Editor's note: California’s farmworkers face a litany of health hazards on the job: working bent over and carrying heavy loads of produce is hard on the back, hips, and knees; long hours in the sun can mean heat exhaustion, or worse. Employers don’t always provide the state-mandated access to shade, drinking water, and restrooms. The state’s regulatory agencies can’t keep a very close eye on such a large area.

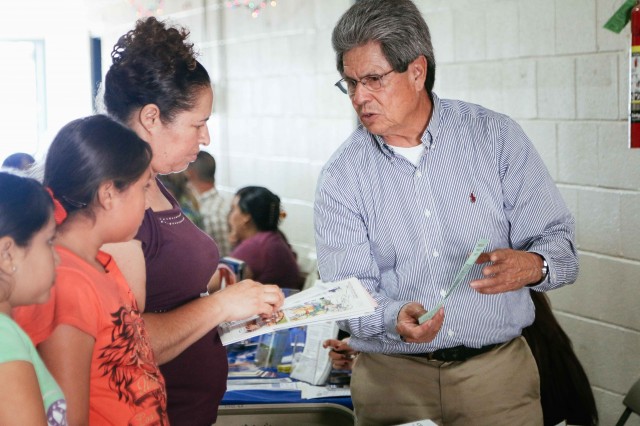

To help fill this gap in enforcement, community health worker Ephrain Camacho drives the back roads with a pair of binoculars, pulling over wherever he sees a crew of workers to make sure they have the workplace protections they’re entitled to. As part of our community health series Vital Signs, we followed him to a health fair near Fresno to learn more about his work and about farmworker health.

By Ephraim Camacho

We call it 'reading the land.' You park on the side of the road and observe. The first thing we look for is the porta-potties, drinking water, and the shade.

If we see that there are not enough toilets, or that they’re lacking drinking water, or even drinking cups, we enter the field and talk to the employer about voluntary compliance.