs are a problem across California’s public and private health insurance, and should be addressed on a national level.

Drug price concerns will also be a matter of public policy debate this year. California voters are expected to decide in November on a measure to put a ceiling on what the state pays for drugs, and lawmakers have proposed drug price transparency requirements on pharmaceutical manufacturers and health insurers.

“We all have to do everything we can to try to control these drug costs,” Dooley said.

A CALmatters analysis found that state prisons, a California public pension system, and one subset of the Medi-Cal program spent $600 million more on pharmaceuticals in 2014 than in 2012. That does not include the Medi-Cal population in a health plan, nor does it account for discounts the state may have received from drugmakers.

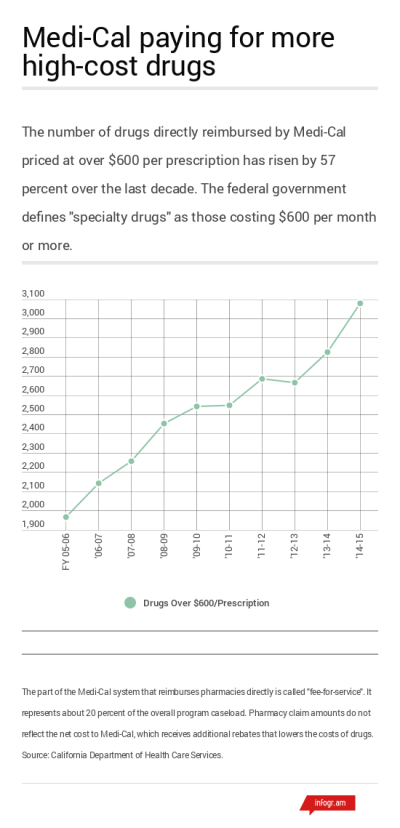

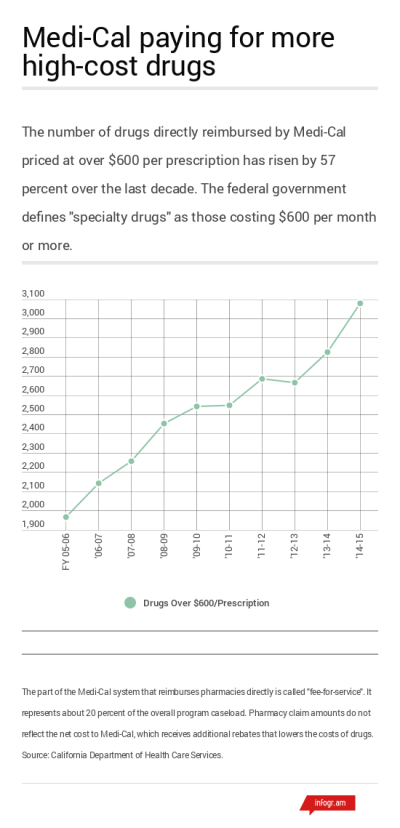

Over the past decade, Medi-Cal has seen a 57 percent increase in the drugs it covers that cost $600 or more per prescription. And when it comes to hepatitis C drugs alone, Medi-Cal estimates it will spend almost $482 million over this fiscal year and last. As of September 2015, only 4,200 Medi-Cal patients had received the drugs in that time period, out of 237,000 who are estimated to have the disease.

These cost trends exist despite new protocols various state agencies have introduced to tamp down on pharmaceutical spending, which include stricter controls on which patients get which prescription drugs and how.

“The people that pay for health care, be it the government or employers, are asking for more prior authorization because we’re having to scrutinize every penny we spend now,” said Steve Miller, chief medical officer at Express Scripts, which manages pharmacy benefits for health plans nationally, including 7.5 million Californians.

Miller said involvement from the payer is meant to get “the right patient, the right drug, at the right dose.” But the process, can be “clunky” and cause delays and frustrations for patients like Castillo.

Drugmakers say the value of the new hepatitis C drugs, the first of which hit the market at the end of 2013, is worth the cost, and in the long term, may eventually even bring savings to the health system.

The new hepatitis C drugs involve only a few months of treatment, and produce a cure in about 90 percent of patients. The older generation of treatments are cheaper, but are also about half as effective, and have side-effects that resemble the flu.

“These patients are now healthier. They’re more productive. They’re functioning,” said Priscilla VanderVeer, deputy vice president of communications at the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA).

“You’re going to have less people who need long-term medication therapy for their hep C, they’re not going to need liver transplants, they’re not going to need significant hospitalizations,” VanderVeer said.

