In this study, instead of starting women on hormones, as the Women's Health Initiative study did, the Stanford researchers recruited women already taking them and then randomized them into two groups -- some would continue taking hormones, some would stop.

"They start women on hormones, and we stopped women on hormones. Biologically it's a very different phenomenon," said Dr. Natalie Rasgon, director of the Stanford Center for Neuroscience in Women's Health, lead author of the study.

Rasgon and her team also recruited significantly younger women, ages 50-65. The researchers measured metabolic activity in specific brain regions associated with memory and executive function, using sophisticated PET scans. Rasgon said that studies have shown that these areas can show a decline before a person would notice symptoms of Alzheimer's disease.

One Type of Estrogen Helps, Another Doesn't

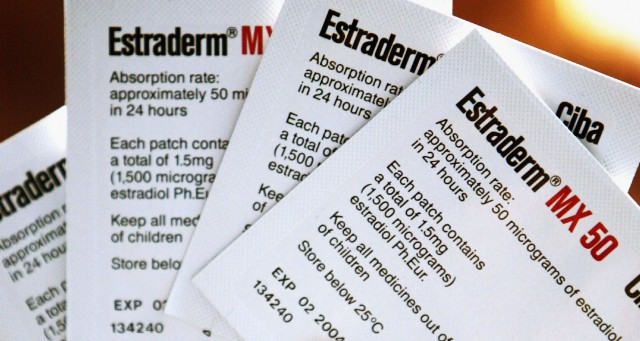

They found that women taking a type of synthetic estrogen called estradiol saw that their brain function was better preserved. But here's the rub: Another kind of estrogen, conjugated equine estrogen, often known by the brand name Premarin, did not confer the same benefit. The study found that women who took Premarin saw a decline in the key brain regions studied. Results were published in Plos One.

Many women who take hormone therapy take both synthetic estrogen and progesterone, in part because estrogen therapy alone increases a woman's risk of uterine cancer. In women in the study who took both hormones, the synthetic progesterone wiped out any benefits provided by estradiol and increased the brain decline seen in women taking Premarin.

"It's a very provocative finding, without a doubt," Rasgon said.

Estradiol is a "synthetic molecule which exactly mimics the estrogen produced by the ovary," Rasgon said. Pfizer, which manufactures Premarin, describes it as "a mixture of conjugated estrogens obtained exclusively from natural sources."

Before you rush out to take estradiol to help ward off Alzheimer's disease, Rasgon was careful to issue clear caveats. First, this is a small study, just 45 women, "and it's a very specific population," she said. "It's a population that is at risk for Azheimer's disease."

In order to be included in the study, women were required to be at increased risk for dementia, as indicated by having a first-degree relative with Alzheimer's disease, or that they were known to carry a specific variant of the ApoE gene, which is associated with increased risk of Alzheimer's. Women who had a personal history of major depression were also eligible.

In the PET scans, researchers were looking only at changes in metabolic activity in the brain -- a marker for brain preservation -- and not at direct cognition among the women. "Metabolic changes in these brain regions presage overt symptoms of cognitive decline, sometimes by decades," Rasgon said. "We're finding significant changes in women who are still cognitively intact."

"This is a wonderful study," said Dr. David Rubinow, former head of the division of behavioral endocrinology at the National Institute of Mental Health and now at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill. He was not involved in the study. "Dr. Rasgon was able to demonstrate that there were marked differences between conjugated equine estrogen and estradiol, and both of those observations had been suggested but were untested."

Rubinow said that more study is needed. "Is this a study that suggests that we need to redouble our efforts to determine the effects of estradiol administered during perimenopause on cognitive function? The answer is yes."

Lack of Randomization Raises Questions

Dr. Rita Redberg, director of Women's Cardiovascular Services at UC San Francisco, was more skeptical. While changes in metabolic activity in the brain are a marker for disease, "a marker is a long way from dementia," she noted. While people who now have Alzheimer's disease may well have started off with these changes years ago, it's likely that many people will experience these metabolic changes but never go on to develop dementia.

Redberg also was concerned that women came into the study already taking hormones. The study required that women already be taking them for at least one year, so this means the women were not randomly assigned estradiol or Premarin. "There were likely differences among women who chose to take estradiol and women who chose to take (Premarin), so it wasn't randomized."

Women can slow or prevent memory loss by eating a healthy diet and getting regular exercise, Redberg said. Also, estrogen therapy increases a woman's risk for breast cancer.

Rasgon agreed that diet and exercise can help people reduce their risk of dementia, but she also stressed that women should assess risks and benefits of hormone therapy individually. "Those risks and benefits have to be accounted for now for the type of hormone preparation they are taking and presence or absence of progestin," she said. "Not every women taking progestin may need it. … Those factors were not part of the equation in the past and now they should be -- at least for those who are at risk for Alzheimer's disease."