Health consumer advocates and economists argue that paying a lot for some drugs that only treat a limited population may not serve larger public health interests, or be the best use of taxpayer dollars.

For example, if the cost of the new hepatitis C drugs were cheaper, the hundreds of millions of dollars spent on treating just a few thousand patients could have been spent to help eradicate the disease, says Anthony Wright, executive director of Health Access, an advocacy group.

“You could imagine a strategy to provide this cure in a much more broad population strategy,” Wright said.

Specialty drugs, which the federal government defines as costing $600 or more a month, are raising concern among health insurers and state agencies. In CalPERS, for instance, specialty drugs are taking up a larger share of total drug expenditures, despite the fact that they account for a small percentage of prescriptions.

Specialty drugs, which the federal government defines as costing $600 or more a month, are raising concern among health insurers and state agencies. In CalPERS, for instance, specialty drugs are taking up a larger share of total drug expenditures, despite the fact that they account for a small percentage of prescriptions.

Drugmakers are investing more in these types of drugs, said Joel Hay, a pharmaceutical economist at the University of Southern California, because “the profits are very high.”

But paying a high price for drugs that treat a small number of patients raises an equity question, Hay said. It may not be fair to the larger patient population for a health system to pay a high price for cancer drugs that extend a patient’s life by three weeks.

“You can get a lot more lives saved if you take that budget and put it into colon cancer screening or any number of other more efficient, more effective interventions,” Hay said.

The cost pressure from specialty drugs may not go away soon. Pharmaceutical benefits manager Express Scripts estimates that this class of drugs will continue to grow in Medicaid programs by 13.6 percent over the next three years.

“Are we going to have a sustainable (pharmaceutical) industry where we are making sure the drug companies make enough money where they can bring great new products to the marketplace, yet we control cost well enough that people –- all people, even the most vulnerable -- have access to the drugs they need?” asked Miller.

State Medi-Cal administrators say it’s too soon to assess the sustainability of current prescription drug spending trends. Meantime, their guidelines about which patients can get covered by new hepatitis C drugs has recently loosened up. As of July 2015, patients with a less advanced stage of liver disease can get covered for the drugs, as well as IV drug users and women who want to get pregnant.

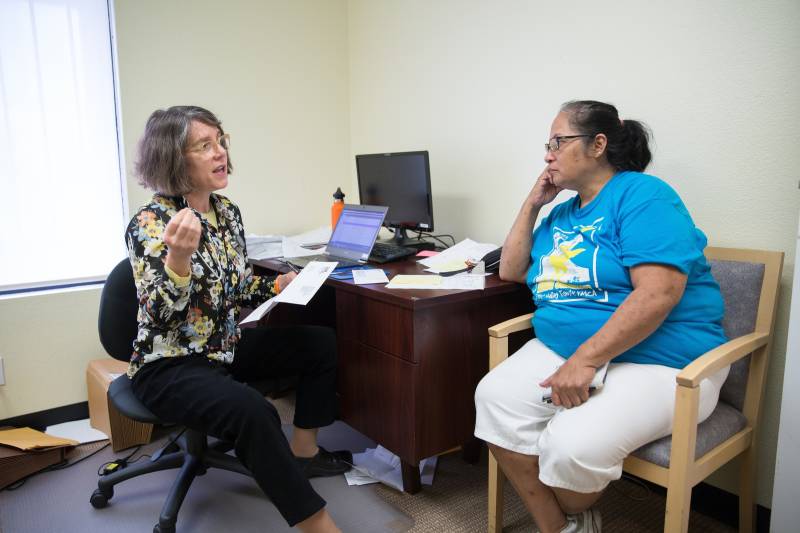

Castillo got her medication in March, after an attorney helped her challenge denied coverage for Sovaldi through a health insurance regulator. Castillo says she’s glad she’s in treatment now, but she doesn’t know why her Medi-Cal health plan made it so hard for her to get the medicine.

“They need to get it together,” she said. “It’s our health and our life that they’re messing with.”

Specialty drugs, which the federal government defines as costing $600 or more a month, are raising concern among health insurers and state agencies. In CalPERS, for instance, specialty drugs are taking up a larger share of total drug expenditures, despite the fact that they account for a small percentage of prescriptions.

Specialty drugs, which the federal government defines as costing $600 or more a month, are raising concern among health insurers and state agencies. In CalPERS, for instance, specialty drugs are taking up a larger share of total drug expenditures, despite the fact that they account for a small percentage of prescriptions.